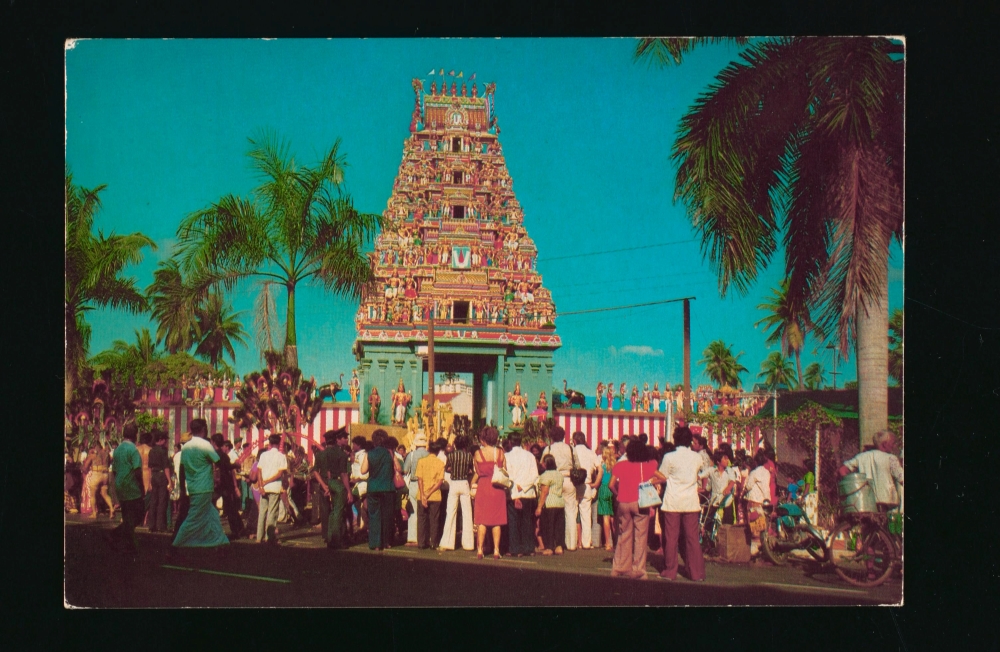

Silver Chariot Procession

The Silver Chariot Procession (Tamil: வெள்ளி தேரி ஊர்வலம்) is a religious ritual practiced during Hindu festivals and auspicious consecration ceremonies.

In Singapore, a huge processional cart carrying an image or idol of the festival’s presiding deity, known as the utsuva marti (Sanskrit: उत्सव मूर्ति), is towed along a public route by worshippers. The craftsmanship and maintenance of silver chariots before and after the procession are an integral part of the tradition. The practice is associated with “temple chariots” or kovil thers (Tamil: கோவில் தேர்), dating back to India in the second century BC. Spoke-wheeled chariots ridden by gods and kings appear often in Indian mythology.

In 19th century Singapore, Indian migrants who worshipped at Hindu temples organised chariot processions, amongst other religious rituals. The practice has become more common in Singapore as Hindu temples grew in number.

The processions may vary across temples, as the temples celebrate different festivals and gods, although they serve similar purpose of pleasing the presiding deity and letting public spectators receive divine blessings.

Geographic Location

The routes of different processions vary. For the Panguni Uthiram (occurs in the Tamil month of Panguni during the full-moon day) procession, the two organisers, Sree Maha Mariamman Temple and Holy Tree Sri Balasubramaniar Temple, use their temple grounds as the start and end points. Stopovers take place within the communal spaces in Yishun’s Housing & Development Board (HDB) estate. For the Punar Pusam (eve of Thaipusam) procession organised by Sri Thendayuthapani Temple and Sri Srinivasa Perumal Temple, stopovers are made at numerous Indian banks on Market Street.

Communities Involved

Communities involved include the priests, devotees and volunteers of all ages at the numerous Hindu temples across Singapore, who participate in the Silver Chariot Procession.

Associated Social and Cultural Practices

Parts for the chariots are sculpted and constructed in India, then shipped to Hindu temples in Singapore to be assembled. Prior to the chariot’s departure, priests lead a special puja (Devanagari: पूजा, pūjā), a devotional worshipping session. Hindu volunteers then carry the utsuva marti out of the temple and lift it onto the silver chariot waiting on the road outside. It is placed on the kavadul ukarumidam (“resting seat of God”), and priests conduct aarti (Devanagari: आरती, “Act of Waving of Lights”) before the chariot sets off.

Devotees walking alongside the chariot experience darsana (Sanskrit: दर्शन), an auspicious sighting of the deity. These sightings also occur when they approach the chariot during its stopovers to offer the deity varisai, plates of offerings.

Even when the chariot reaches its destination, the procession is not complete until the utsava murti is restored back to the sanctum in its original state, and the deity must be appeased through rituals of cleaning and purification that may take days.

In 19th century Singapore, these chariots were wooden and towed by bullocks. Today, motor vehicles, rather than a sacred pair of bullocks, are used to tow the chariot.

As Hindu temples grow in proximity to one another, they increasingly collaborate during festivals and have used other temples as stopping points.

Experience of a Practitioner

Mr Ramasamy and Mr Annamalai have held leadership positions in the management committee of the Chettiars’ Temple Society. In explaining their involvement in temple management, Mr Ramasamy and Mr Annamalai point to their family lineage as Nattukottai Chettiars. Nattukottai Chettiars were originally money-lending officers from India, living and conducting business in kittangi, complexes comprising living quarters and offices. They each take a year’s term as the management committee for the Chettiars’ Temple Society. This tradition is a legacy left by the first-generation Chettiars. Overseeing the Silver Chariot Procession is thus one of the many responsibilities they have.

According to them, volunteers are heavily involved across various stages of the procession. About 15 – 20 volunteers polish and maintain the chariot beforehand, and it is also the “big bulk” of volunteers that is crucial on the day of the procession. They added that volunteers are responsible for food serving, preparations, and sanctums, and help manage the large crowds of people that come and go throughout the day.

Present Status

Little threat exists to the sustainability of Singapore’s silver chariot processions, says Mr Ramasamy and Mr Annamalai. Devotees from all age groups continue to participate in such Hindu religious traditions.

One challenge for them, however, is that younger generations may grow out of touch with aspects of their cultural and religious heritage. To address this, classes covering these topics have been held—an initiative by the temple to ensure that future generations remain open and receptive to the religious festivals and practices, and will eventually take on the leadership roles associated with Nattukotai Chettiars.

References

Reference No.: ICH- 056

Date of Inclusion: March 2019

References

Belle, Carl Vedivella. Thaipusam in Malaysia: A Hindu Festival in the Tamil Diaspora. Singapore: ISEAS Publishing, 2017.

Chettiars’ Temple Society. The Golden Memories. Singapore: Gemini Graphics & Printers Pte Ltd, 2016.

Johnson, W. J. A Dictionary of Hinduism. Oxford University Press, 2009.

Kesari, Vedanta. Living Imprints of Indian Culture: Some Glimpses of the Indian Cultural Practices (eBook). Chennai: Sri Ramakrishna, 2014.

Kong, Lily. “Mapping ‘new’ geographies of religion: politics and poetics in modernity’, Progressing Human Geography, 25 (2): 211-233, 2005.

Krishna, Nanditha. Arts and Crafts of Tamil Nadu (Living Traditions of India). Ahmedabad: Grantha Corporation, 1992.

Lochtefeld, James. The Illustrated Encyclopedia of Hinduism: A-M. New York: The Rosen Publishing Group, 2002.

Sinha, Vineeta. “Gods on the move: Hindu chariot processions in Singapore.” In Jacobsen Knut (ed), South Asian Religions on Display: Religious Processions in South Asia and the Diaspora. London: Routledge, 2008.

Vemsani, Lavanya. Krishna in History, Thought, and Culture: An Encyclopaedia of the Hindu Lord of Many Names. Santa Barbara: ABC-CLIO, 2016.