Mid-Autumn Festival

The Mid-Autumn Festival, or the Mooncake Festival as it is commonly known in Singapore, is celebrated by Chinese communities all around the world. It falls on the 15th day of the eighth month of the Chinese Lunar Calendar, when the moon is believed to be at its fullest. The festival is a time for families to bond together while consuming mooncakes, pomelos, and tea, while children often play with lanterns.

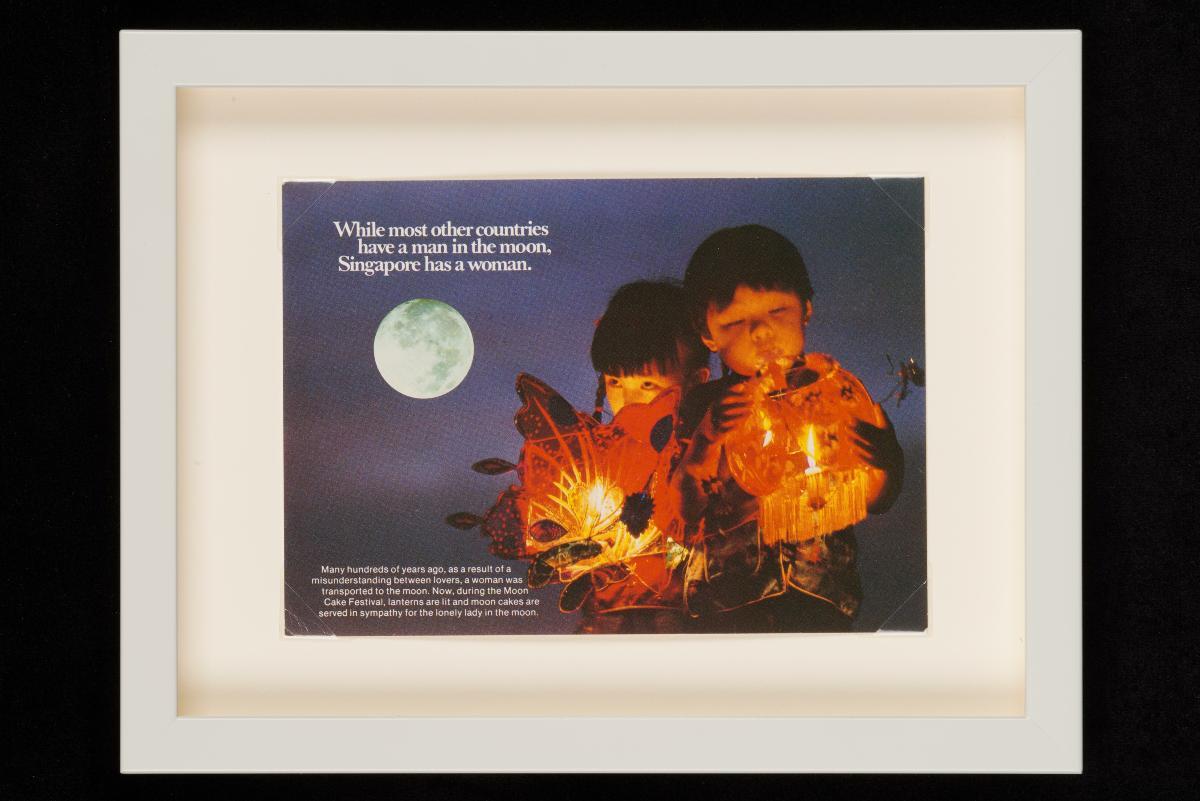

The Mid-Autumn Festival is likely to have origins in ancient worship practices of the moon, and served as a harvest festival to express gratitude to the gods. There are many myths surrounding the origins of the Mid-Autumn Festival, and the most common one is the story of Chang E (嫦娥), the wife of Hou Yi (后羿). Several versions of this myth exists, and in a commonly cited version, she drinks the elixir of immortality to save her people from the eternal tyranny of an immortal Hou Yi, who had become an arrogant and domineering ruler. When Chang E drank the elixir, she found herself transported to the heavens. Chang E has been traditionally worshipped by the Chinese community as the Moon Goddess. Other myths associated with the festival include the pounding of medicine by the Jade Rabbit (玉兔捣药) and Wu Gang, the woodcutter (吴刚伐桂).

The festival is also linked to the war between the Han Chinese resistance army and the Yuan Dynasty in the mid-14th century. According to folklore, the rebellion used mooncakes to hide messages that called for an uprising on the night of mid-autumn.

Geographic Location

The Mid-Autumn Festival is celebrated in various parts of the world where there are Chinese communities.

In Singapore, celebrations take place in clan associations and community centres which hold activities during the Mid-Autumn Festival, as well as in spaces within neighbourhoods and households.

Communities Involved

The Mid-Autumn Festival is widely celebrated across Singapore mainly by the Chinese community, and increasingly across other ethnicities. Families, schools, Chinese clan associations, and multi-ethnic workplace communities often partake in these celebrations.

Associated Social and Cultural Practices

Celebrations for this festival involves social gatherings and an opportunity to indulge in mooncakes.

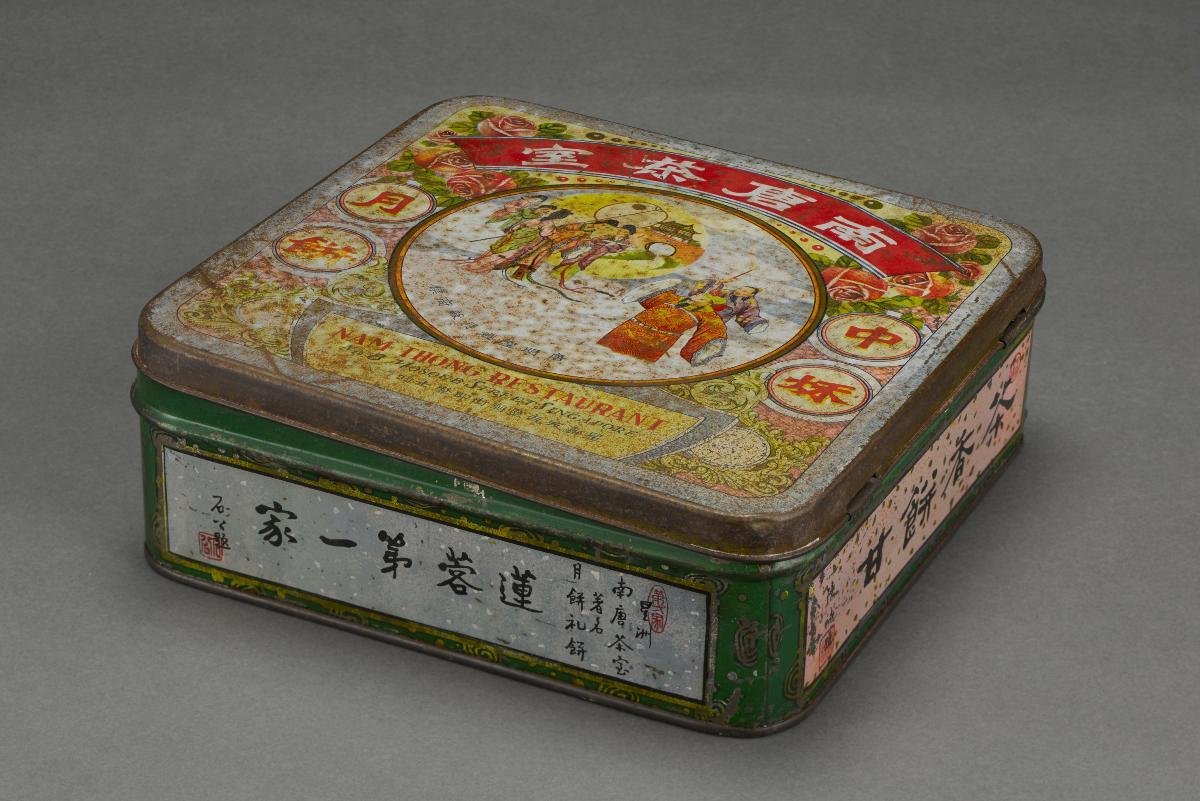

The mooncake—a hallmark of the festival—is a round pastry traditionally filled with lotus-seed or bean paste and salted egg yolk. Its circular shape signifies domestic harmony and the fullness of the moon. Non-traditional mooncakes include the “snow skin” mooncakes and new flavours or forms, which may include ice-cream, chocolate and other sweet fillings. They are packaged and eaten like desserts.

It is common for mooncakes to be exchanged as gifts between businesses and clients, employers and employees, and family and friends. This exchange symbolises respect and esteem.

Another hallmark of the festival is the lighting and carrying of lanterns. These lanterns were originally used as spiritual offerings in the past. On the night of the festival, children are often seen carrying lanterns of all shapes and sizes in and around their housing estates, against the backdrop of the full moon in the night sky.

Experience of a Practitioner

One person who has fond memories of Mid-Autumn Festivals is Madam Au Yue Pak. Madam Au is an elder and council member of the Kong Chow Wui Koon Clan Association. The Association organises celebratory gatherings for members during the Mid-Autumn Festival, and shares the associated traditional beliefs and practices with the younger generation. As a child, Madam Au and her family prayed to the Moon Goddess and lit a single lantern with a candle on the day of the festival. Offerings included incense, tea or wine, mooncakes, pomelos, yams, and melons. The family would cook bee hoon (a type of noodles) for dinner before indulging in mooncakes for supper.

While the celebratory element of the festival remains strong, the traditional theme of harmony and home does not feature as strongly for younger Singaporeans. Elders like Madam Au have observed a waning interest in the festival’s traditional practices, songs, folklore, and history among the youth. She feels that many people now practise only the custom of consuming mooncakes and tea.

Present Status

Every year, an increasing variety of mooncake flavours and lantern designs—even featuring popular cartoon superheroes and video game characters—are available to attract a growing demographic beyond the Chinese community. Madam Au welcomes such innovations, and considers them helpful in keeping the traditions of the Mid-Autumn Festival relevant in an ever-changing society.

There has also been a renewed emphasis in local schools on teaching and learning about local cultural diversity, where teachers are helping students to appreciate the significance of popular celebrations such as the Mid-Autumn Festival. The festival remains widely celebrated by families as a time of reunion and celebration, and is likely to remain an important practice among the Chinese community in Singapore.

References

Reference No.: ICH-025

Date of Inclusion: April 2018; Updated March 2019

References

Cai Shenshen. “The Cultural Representation and Politics of the Chinese Moon Festival Gala: Nationalism, Nostalgia and Romance.” East Asia, 31: 249–267, 2014.

Chao Wei-Pang. “Games at the Mid-Autumn Festival in Kuangtung.” Folklore Studies, 3 (1): 1-16, 1944.

Cheong Suk-Wai. “A taste for every tongue.” The Straits Times, 12 September 1999.

Chia, Felix. The Babas. Singapore: Estate of Felix Chia Thian Hoe and Landmark Books, 2015.

Fang Xiao. “The Predicament, Revitalization, and Future of Traditional Chinese Festivals.” Western Folklore, 76 (2): 181-196, 2017.

Gai Guoliang. Exploring Traditional Chinese Festivals in China. Singapore: McGraw-Hill Education (Asia), 2009.

Huang Lijie. “A hit: Snowy mooncakes.” The Straits Times, 21 September 2009.

James, Josephine. “Lantern making sheds light on festival.” The Straits Times, 11 September 2000.

Lim, Mary. “Magic in the moonlight.” The Straits Times, 28 August 2008.

Singapore Federation of Chinese Clan Associations. Chinese Customs and Festivals in Singapore. Singapore: Singapore Federation of Chinese Clan Associations, 1989.

Siu, Michael Kin Wai. “Lanterns of the Mid-Autumn Festival: A reflection of Hong Kong cultural change.” Journal of Popular Culture, 33 (2): 67-86, 1999.

Stafford, Charles. Separation and Reunion in Modern China. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2000.

Tham Seong Chee. Religion and Modernisation: A Study of of Changing Rituals Among Singapore’s Chinese, Malays & Indians. Singapore: Graham Brash, 1985.

Wei Liming. Chinese Festivals. New York: Cambridge University Press, 2011.

Yang Lemei. “China’s Mid-Autumn Day.” Journal of Folklore Research, 43 (3): 263-270, 2006.

Zhang Zhiyuan. “A Brief Account of Traditional Chinese Festival Customs.” Journal of Popular Culture, 27 (2): 13-24, 1993.