Indian Dance Forms

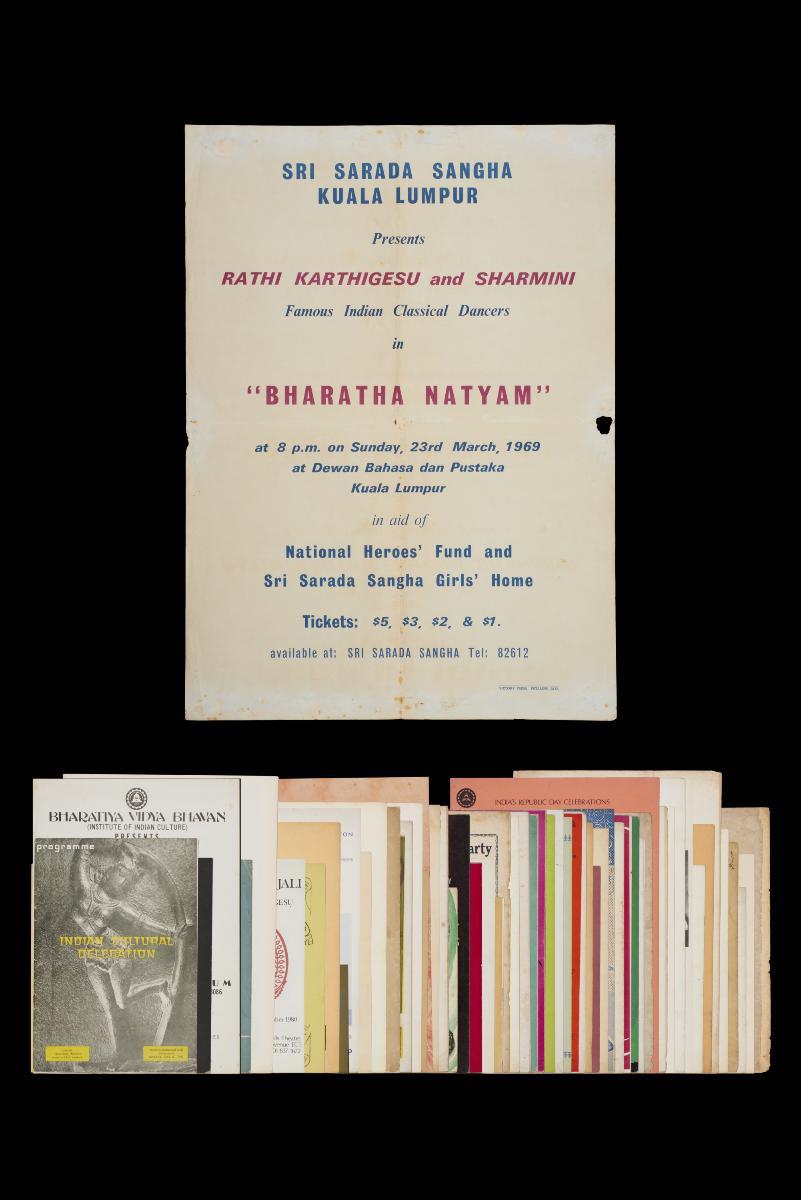

Indian dance forms in Singapore include bharatanatyam, kathakali, kathak, manipuri, kuchipudi and odissi, amongst others. The dance forms involve specific gestures, expressions, steps and postures rooted in the traditions from the various regions in India. Many of the dance forms can be traced to a sacred Hindu text known as Natya Shastra. In Singapore, there had been reports on the presence of Indian dances, theatre and other performing art forms since the early 20th century. Today, Indian dances in Singapore are performed at festivals, staged as productions, and taught through various performing arts schools and arts groups.

Bharatanatyam is a classical dance style considered to be a “living performance art”. It is a dynamic dance that incorporates elements of drama and theatre. Traditionally, the dance is performed by a solo female dance. Over time, this practice has evolved and male dancers are also present today. The stories told in the dance are usually religious and spiritual in nature, drawing on Hindu myths and legends. The dance is accompanied by live musicians who sing and play in the Carnatic tradition.

Kathakali, which literally translates to “story play”, is a complex art form in which the music, script, voice, and movements of the dancers come together to form an expressive performing art. Kathakali began to take shape from the late 17th century, born out of ideas gathered from a wide range of Kerala’s (a state in southern India) other performing art forms including, kuttiyattam (a classical dance form), kalaripayattu (a martial art of Kerala), and theyyam (ritual genres of performance). It gained prominence in Kerala due to royal patronage.

Kathak is a classical north Indian dance form involving narrative and bhakti (devotional) elements. It has evolved over the course of history, from temple-based bhakti purposes, through court entertainment during the Mughal era in India, to more modern choreography forms with emphasis on movement and rhythm. Kathak comes from the root Sanskrit word katha meaning “story narrative” and was historically performed by a class of travelling storytellers.

Geographic Location

Bharatanatyam is commonly associated with the region of Tamil Nadu in southern India. Kathakali is a theatre dance form that originates from Kerala. Kathak is associated with north India, and traditions differ with the three respective lineage-schools, Jaipur, Varanasi and Lucknow.

Though the dance forms may have originated in India, they have since spread to other regions of the world, with training centres even in Europe and United States of America.

Traditionally performed in temple grounds or religious compounds, the dance forms are increasingly performed in secular performance halls or theatres in Singapore. They are also commonly performed during annual arts events such as the Indian Arts Festival taking place at the Esplanade Theatre.

Communities Involved

Bharatanatyam is practised largely by the Tamil community in Singapore. Khathakali was made popular in Singapore due to the Malayalee diaspora from Kerala. Kathak has three schools of practice (gharanas)—Jaipur, Varanasi and Lucknow, which differ in the emphasis they place on footwork, spirituality and the style of the musical accompaniment.

Kathak practitioners usually learn kathak within the mentor-disciple (guru-shishya) model.

Organisations such as the Singapore Indian Fine Arts, the Nrityalaya Aesthetics Society, Apsaras Arts Academy and the Temple of Fine Arts teach and promote Indian dance forms in Singapore.

Associated Social and Cultural Practices

The themes for bharatanatyam are often devotional in nature, with strong connections to Hindu mythology. In Singapore, it is associated with the practices of important Hindu festivals such as Pongal and Thaipusam. Bharatanatyam dances vary according to purpose, including nritta (technical dance) where the emphasis of the dance is on speed, form and rhythm, nritya (expressional dance) which use stylised gestures to communicate story or feelings, and natya (dramatic storytelling) where the dancer or dancers adopt specific postures or body movements as they play specific characters with elements of acting.

In addition to dance movements, a critical piece of the bharatanatyam is the expression of the dancer. As the dancer does not use props to tell the story, the meaning of the dance is conveyed through abhinaya (expressions), hand gestures and the eyes. There are numerous hand gestures or hasta mudras and each has a specific purpose.

The dance is accompanied by live musicians and a vocalist, performing in a Carnatic style. This style of music is devotional in nature. The performance is a collaborative effort with musicians and percussionists playing to support the technical skills of the dancer.

The outfit for female bharatanatyam dancers is typically made of a sari material and custom-tailored for each dancer. The blouse piece or choli is covered with a piece of cloth known as dhavani. The bottom piece is either skirt or pants that includes stitched pleats which begin from the waist. Gold jewellery is also used, including a belt at the waist and ghunghru (anklets with bells). The latter is significant as it makes the rhythmic footwork of the dance audible. Vivid face make-up highlights the expressions of the eyes, while henna on the fingers highlight gestures. Male dancers have simpler costumes, using a dhoti and without vivid make-up.

For kathakali, the narrative that accompanies a performance is called attakatha. It is sung by narrators using a literary genre written in Malayalised Sanskrit known as Manipravalam. The genre comprises verses and dialogue that are usually narrative descriptions of the scene and mood of the characters. The attakatha stories depicted in kathakali are often drawn from the two Hindu epics, the Ramayana and Mahabharata, and from the devotional Bhagavata Purana.

In a kathakali performance, two vocalists take turns to sing verses in the melody and rhythm specified by the author of the attakatha without any rhythmic accompaniment. They perform using a vocal style known as sopana, derived from the Carnatic vocal tradition which often features two singers, the ponnani and the shinkiti.

The elaborate costumes and make-up of kathakali dancers are distinctive and are used to showcase different character types. Heroic male characters called paccha are identifiable by their green faces. Demons can be made out by the black colour on their faces, while abrasive and angry characters (chuvanna tadi) are identified by stylised red beards. More prominent characters representing deities such as Hanuman are identified by the blue make-up.

Kathak is often a solo that is short and vigorous, accompanied with a drumming repertoire. It has a progressive tempo, and its musical accompaniment is mostly derived from the north Indian Hindustani classical music form. Footwork is important, and solos contain sequences of swift spins, often executed on left heel. Dancers fix a set of ghunghru (anklets with bells), numbering between one and two hundred, to each ankle. This lower-body movement is contrasted with graceful movements and postures of the upper body, hands and arms.

Kathak performances include components such as the abhinaya, a set of expressive gestures or pantomime to outline the plotlines of particular narrative. The vandana is a choreographed evocation of a deity through iconic gestures and postures accompanying Sanskrit prayer, and done with reserved reverence interspersed with footwork. The end of a kathak is marked by intricate spins called cakkars, and the presentation of a kavita, a rhythmic poem. On the whole, when compared to other Indian dances, such as bharathanatyam, the tenor of kathak is more withdrawn and reserved. Costumes of kathak are not as extensive and intricate, as it reflects everyday lifestyles. Performers of both genders wear the churidar (drawstring trousers) which bunches around the ankle, accompanied by ghungroos (anklets with bells). Angharkas or coats are worn by both genders, and accompanied by skirts- producing noticeable effect during kathak spins. While costumes are not as extensive, the choice of the fabrics is often fancy and detailed with embroidery made of silk.

Experience of a Practitioner

Ms Arya Sreekumar is a student and also part of the 13-member kathakali troupe from Bhaskar’s Arts Academy in Singapore. Ms Sreekumar credits her knowledge of the art form to her mentor, Mr Kalamandalam Biju. While the troupe has been performing locally for over 20 years, Ms Sreekumar took up kathakali more recently. “Kathakali increased my awareness of the (Keralite) culture and (I) found out that kathakali is based on a lot of Hindu mythologies and stories,” she says.

Ms Sreekumar strongly feels that one should pick up kathakali by training under a mentor, in order to learn the skills of the art form. Ms Sreekumar believes that more awareness about the rich heritage and history of the art form would keep kathakali alive in Singapore. It is encouraging to see different organisations and interest groups working to promote this dance form.

Watch: Kathakali

Present Status

While anyone can learn the dance forms, dance forms such as bharatanatyam requires knowledge of the Tamil language to understand it comprehensively.

Dance forms like bharatanatyam, kathak, and kathakali are also integrated into Arts Education Programme administered by the National Arts Council in mainstream schools, while there are also organisations which conduct demonstrations and workshops. The Temple of Fine Arts in Singapore has implemented formal curriculum and examination processes, and also run workshops for women’s clubs and corporate organisations. These programmes help transmit the knowledge of dance forms such as bharatanatyam to a wide profile of people, across ages and ethnicities. Organisations and companies like Temple of Fine Arts Singapore have developed structured curricula and examination frameworks, whilst extending their reach through workshops such as those tailored for women's organisations and corporate entities. These programmes transmit knowledge of Indian dance forms to a wider public, across ages and ethnicities. Companies and artists are also imagining dance forms like bharatanatyam through film, multimedia, immersive set, sound and light design. Indian dance forms have also become a regular feature as part of Singapore's Chingay Parade, raising awareness of these dance forms among the wider public.

To become a professional in kathakali, one might require up to eight years of practice in at the Kerala Kalamandalam, a notable institution in India for the classical art forms of Kerala. Singaporean practitioners of kathakali are usually part-timers, or only practise performance arts as a hobby. However, they have helped push the envelope by producing new works, such as those that feature cross-cultural influences.

Companies are touring their major productions at international events and festivals. They have also been involved in interdisciplinary work and collaborate with diverse communities, such as the special needs community, with their social stories through performance making.

The Indian community in Singapore continues to support the various Indian dance forms and there continues to be a healthy demand for the practice in Singapore.

References

Reference No.: ICH-011

Date of Inclusion: April 2018; Updated March 2025

References

Das, Shruti. “Ancient Indian Dramaturgy: A Historical Overview of Bharata’s Natyashastra”, Research Scholar 3(3) :133-140, 2015.

Mani, A., Pravin Prakash & Santhini Selvarajan. “Chapter 6: Tamil Community and Culture in Singapore”. In Mathew Mathews (ed.), The Singapore Ethnic Mosaic: Many Cultures, One People. Singapore: World Scientific Publishing, 2018.

Meduri, Avanthi. “Bharatha Natyam-What Are You?”, Asian Theatre Journal 5(1): 1-22, 1988.

Pillai, Shanti. “Rethinking Global Indian Dance through Local Eyes: The Contemporary Bharatanatyam Scene in Chennai”, Dance Research Journal 34(2): 14-29, 2002.

Puri, Rajika. “Bharatanatyam Performed: A Typical Recital”, Visual Anthropology 17: 45-68, 2004.

Richmond, Farley. “Traditional Indian theatre”. In Siyuan Liu (ed.), Routledge Handbook of Asian Theatre. London: Routledge, 2016.

Zarrilli, Phillip B. “For whom is the king a king? Issues of intercultural production, perception, and reception in a Kathakali King Lear”. In J., Roach & J., Reineld (eds.), Critical Theory and Performance, 1992.

Zarrilli, Phillip B. Kathakali. Indian Theatre: Traditions of Performance. Mumbai: Motilal Banarsidass, 1993.

Zarrilli, Phillip B. Kathakali Dance-drama: Where Gods and Demons Come to Play. New York: Routledge, 2003.