Getai

Getai (歌台) translates literally from Chinese as “song stage” and is a form of vernacular entertainment involving live performances of music, song, and dance. These performances are staged for festive occasions or on regular weeknights. The most well-known are those held during the Zhong Yuan Jie (中元节) also known as the Hungry Ghost Festival, where the first row of seats is left empty for “spirit” visitors. A distinguishing feature of the getai performance is the predominant use of the Hokkien dialect. The interaction involves comedic banter and good humoured commentary on contemporary social issues as well as jokes and puns enabled by using multiple languages. Contemporary shows may use multi-coloured stage lights, LED props and screens, laser displays, and pyrotechnics.

The defining characteristics of Singapore getai developed during the various surges in its popularity: when the first getai troup, Da Ye Hui (大夜会) was set up at New World Amusement Park (Singapore’s first amusement park) in 1923; its heyday of the 1950s; its resurgence in the 1970s; and its new revival at the turn of the century.

Geographic Location

Getai shows are typically performed outdoors in temporary tent and stage setups. These structures would be erected in open spaces like empty fields, basketball courts or parking grounds in the public housing estates that form the residential ‘heartland’ of Singapore.

Communities Involved

Getai mainly attracts working class, middle aged to elderly Chinese Singaporeans, especially those who prefer Mandarin or a Chinese dialect as their daily communication language. However, it is not uncommon to see people from other ethnic groups and backgrounds attend getai performances as they are drawn by the entertainment. Performers comprise of those who are able to speak Chinese dialects, of diverse gender and age group. There are also getai organisers who coordinate the getai performances.

Associated Social and Cultural Practices

The association between getai and the Hungry Ghost Festival can be traced to the 1970s. Traditionally, Chinese opera and puppet shows were staged during the festival, but getai gradually supplanted them as the main attraction. Unlike the longer and more restrained narratives of Chinese opera, getai provided popular and up-tempo songs performed by a live band and singers, and eventually became a mainstay of the Hungry Ghost Festival.

The appearance of getai is characterised by loud, garish, and carnivalesque colours, outfits, and backdrops. Traditionally, the stage would feature a backdrop made of cloth or other temporary material. The contemporary setup features multi-coloured stage lights, LED props and screens, laser displays and even pyrotechnics. The outfits of performers and comperes tend to be what one may describe as “over the top”, featuring glitter, sequins, bold prints, and flamboyant accessories.

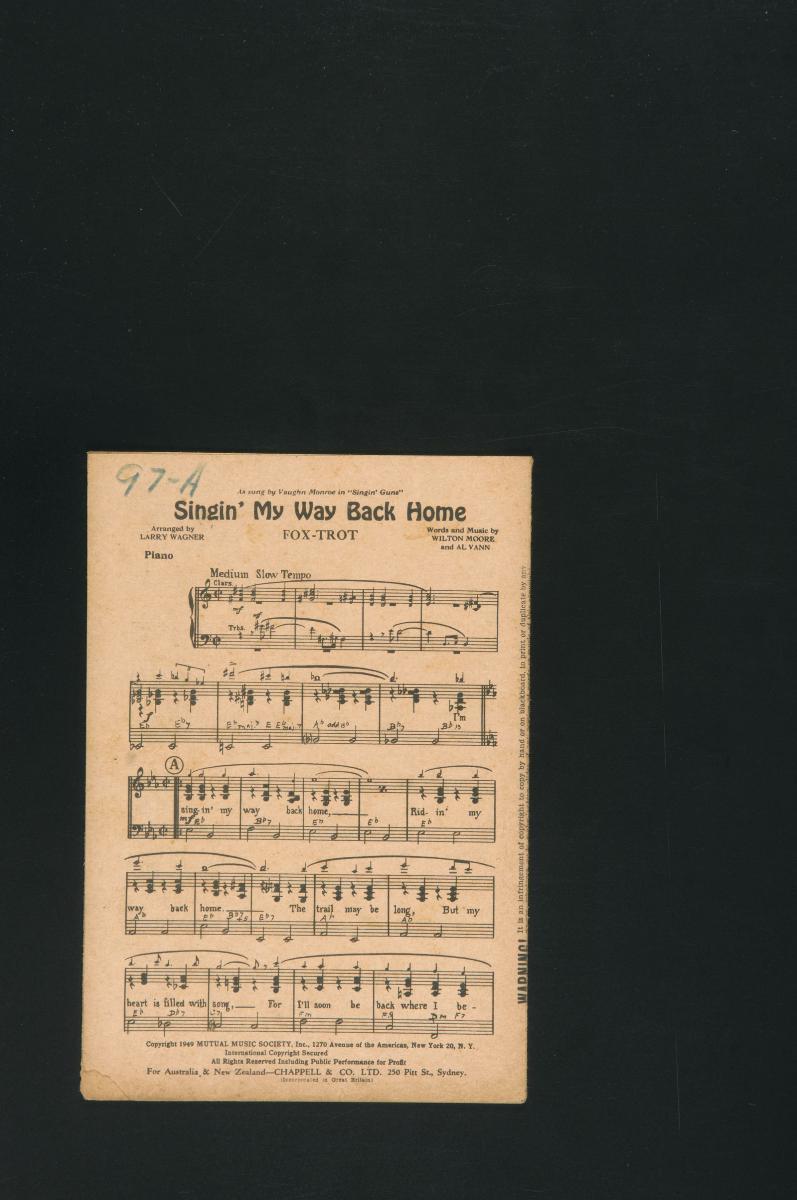

A distinguishing feature of getai performances is the use of the Hokkien dialect. In addition to Hokkien/Taiwanese songs, performers would also sing popular Mandarin and Cantonese songs from the Taiwanese and Hong Kong entertainment scenes, and sometimes Malay or Indonesian songs. In recent years, K-pop songs have also been featured.

Given the declining usage of Hokkien and other Chinese dialects in Singapore society, getai remains one of the few public platforms where the use of Chinese dialects continue to be prominently featured.

Experience of a Practitioner

For Mr Aaron Tan, getai is serious business — running his getai events company is his full-time occupation. As the owner of LEX(S) Entertainment, he has introduced a slew of changes designed to bring getai back into the mainstream. His shows are conducted on more professional staging, compared to the plywood backdrops of old, and use LED lighting and digital sound systems. He provides HD live-streaming of his shows through the Rings TV app, a move that has proven hugely successful — their channel has approximately 40,000 subscribers and is streamed to Singaporean and overseas audiences.

Another big change Mr Tan made was to introduce timetabling for his shows. While it appears to be a minor detail, the past practice of not announcing a show’s line-up had often led to squabbles between performers. Hence, timetabling is now common practice in the local getai scene.

Present Status

The format of getai was modernised in the 2000s. Stage structures became more elaborate with complex lighting systems, laser effects, pyrotechnics, digital sound systems, and screen displays. There has also been increased attention to getai in mass media. Getai may also attract a younger audience especially when it is staged for special events. For instance, the first getai talent-reality show, “Getai Challenge: The Ultimate Battle”, received a large youth viewership when it was screened on Channel 8 in 2015. Local filmmaker Royston Tan wrote and directed the 2007 movie 881, a musical-comedy-drama about the getai scene in Singapore. The film was widely publicised in the English-language and appealed to audiences beyond the usual Mandarin-speaking support-base of the getai scene. The soundtrack for 881 put a new spin on traditional Hokkien getai songs, appealing to a wider audience and generated more awareness and appreciation for these songs.

Following the success of 881, more young people were reportedly seen attending getai performances. The popularity of getai has also reached new heights in recent years. In 2011, a getai extravanganza was staged for the first time on Orchard Road at the Ngee Ann City public square on the first day of the Hungry Ghost Festival. The three-and-a-half-hour event drew a crowd of more than 10,000.

The popularity of getai appears to be relatively stable at present. Media commentaries in 2017 indicate that a younger generation of performers are being drawn to the getai circuit. Getai in the second decade of the 21st century is adapting to the times by harnessing the participatory, shared nature of social media to appeal to a wider mainstream audience. Given these developments, getai’s existence seems assured for the future.

References

Reference No.: ICH- 057

Date of Inclusion: March 2019

References

Chan, Brenda. “Gender and Class in the Singaporean Film 881.” Jump Cut: A Review of Contemporary Media 51, Spring 2009, https://www.ejumpcut.org/archive/jc51.2009/881/text.html. Accessed 4 April 2018.

Chan, Rachel. “The Ah Beng Subculture: The Influence of Consumption on Identity Formation among the Malaysian Chinese.” Social Science Review Network, 2011.

Chong, Terence. “Ethnic identities and Cultural Capital: An Ethnography of Chinese Opera in Singapore.” Identities, 13 (2): 283-307, 2006.

Liew, Kai Khiun and Brenda Chan. “Vestigial Pop: Hokkien Popular Music and the Cultural Fossilization of Sub-alternity in Singapore.” Journal of Social Issues in Southeast Asia, 28 (2): 272-298, 2013.

Lim, Kevin. “Getai: Not a lost act.” The Straits Times, 11 September 2017.