Making of Tempeh and Tapai

Tempeh and tapai are fermented food commonly produced and consumed in Southeast Asia, particularly in Indonesia, Malaysia and Singapore. In Singapore, soya beans are the main ingredient in making tempeh. Tapai, on the other hand, are fermented rice cakes made from cassava or rice. The mycelium culture used for the fermentation process gives tempeh and tapai its unique flavour.

Geographic Location

Both tempeh and tapai are thought to have originated in Java. There are several variations of tempeh and tapai made from different legumes and ingredients in Indonesia. For instance, velvet beans and soya bean curd residue are used to make tempeh benguk and tempeh gembus respectively. However, the soya bean-based tempeh is the most common type in Singapore.

Communities Involved

Historically, early tempeh makers and sellers in Singapore were usually of Javanese ancestry. There used to be many tempeh makers living in Geylang Serai, Kampong Gelam, and areas around Bukit Timah. Of particular interest is Kampong Tempeh, a large village spread across Jalan Haji Alias, Jalan Lim Tai See, Coronation Road West, Jalan Siantan, Jalan Ampang and Jalan Tuah (now expunged). Villagers harvested rainwater, which was regarded as ideal for tempeh making. Children helped to peel tapioca skins and spread ragi (yeast starter) over them. In its heyday, Kampong Tempeh was said to produce over 5,000 pieces of tempeh daily. Peddlers were then deployed to sell the tempeh across the island. By the 1980s, most of the residents of Kampong Tempeh were relocated, and the once flourishing tempeh- and tapai-making cottage industry went into decline.

Today, while tempeh and tapai are primarily manufactured in factories and distributed to market stalls selling other soy-based products, there are also individuals who make their own at home.

Associated Social and Cultural Practices

Different ingredients are combined and fermented with ragi (yeast starter) to make tempeh and tapai. To prepare ragi, rice flour is mixed with small amounts of pepper, sugar, garlic, ginger, galangal, key lime, and other spices; all these ingredients contain natural yeast required for fermentation to occur. Water is added to the mixture to form a thick paste, which is then shaped into small cakes. The ragi cakes are left on trays at room temperature for approximately two to five days before they are sun-dried.

One of the ways to make tempeh begins with the boiling of soya beans, which are left to soak in the water overnight in room temperature to promote bacterial acid fermentation. The soya beans are then boiled a second time, drained, and left to cool overnight. They are dehulled and boiled for the last time before they are spread out on a wooden platform to dry. Then, they are coated with ragi to inoculate them with mycelium. Finally, the soya beans and ragi mix is wrapped in either banana or simpoh air (Dillenia suffruiticosa) leaves to ferment for up to 48 hours. Dense white mycelium covers and binds the soya beans tightly during this process. They are later rewrapped in new leaves and secured with strings.

Freshly made tempeh is meaty and has an earthy smell; it is sometimes used as a meat replacement. It is a versatile food product and can be served in various ways, whether fried, baked or added to soups. Locally, tempeh is usually deep-fried and enjoyed with rice, vegetables and sambal goreng (stir-fry mix of long beans, tempeh and beancurd).

To make tapai, glutinous rice is steamed and cooled before ragi is stirred in. The mixture is poured into a bowl or wrapped in banana leaves to ferment at room temperature for up to three days. Over time, it develops into a paste that can either be used as an ingredient for other dishes or consumed as a sweet snack with a fermented taste known as tapai pulut.

Another variant of tapai is known as tapai ubi in Singapore (or tapai singkong in Java). Mainly made from cassava, fresh young roots are peeled and cooked until tender before they are covered with ragi. Placed in a criss-cross fashion in wooden baskets or wrapped in banana leaves, the inoculated cassava roots are left to ferment. The result is a sweet tapai ubi with a slight fermented taste.

Experience of a Practitioner

Mdm Asiah bte Omar recalls watching her father make soya bean tempeh, tapai pulut and tapai ubi as a child. Presently, she owns Berkah Stall located at Tekka Centre, where she prepares and sells her own tapai. She has made some adjustments to the traditional method of making tapai, including sieving ragi before use and adding sugar to sweeten her tapai. While some stalls have switched to using plastic bags and containers, Mdm Asiah has insisted on using banana leaves to wrap and package her tapai for sale. She believes that it is crucial to pass down traditional methods of preparing food, although she recognises that not many in the younger generation would be keen to learn them.

Present Status

In Singapore, tempeh and tapai represents the culinary heritage of the Javanese community. Even though home-based tempeh and tapai making is increasingly uncommon these days, they are still produced commercially and sold in markets today. Many Malay and Peranakan food establishments also offer tempeh and tapai dishes on their menus. Furthermore, tempeh is enjoying an increased popularity in recent years as a health food and meat substitute in vegetarian and vegan dishes.

References

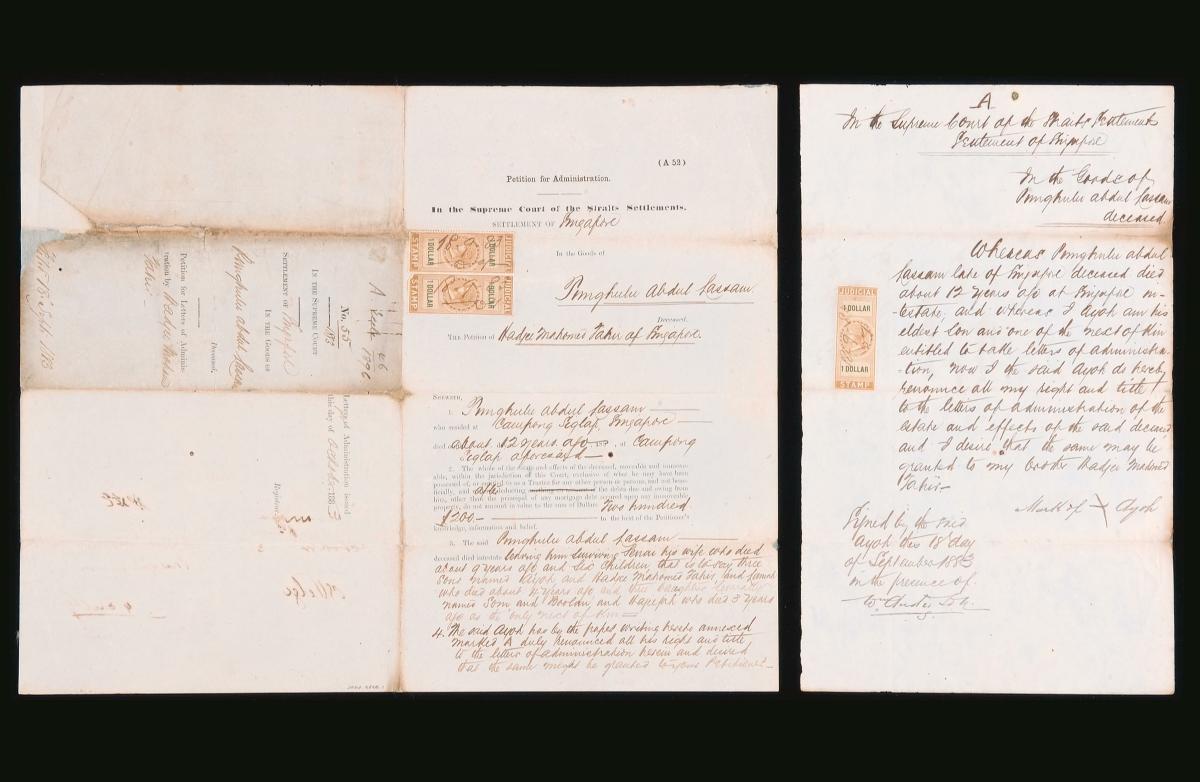

Reference No.: ICH- 097

Date of Inclusion: November 2020

References

Anonymous. ‘Kampong Tempe’. Al-Huda Mosque. n.d. http://www.alhuda.sg/kampongtempe.html. Accessed 28 July 2017.

Mahori, Mokson. ‘Education in Singapore’. Oral History Centre. Accession Number 002622, Reel / Disc 4 of 27. 1 March 2002. http://www.nas.gov.sg/archivesonline/oral_history_interviews/record-details/a0a258a6-115e-11e3-83d5-0050568939ad?keywords=Mokson&keywords-type=all. Accessed 28 July 2017.

Sanusi, Yahaya, and Hidayah Amin. Kampung Tempe. Singapore: Helang Books, 2016.

Shurtleff, William, and Akiko Aoyagi. The Book of Tempe. Lafayette: Soyinfo Center, 1979.

Wang, H. L., and C. W. Hesseltine. ‘Glossary of Indigenous Fermented Foods’. Mycologia Memoir, no. 11 (18) (1986): 317–344.