Making of Chinese Signboards

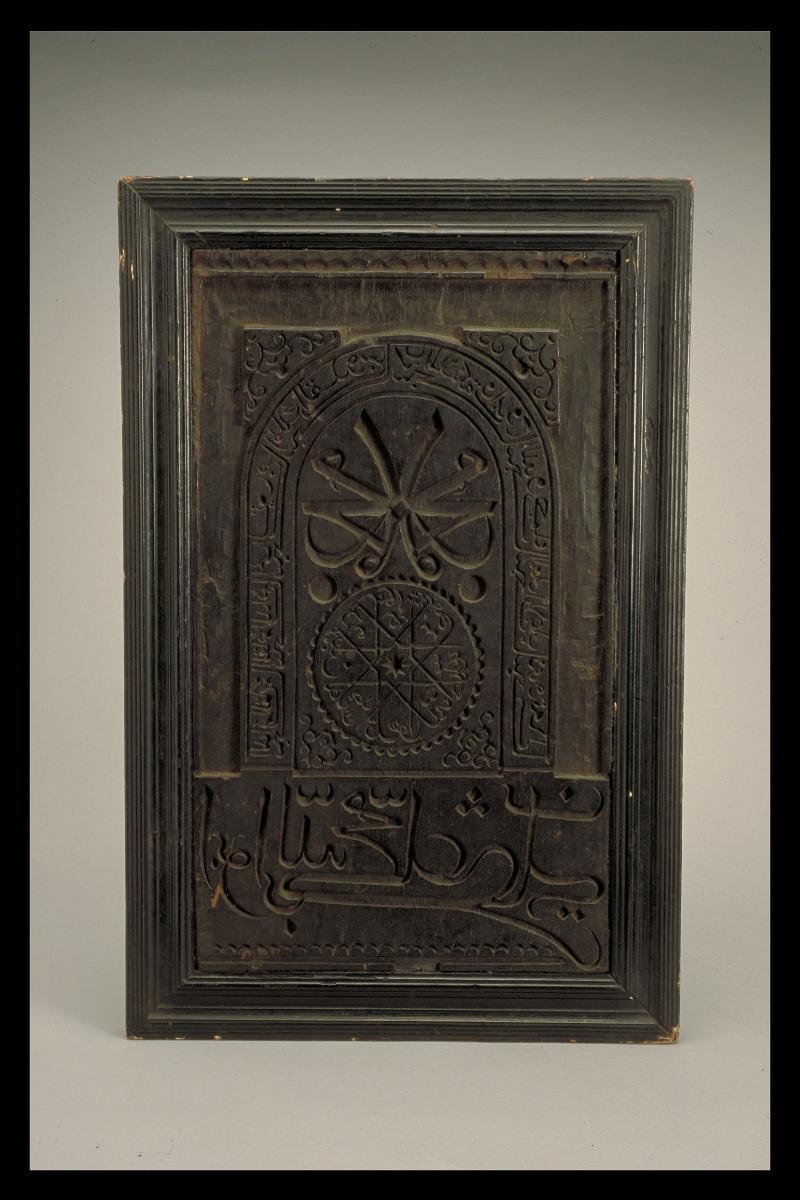

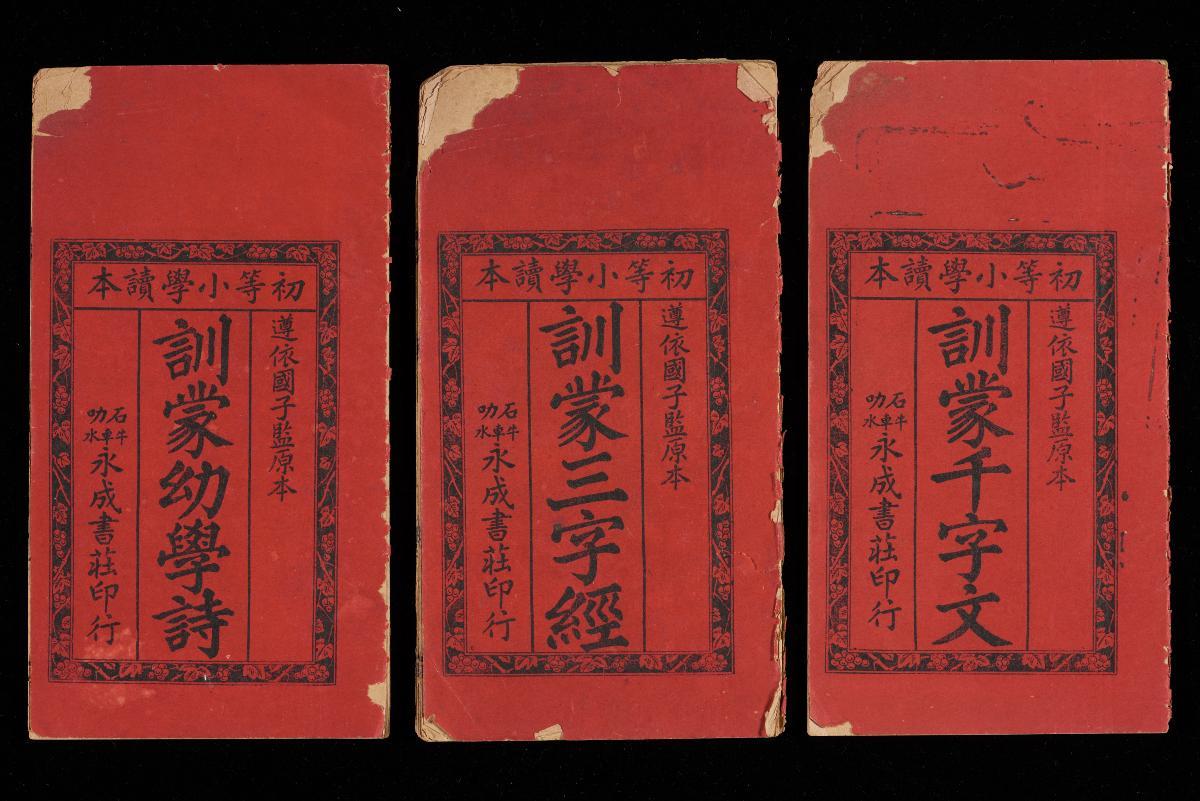

Traditionally, signboards are hung above the entrances and doors of Chinese temples, clan associations, businesses, schools and even private homes. Usually made with wooden boards, these plaques are either carved or painted with beautiful calligraphic characters that indicate the name and use of the building or space.

Skilled Chinese migrants brought with them the ancient craft of signboard making when they left China for Singapore in the 19th century. In the 1960s, most traditional signboard makers were found on Pekin Street (presently a glass-covered walkway), a thoroughfare connecting China Street and Telok Ayer Street where woodworkers and carpenters once congregated. By the 1990s, the number of signboard makers in Singapore had dwindled to just a handful. Today, only one traditional signboard maker remains active in Singapore.

Geographic Location

Signboards carvers could be found wherever there were sizeable Chinese communities. These included China, Malaysia and Singapore. Historically, Japan and Korea also boasted many signboard makers, as similar signboards carved with Chinese characters (kanji in Japanese and hanja in Korean) were also commonly used in these countries.

In Singapore, Yong Gallery is the only remaining traditional signboard maker.

Communities Involved

As a well-made signboard is believed to usher in good luck, many Chinese shop owners and merchants in early Singapore were eager to commission signboards for their storefronts. The Chinese also adorn the entrances of temples, clan associations, schools and even private homes with these plaques. For clan associations, the signboards further pay tribute to the benefactors and highlight the achievements of its members.

The craft of signboard making is closely tied to Chinese calligraphy. Renowned calligraphers were often invited to write the characters to be carved or painted on the signboards. For instance, the calligraphy of the master Xu Yun Zhi is immortalised on the signboards at Haw Par Villa and Singapore Khoh Clan Association.

Associated Social and Cultural Practices

In the past, demand for signboards soared between the 8th and 12th months of the lunar calendar because of the numerous auspicious dates for the opening of businesses during this period. A hand-carved Chinese signboard takes approximately two to three weeks to make. Firstly, the wooden board – commonly from the camphor tree – is measured and cut. A Lu Ban chi (ruler), which provides special measurements indicating the auspicious length for making a signboard, is traditionally used. The panel is then smoothened, soaked in water and air dried to ensure that it can withstand different weather conditions for a long time when it is hung outdoors.

When characters are to be carved on the wooden panel, a calligrapher is first enlisted to write the characters on a piece of paper as a template for the signboard maker to work on. The characters can either be carved using the ‘concave method’ (ao zi xing 凹字型), which entails simply chiselling away the width and depth of the characters’ strokes, or the ‘concave-and-convex method’ (ao tu xing 凹凸型). The latter technique is more complex, but it produces characters that are more multi-dimensional. After a final sanding, the signboard maker paints the panel black and either applies gold paint to the characters or gilds them with gold leaves.

Another method for making signboards comprises the application of paint directly onto metal plates. Usually coated in yellow or white paint, the metal plate is framed with wood. The signboard maker cuts out the Chinese characters written by a calligrapher on paper, then positions and traces them on the metal plate. To complete the signboard, the outlines of the characters are filled in with blue or red paint.

Bilingual or multilingual signboards can also be found in Singapore. Besides the Chinese characters, English and other languages are occasionally added to the signboards to make them intelligible to non-Chinese communities. While the Chinese characters on older signboards are usually read from right to left, those on some modern signboards are arranged to be read from left to right. Newer signboards also feature different colours, character fonts and alignments to make them more unique and conspicuous.

Experience of a Practitioner

Mr Cheh Kai Hon started woodcarving in the 1980s. Under the tutelage of the renowned Japanese calligraphy carver Mr Ajiro Chotei and local calligraphy master Mr Yong Cheong Thye, he learnt the aesthetics, spirit and mentality of the calligrapher when making signboards. As he honed his signboard carving techniques, Mr Cheh concurrently picked up calligraphy to better appreciate the beauty of Chinese characters. This, he believed, would help him become a better signboard maker.

In 1986, he partnered with Mr Yong to found Yong Gallery, the only active traditional signboard maker left in Singapore. Unlike paper, signboards can withstand the test of time. For this reason, Mr Cheh also sees signboards as records of important events in the history of Singapore as well as tributes to the works of famous calligraphers.

Present Status

Various reasons, including the lack of successors to the craft, lower demand due to changes in consumers’ taste and availability of machine-made signboards have led to the decline of traditional signboard making over the years. Today, Yong Gallery only receives approximately 10 requests per year to make signboards.

References

Reference No.: ICH-092

Date of Inclusion:November 2020

References

Baskin, Bernie. ‘The Last Signboard Maker in Penang’. The HUNT (blog). 5 February 2013. Accessed 13 August 2019. https://thehuntguides.tumblr.com/post/42335295772/the-last-signboard-maker-in-penang/amp.

Li, Chun Pu. 牌匾, 名人, 书法, 历史 (Signboards, Famous People, Calligraphy, History). Beijing: Zuo Lin You She, 2006.

Lim, Carl. ‘They Take Pride in Signboards’. The Singapore Free Press, 29 September 1951. Accessed 11 September 2020. http://eresources.nlb.gov.sg/newspapers/Digitised/Article/freepress19510929-1.2.100.19.

Mo, Mei Yan. ‘招牌已招了千年的生意’ (‘Signboards Have Attracted Business for Thousands of Years’). Lianhe Zaobao. 17 November 1991, 54.

Mo, Mei Yan. ‘最后的雕刻招牌业’ (‘The Last Signboard-Carving Business’). Lianhe Zaobao. 5 July 1992, 36.

Pan, Guoju. 新加坡华社五十年 (50 Years of Singapore Chinese Society). Singapore: Ba Fang Wen Hua Chuang Zuo Shi, 2016.

Thulaja, Naidu Ratnala. ‘Pekin Street’. Infopedia. n.d. Accessed 24 August 2019. http://eresources.nlb.gov.sg/infopedia/articles/SIP_326_2004-12-15.html.

Tu, Bao Yuan. ‘招牌与招牌字’ (‘Signboards and Signboard Characters’). Lianhe Zaobao. 30 December 1990, 38.

Xie, Yan Yan. ‘寻找匾牌背后的故事’ (‘Searching for the Story behind Chinese Signboards’), Lianhe Zaobao. 27 January 2014. Reproduced in Singapore Calligraphy People. Accessed 13 August 2019. http://thecccentre.blogspot.com/2014/01/2014n.html.