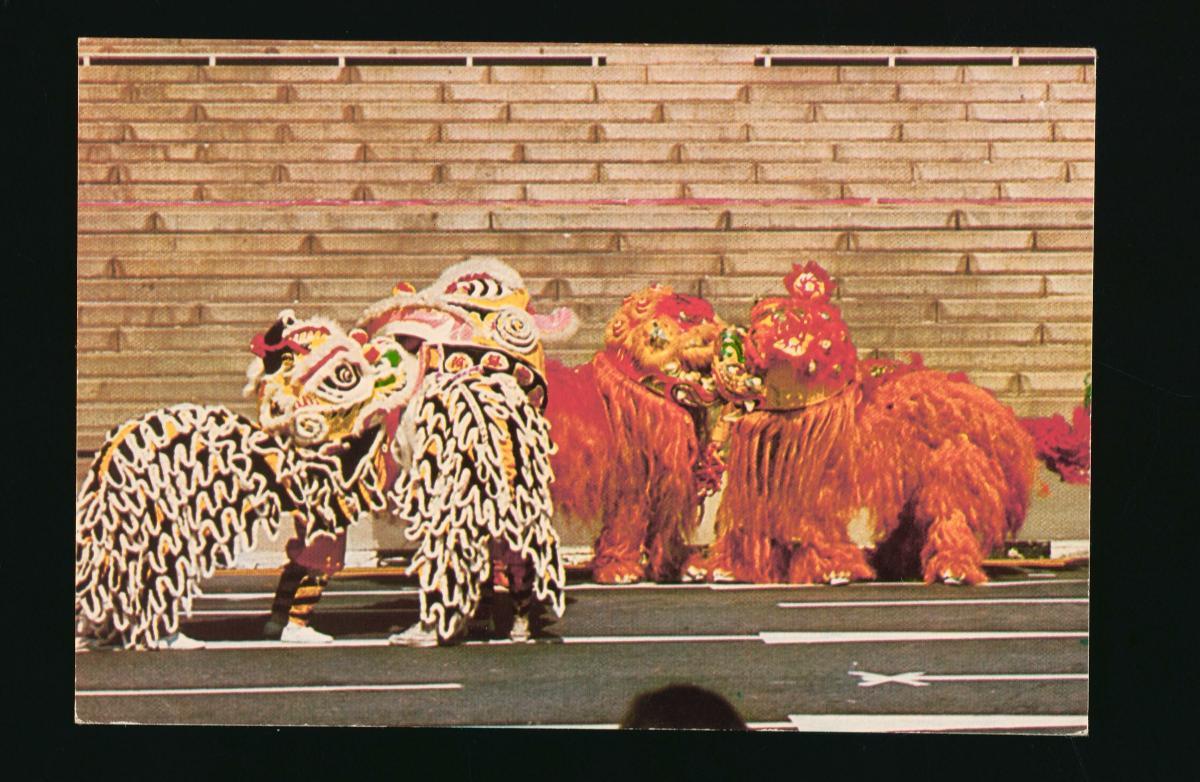

Dragon Dance

The dragon dance consists of a group of performers wielding a dragon prop mounted on poles to the rhythm of resounding drum beats. A typical dragon dance lasts 30 minutes with the performance comprising about 12 formations. Historically linked to Chinese rain rituals, the dragon dance is usually performed today during festive events such as Chinese New Year and religious events at Chinese temples.

A typical dragon dance comprises two key props mounted on poles and held up by a group of performers: a long structure of a dragon, and a separate pearl held up by just one performer. Before each performance, the dragon and pearl are prepared according to a ritual in which the guest-of-honour is invited to brush on parts of the props to imbue them with “life”. Then, following the lead of the pearl, performers move the dragon according to the rhythm of the music, mimicking an attempt to “capture” the pearl.

Dragon dance arrived on Singapore’s shores with Chinese immigrants in the 19th century. According to the Singapore Dragon and Lion Athletic Association, the first troupe here was established by the Fuzhou Carpenter’s Association in 1927. Since then, the popularity of dragon dance has grown.

Geographic Location

Dragon dance is practised in various countries including Malaysia, Philippines and Hong Kong. In Singapore, dragon dance is performed in public venues during festivities, as well as in Chinese temples.

Communities Involved

Dragon dance is popular among the Chinese community in Singapore, although there have also been performers of other ethnicities. Audiences of dragon dance performances are diverse and often multi-ethnic.

Associated Social and Cultural Practices

The strong interest in dragon dance has led to the birth of several innovations and adaptations. A Singaporean innovation is the luminous dragon. First used in 1967, the dragon prop was painted with luminous paint and illuminated with UV light during the performance. It was a huge hit, and luminous dragon dance competitions were subsequently held in Singapore and other neighbouring. Singapore is also the birthplace of the lotus dragon, which debuted in the 1995 Chingay Parade. Designed with lotus flowers, this version of the dragon dance can be performed in the rain.

Another more general adaptation is the music and instruments used. In the past, accompanying music was played with instruments similar to those used for Chinese opera, which were smaller in size and more suited for stage performances. As dragon dance performances in Singapore are usually held at large open-air venues, big drums and gongs are used instead.

In recent years, the Singapore Wushu Dragon and Lion Dance Federation has held non-conventional competitions such as the Speed Dragon Challenge. Troupes are required to finish a fixed set of formations as quickly as possible using a seven-section dragon, rather than the standard nine-section dragon. They are also allowed to use non-traditional music, or no music at all.

Another variation is the fire dragon, traditionally performed in China in autumn to celebrate a good harvest. In China, the body of the dragon is typically made of paper and each section of the dragon is lit by candles or filled with firecrackers. The performance ends when the dragon is completely burnt.

In Singapore, the Mun San Fook Tuck Chee temple, located at Sims Drive, performs the fire dragon as part of the rituals conducted during the birthday of the Earth Deity (大伯公 Da Bo Gong). The practice here follows the Guangdong variation where the dragon prop is made from hay instead of paper. For this variation, the body of the dragon is filled with incense sticks, instead of firecrackers or candles.

When performed in Hong Kong, the dragon is tossed into the sea at the end, signifying its return to sea. In Singapore, the dragon is laid in a corner to burn up, signifying its ascent to heaven.

Experience of a Practitioner

For Mr Ting Wan Kee, dragon dance is a family affair, and three generations of his family has been involved in some way or another. His father, Mr Chen Shao Kun, founded the Singapore Dragon & Lion Athletic Association in 1959. As Mr Chen was also the Association’s Head Coach, Mr Ting was exposed to dragon dance from a young age. When he was nine, he started foundational training in wushu, and moved on to dragon dance training two years later. After completing his National Service, he took up a coaching position and eventually took over his father’s position as Head Coach. Mr Ting is also the Association’s Secretary-General and his children are involved in the association.

Present Status

In Singapore, the number of dragon dance performers are slowly dwindling. In 1999, Mr Chen wrote that professional troupes require up to 70 performers. Although present-day troupes have trimmed their crews to a lean 20 performers, it is difficult to sustain even this number. Despite drawing some younger and non-Chinese performers in recent years, fewer people are entering the trade in general.

Funding is another concern raised by some troupes. Mr Ting said that dragon dance requires huge financial expenses and is not very profitable. Customers often request for new props, and the raw materials have to be imported from abroad at a significant cost. Nonetheless, Mr Ting considers it encouraging that private companies sponsored the annual dragon dance competitions in 2017 and 2018. Troupes also help each other by sharing practice spaces or splitting the rental costs of such venues.

There are efforts by practitioners to keep the art alive. For instance, Mr Ting is also the chief superintendent of the international Foochow Dragon Federation, which aims to promote the Foochow-style dragon dance. In addition, he has put his skills at prop-repairing into running a company that produces dragon props for other troupes. Mr Ting actively promotes dragon dance, and even teaches it overseas.

References

Reference No.: ICH-054

Date of Inclusion: March 2019

References

Ang, Yik Han. 乡情祠韵: 沙冈村和万山福德祠的流变与传承 (A Kampong and its Temple: Change and Tradition in Kampong Sar Kong and the Mun San Fook Tuck Chee). Singapore: Mun San Fook Tuck Chee, 2016.

Chong, Wing Hong. “From masquerade to show of skills.” The Straits Times, 16 November 1988.

Singapore Dragon and Lion Athletic Association,星洲龙狮迎千禧(Singapore Dragon and Lion Dance Welcoming the Millenium). Singapore: Singapore Dragon & Lion Athletic Association, 1999.

Singapore Wushu Dragon and Lion Dance Federation. "Singapore Wushu Dragon and Lion Dance Federation". http://www.wuzong.com/en/index.php. Accessed 4 January 2018.

Tan, Dawn Wei. “Burning desire to keep ‘fire dragon’ rite.” The Sunday Times, 9 March 2008.

Xie, Xiaolong, Xiao Mouwen & Liu Feizhou. 舞龙舞狮教与练 (The theory and practice of dragon dance and lion dance). Changsha: Hunan University Press, 2012.