Indian Music Traditions

There are two major traditions of Indian classical music. They are Carnatic music, a style associated with South India, and Hindustani music, a style associated with North India. It is unclear when the differentiation in the styles started, and the two traditions were considered distinct only during the 15th to 16th centuries.

Drawing from Hindu mythological and spiritual beliefs, Carnatic music is frequently played at temple festivals and as an accompaniment to bharatanatyam dance performance, while Hindustani music often accompanies the kathak dance.

Today, Indian classical music is performed at temples and festivals, and staged during productions by professional and amateur groups. There are also schools that offer classes on Indian music and dance.

Geographic location

Indian immigrants have carried Carnatic and Hindustani music to the new places they settled in.

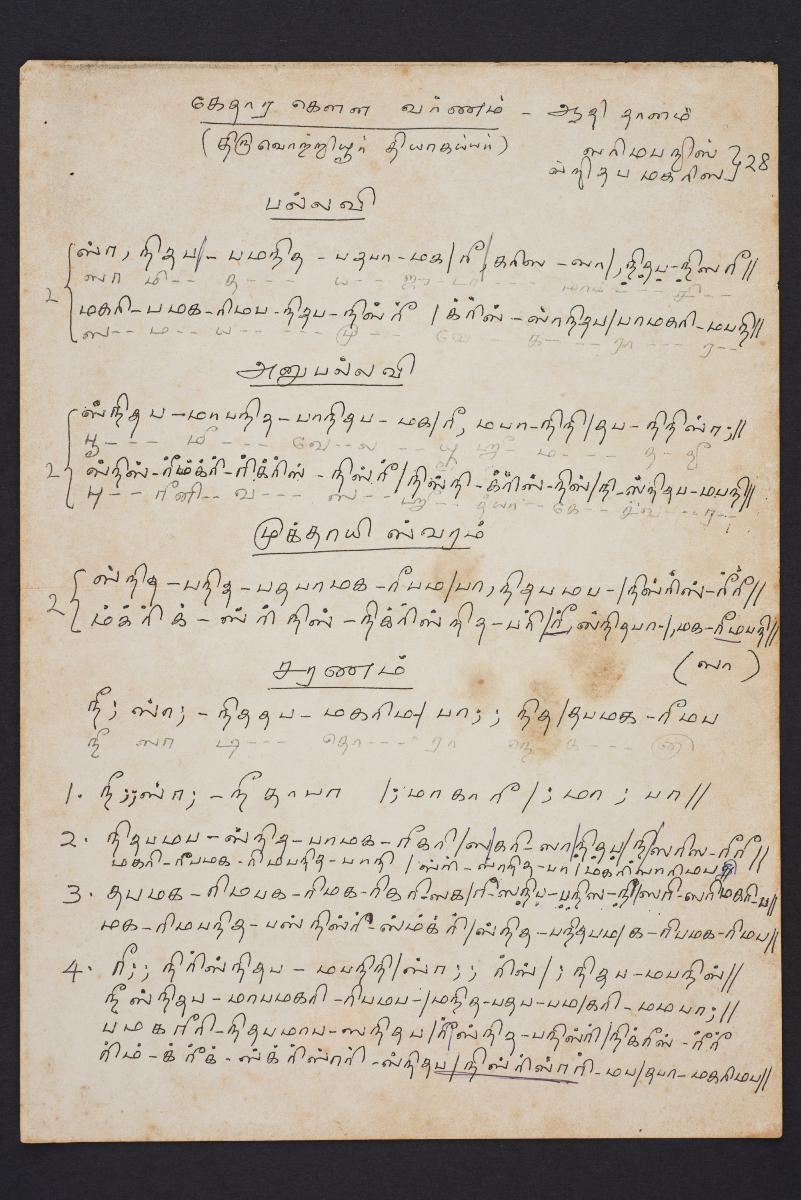

In Singapore, Carnatic and Hindustani music performances are held commonly in the schools that teach the art forms, at theatres hosting music concerts and dance programmes, as well as in Hindu temples as part of festivals.

Communities involved

In Singapore, two major institutions have been promoting Indian classical music and dance since the 1950s – the Singapore Indian Fine Arts Society (SIFAS) and Bhaskar’s Arts Academy. Besides these two institutions, there are numerous other schools and freelance teachers providing lessons. Public schools also play a role in covering aspects of these music traditions as part of the Arts Education Programme.

Associated Social and Cultural Practices

Music instruments specific to Carnatic music include the veena (a stringed instrument), the mridangam (considered the most important percussion instrument in Carnatic music), and other percussion instruments like the ghatam, ganjira, and morsing, as well as stringed instruments like the venu and violin, while Hindustani music instruments include tabla (pair of drums), sarangi (bowed, short-necked string instrument), sitar (plucked stringed instrument), santoor (stringed instrument played with wooden mallets) and clarinet.

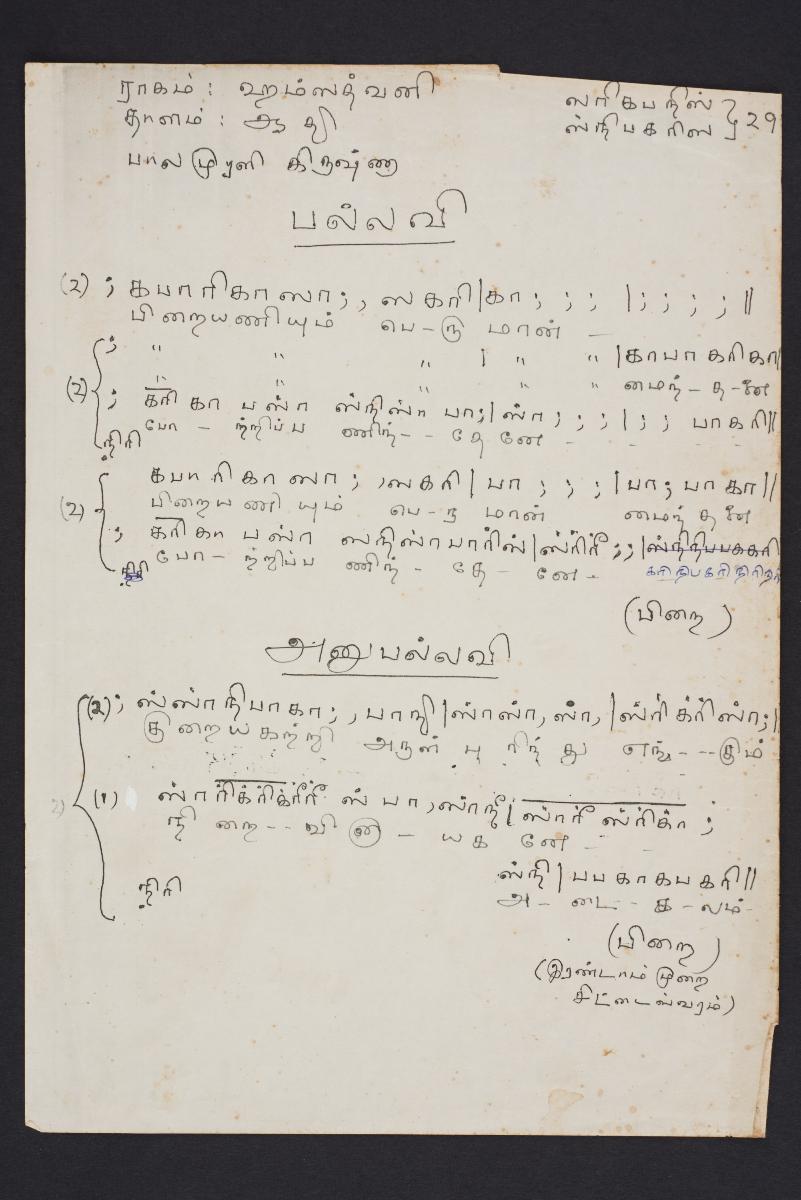

Students of Carnatic music start with geetham (simple songs) and progress to the more complicated repertoire of kriti. It takes them years to master the musical instruments. To be recognised as a vocalist or musician, students must stage a music arangetram (debut) with a full range of song repertoires to fill a concert programme. These kutcheri, or Carnatic music concerts, follow a programme of the following items: a varnam, or opening item that highlights the musical features of a raga (a melodic framework of fixed ascending and descending musical scales, characterised by musical motifs or how notes are emphasised in a melodic structure); various kriti, which typically consist of three sections in a progressive structure of variations, namely pallavi, anupallavi, and charanam; a climactic item comprising a prolonged piece with elaborate improvisations in a ragam-tanam-pallavi structure (improvisation without rhythm pattern, the addition of some rhythm, and finally the song with full rhythmic accompaniment); and conclude with a thillana, which incorporates rhythmic syllables in its melody.

Local innovations include the formation of “Indian orchestras” that incorporate both Carnatic and Hindustani musicians and instruments, and Western musical elements like choirs. For instance, the People’s Association’s Singapore Indian Orchestra and Choir has performed Carnatic music, Hindustani music, incorporated acapella music and orchestral works of fusion pieces, as well as the use of traditional Chinese and Malay instruments. The formation of such orchestras has increased the importance of a conductor’s role, which is non-existent in Carnatic music as musicians simply follow the talam or beat when performing. It has also demonstrated the multicultural aspects of Indian music traditions in Singapore.

This trend of cross-cultural performances of Carnatic music is highly sought after, with musician Mr Ghanavenothan Retnam noting a trend of “fusion music” since the 2000s. While he prefers to term them as music “collaborations” rather than “fusions”, these developments reflect the multicultural context of playing Carnatic music in Singapore.

Experience of a practitioner of Carnatic Music

Mr Ghanavenothan is a Carnatic flautist. A prolific musician, he was the first Carnatic classical musician to win Singapore’s Young Artist Award in 1995. Currently, he serves as a music director at Bhaskar’s Arts Academy and a music teacher at its teaching arm, the Nrityalaya Aesthetics Society.

Mr Ghanavenothan, whose name means “unique music”, has been acquainted with Carnatic music from a young age. His father, Mr Sri R. Retnam, was a musician, and Mr Ghanavenothan first began learning music at his father’s knee. At age seven, he came under the tutelage of Mr Pandit M. Ramalingam, his father’s friend and fellow musician. His skill grew, and he advanced further by playing in various Indian orchestras. He also played music accompaniment for bharatanatyam dances at Bhaskar’s Academy of Dance. Throughout his career, he has taken part in many shows, from television and radio, to stage shows.

Watch: Carnatic Music

Present Status

The musical scene in Singapore faces competing forms, including Western instruments. However, based on Mr Ghanavenothan’s observations at national music competitions, many students of Carnatic music are highly proficient. He also finds that there remains a sufficiently large pool of talented teachers in Singapore.

Another encouraging sign is that more non-Indian students have started learning Carnatic music – Nrityalaya Aesthetics Society has various Chinese students attending Carnatic flute courses and performing at annual concerts. With so many students learning Carnatic music, Mr Ghanavenothan believes that forms of Indian music traditions will continue to be performed and enjoyed for years to come.

References

Reference No.: ICH- 005

Date of Inclusion: April 2018; Updated March 2019

References

Rai, Rajesh. Indians in Singapore, 1819-1945: Diaspora in the Colonial Port-city. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2014.

Ramaswami, Seshan & Alurkar-Sriram, Sarita. Kala Manjari: Fifty Years of Indian Classical Music and Dance in Singapore. Singapore: Singapore Indian Fine Arts Society, 2015.

Sinha, Vineeta. Indians. Singapore: Institute of Policy Studies, 2015.

Wong, Chee Meng and Nedumaran, N. A Quest for Dance: The Life and Times of Singapore Dance Pioneer K.P. Bhaskar. Singapore: Nrityalaya Aesthetics Society, 2015.