Kway Chap

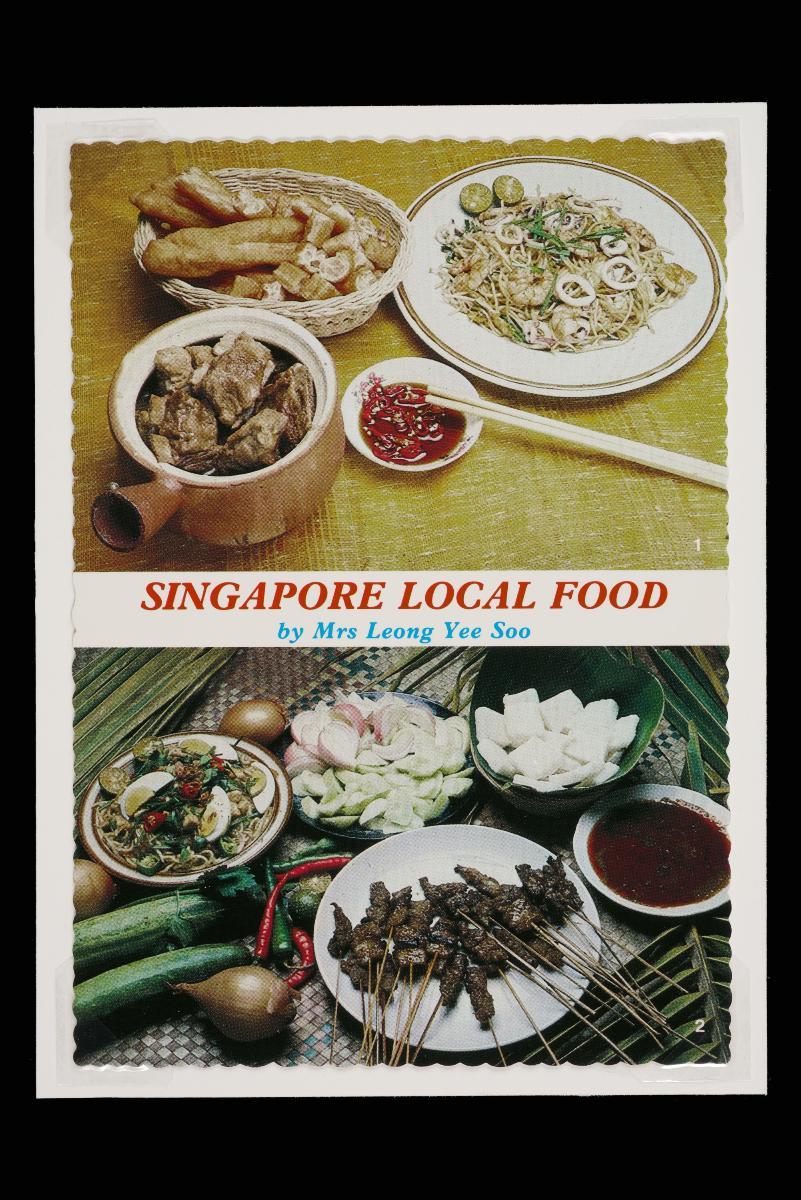

Kway chap 粿汁 is a dish of Teochew origin and was introduced to Singapore by early migrants from the Chaoshan region in China. The dish comprises broad sheets of rice noodles (kway 粿) served in a bowl of piping hot broth (chap 汁). It is usually enjoyed with an array of pork offal and other sides that are customisable to customers’ preferences.

Geographic Location

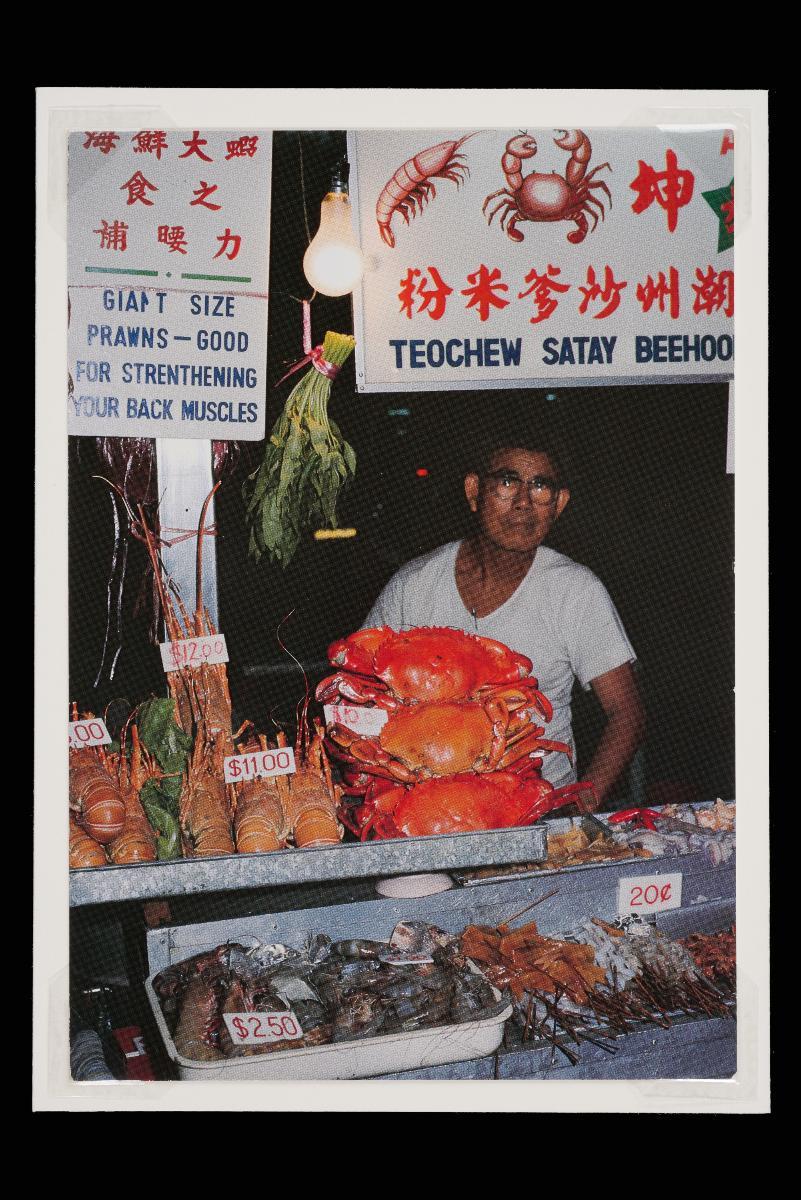

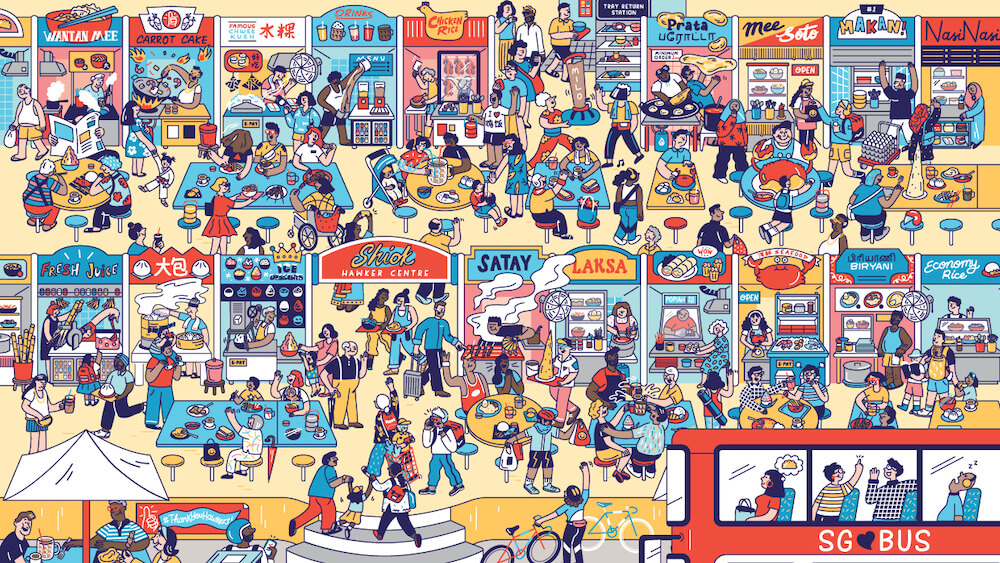

In the past, kway chap was commonly sold at roadside stalls and peddlers in Singapore. With the changing regulations in the 1960s, the roadside kwap chap stalls were relocated into hawker centres and coffee shops.

Different variations of kway chap can also be found elsewhere in the region. Compared to the dark, soya sauce-based broth familiar to Singaporeans, rice noodles are served in a white broth made from water and rice milk in the Chaoshan region in south-eastern China, where the early Teochew immigrants to Singapore hailed from. In Thailand, the rice noodles are rolled up and served in a clear broth made from a mix of Thai spices and pepper. Instead of pork, duck offal and meat accompany the rice noodles in Penang, Malaysia. In these regional variations of kway chap, the sides are served with the rice noodles in a single bowl of broth.

Associated Social and Cultural Practices

The preparation of kway chap begins with making the broth and cleaning the pork ingredients. Typically, dark soya sauce, ginger, garlic and a selection of spices, such as five-spice powder and cinnamon sticks, are added to make the broth. Pork offal is soaked in vinegar and salt and blanched in hot water. This cleans the large and small intestines thoroughly and removes their smell. Fat and hair are removed from the pork rind before blanching. Once cleaned, the pork offal is braised in a large pot of broth. Each kway chap stall has their own blend of ingredients to give their broth a unique taste.

As the broth simmers, the dry sheets of rice noodles are cut into triangular pieces and boiled or steamed. The cooked rice noodles are then drenched and served in the same broth used to braise pork offal and other ingredients, topped with shallot oil or fried shallots. Customers can choose the different ingredients they like, ranging from braised pig offal, pig’s tongue, pork rind, pork belly, as well as eggs and firm soya bean curds; these sides are served separately from the rice noodles.

Communities Involved

In Singapore, kway chap is particularly well-loved by the Teochew community. However, the dish has garnered a following from both non-Teochew Chinese and other ethnic communities over time. Most kway chap stalls are small family businesses.

Experience of a Practitioner

Mr Melvin Chew is the owner of Jin Ji Teochew Braised Duck and Kway Chap. He learnt how to make kway chap from his father, Mr Chew Suay Tee, when he was 17 years old. At the start, his parents were against him becoming a hawker because of the demanding nature of the job. However, when his father passed away in 2014, he took over the stall and now runs it with his mother.

For Mr Chew, selling kway chap and braised duck makes him feel proud to be part of the Teochew community. It gives him the opportunity to find out more about the Teochew culture and meet customers from various communities and countries. He feels that kway chap is an important part of Singapore’s food heritage, considering that the dish has been around for several generations and is a comfort food for many Singaporeans.

Present Status

Kway chap is a beloved dish of many Singaporeans. New generations of hawkers have adapted the dish to appeal to more people, such as introducing new ingredients like Japanese soft-boiled eggs and fish cake, as well as reducing the salt and sugar used for a healthier recipe.

References

Reference No.: ICH- 095

Date of Inclusion: November 2020

References

Huang, Fu Hong. ‘粿汁’ (Kway Chap). Nanyang Siang Pau. 10 August 1977. http://eresources.nlb.gov.sg/newspapers/Digitised/Articles/nysp19770810-1.2.26.5. Accessed 10 September 2020.

Jie Xi Tong Xiang. ‘揭西美食:从早晨到傍晚,一碗粿汁到底经历了什么? (Jiexi Delicacy: The Experience of the Kway Chap from Dawn to Dusk’. 25 October 2018. http://kuaibao.qq.com/s/20181102A0SYHU00?refer=spider. Accessed 11 November 2018.

Khew, Carolyn. ‘Hawker Centre 3.0: Whipping Up Tasty Ideas’. The Straits Times. 28 October 2016, 1.

Pang, Jernnine, and Orca, Jim. Not for Sale: Singapore’s Remaining Heritage Street Food Vendors. Singapore: Good Food Syndicate, 2013.

Tarulevicz, Nicole. ‘Hawkerpreneurs: hawkers, entrepreneurship and reinventing street food in Singapore’, Journal of Business Management, 58 (3) (2018): 291–302.

Tay, Leslie. The End of Char Kway Teow: and Other Hawker Mysteries. Singapore: Epigram Books, 2010.

Tay, Leslie. ‘Tong Lok Kway Chap: There’s No School like Old School!’. Ieatishootipost (blog). 5 September 2010. http://ieatishootipost.sg/tong-lok-kway-chap-theres-no-school-like-old-school/. Accessed 9 November 2018.

Zhang, Junye. ‘「泰国粿条」:别再叫它泰式米粉汤 —— 从粿条看泰国华人移民史 (‘Thai Kway Teow: Stop Calling it Thai-Style Bee Hoon Soup – Examining the Migration History of Thai Chinese’). Vision Thai. 7 November 2015. https://visionthai.net/zh-hans/article/know-more-about-kway-teow-a-local-food-in-thailand-2/. Accessed 10 November 2018.