Dondang Sayang

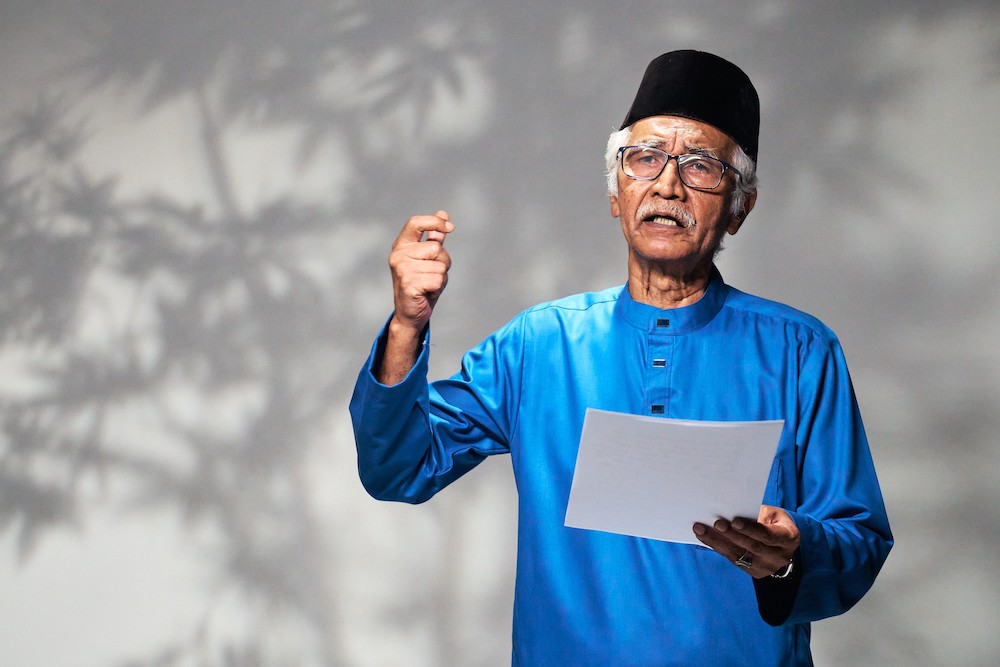

Dondang sayang is a musical and poetic art form, involving the singing of pantun, or four-line verses. In a performance, two singers would typically try to outwit each other in an amicable and teasing manner on topics such as love or good deeds. The singers are accompanied by a small band of musicians playing the violin, two Malay rebana drums, and a gong. Other instruments may include guitars, tambourines, and flutes.

The history of dondang sayang traces back to Malacca in the 14th and 15th centuries. It was a popular form of entertainment among the Malay royal families and nobles, before eventually spreading to the public and being performed at festivals and celebrations. The art form found its way to Singapore in the 19th century when Malacca came under British rule as part of the Straits Settlements.

Geographical Location

Dondang sayang is practised mainly by the Malay and Peranakan communities in Singapore and Malaysia. It is performed in homes, as well as at public venues and theatres.

Communities Involved

In Singapore, the practice initially started out among the Malays. It was later adopted by the Chinese Peranakans. Other than the Chinese Peranakans, the Portuguese Eurasian and Chitty Peranakan communities also used to take part in dondang sayang performances.

As a tradition in the respective communities’ cultures, dondang sayang helps to build their collective identity in Singapore. For example, in 1910, the Gunong Sayang Association was set up by the Chinese Peranakan community to do just that and the association continues to put on dondang sayang performances.

Various performing arts groups had also adapted dondang sayang music into their performances, making the art form integral to the wider culture and heritage of Singapore.

Associated Social and Cultural Practices

The Peranakan dondang sayang and the Malay counterpart share similarities, with the former being performed in Baba Malay language.

The pantun is often improvised on the spot, hence requiring the singer to be highly proficient in the language. The art also calls for a sound knowledge of customs and references in order to compose a pantun that is relevant to their lifestyle and culture.

As a tradition in Peranakan and Malay culture, dondang sayang helps the respective communities to build their collective identity in Singapore.

Experience of a Practitioner

Mr Gwee Thian Lye is in his 70s and is possibly one of the last notable Peranakan dondang sayang practitioners in Singapore. Mr Gwee learnt the art from his father, Mr Gwee Peng Kee, who was also a prominent Peranakan dondang sayang singer. Although he has retired from performing, Mr Gwee is immensely proud to have inherited his father’s legacy as a dondang sayang expert. It is a strong part of his identity because of his deep love for it and it allows him to connect with his heritage. Mr Gwee believes anyone with a passion for dondang sayang is able to learn and perform it. Mr Gwee is heartened to have been approached to contribute his story, and is happy to be involved in research on dondang sayang and its associated culture.

Watch: Peranakan Dondang Sayang

Present Status

The Gunong Sayang Association continues to safeguard and put up dondang sayang performances.

In recent years, a lack of exposure to the art form has made it hard for the younger generation of the Peranakan community to develop and maintain interest in it. They are also no longer fluent in Baba Malay or as knowledgeable about the respective communities’ culture. More modern forms of music and entertainment have also helped to push this practice to the backseat. Adding to the challenge is the art form itself, which is inherently difficult to master.

Nonetheless, encouraging student research on dondang sayang and Peranakan culture, as well as documentation are ways in which the living culture surrounding the dondang sayang can be kept alive.

References

Reference No.: ICH-003

Date of Inclusion: April 2018; Updated March 2019

References

Amend, James M. Negotiation of identity as theme and variation: the musical art of dondang sayang in Melaka, Malaysia. Florida: Florida State University PhD thesis, 1998.

Dhoraisingam, Samuel S. Peranakan Indians of Singapore and Melaka: Indian Babas and Nonyas—Chitty Melaka. Singapore: Institute of Southeast Asian Studies, 2006.

Juita, Ning. “Back to the days of tender tussle of the pantun.” The Straits Times, 25 May 1988.

Rudolph, Jeurgen. Reconstructing identities: a social history of the Babas in Singapore. Aldershot: Ashgate, 1998.

Tan Chee Beng. Chinese Peranakan heritage in Malaysia and Singapore. Kuala Lumpur: Fajar Bakti, 1993.

Tan Sooi Beng. “Peranakan street culture in Penang: towards revitalization.” Journal of the Malaysian Branch of the Royal Asiatic Society, 82 (2): 157-166, 2009.

Thomas, Phillip L. Like tigers around a piece of meat: the Baba style of dondang sayang. Singapore: Institute of Southeast Asian Studies, 1986.