Chingay

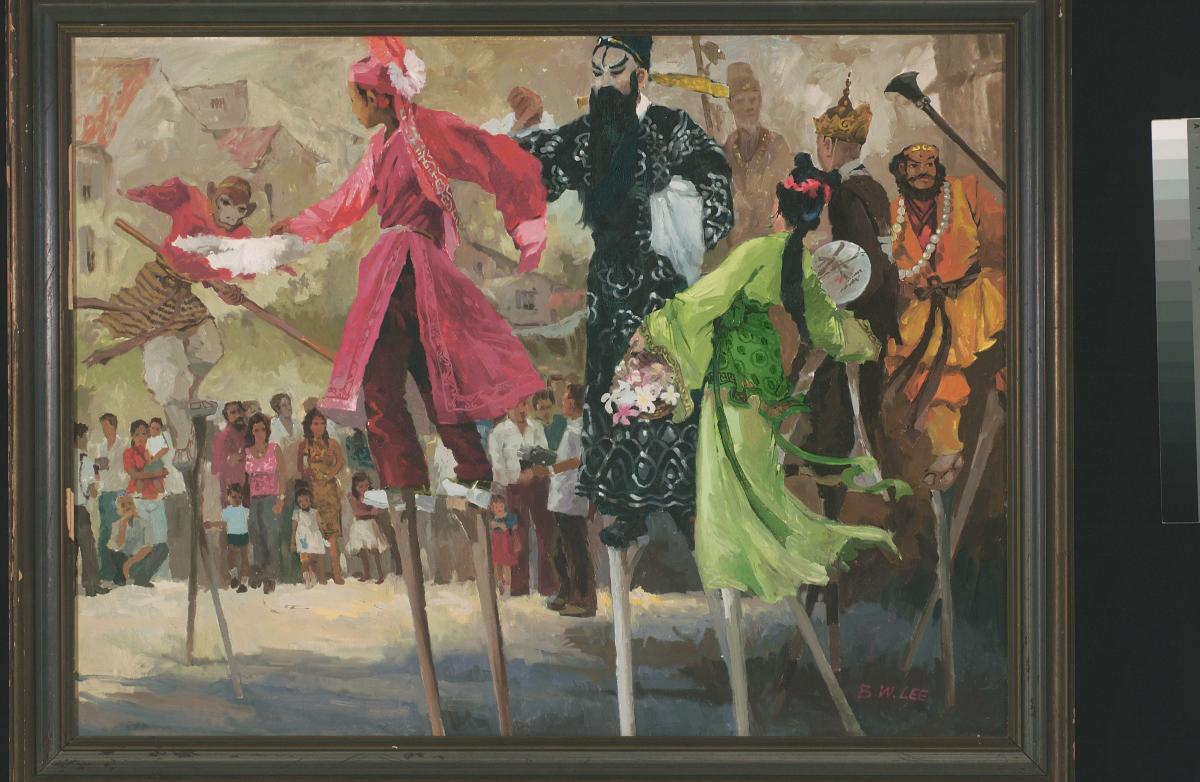

The word Chingay is derived from the Mandarin word 妆艺 (zhuangyi) which means the art of costume and masquerade in Hokkien dialect. Chingay – a festival which has long roots in Singapore’s cultural history has grown to become one of the most significant events in the country’s socio-cultural calendar. Today, Chingay is commemorated through an elaborate parade cherished by Singaporeans across ethnic communities. The parade is renowned for its dazzling display of floats, intricate props and structures, and cultural performances from Singapore and the world over. Usually held during the second week of the Chinese New Year, Chingay is celebrated by Singaporeans, residents, and international participants alike. The commemoration of Chingay in Singapore offers a glimpse into the dynamism of Singapore's multi-culturalism and a unique blend of tradition, innovation, arts, and culture.

Geographic Location

Chingay is believed to have originated in Southern China, where various records from the early 19th century mentioned children being dressed up and carried on platforms in processions. These platforms were said to have been adorned with flags, lanterns, and intricately decorated to depict folk tales, religious deities, and historical scenes, while accompanied by an ensemble of cymbals, drums, and gongs. While it is difficult to ascertain exactly when or how Chingay arrived in Southeast Asia, it is believed that migrants from Southern China brought the practice to the British settlement of Penang, and thereafter, Singapore during the early 19th century, where it has evolved and continues to be celebrated annually as part of Chinese New Year festivities. Chingay also continues to be celebrated in the cities of Penang and Johor Bahru in Malaysia.

In Singapore, Chingay processions were initially organised for religious festivals devoted to Taoist deities such as Tua Pek Kong and Mazu, in lavish processions that stretched through the streets of Telok Ayer and involved vast numbers of the Cantonese, Hokkien, and Teochew communities, as well as spectators alike. These processions carried on up till the late 1920s when communities and clans abolished the practice of organising grand processions in favour of community-specific and prudent processions. Today, while processions in honour of Taoist deities continue to be observed in temples around Singapore such as Thian Hock Keng Temple, the Chingay procession has since evolved into a resplendent parade and cultural phenomenon involving a myriad of communities and performances.

Communities Involved

The annual parade in Singapore involves multiple different communities, contributing to various roles ranging from choreographers, performers, and volunteers of varying age, gender, and ethnicity – many of whom are intergenerational participants who have participated in the Chingay Parade over the years. They are usually part of over 100 groups including grassroots organisations, community and youth groups, performing arts groups, corporate groups, schools, cultural associations, and individual contributors – recruited from an open call for participation each year.

Since the inception of the parade in 1973, dance practitioners have been involved in choreographing different performance items to showcase a range of arts and cultural elements in their dance routines. The Parade has evolved to include practitioners from a wide range of performing art forms and community groups such as artists, singers, poets, musicians, magicians, as well as interest groups, and hobbyists – serving as a unified platform for a myriad of arts and cultural forms coming together.

During larger-scale Chingay Parades prior to the COVID-19 pandemic, some 2,000 community volunteers are involved annually in different roles ranging from performers management, to crowd management, to logistics management throughout the parade. While numbers have been reduced owing to restrictions brought about by the pandemic, the community continues to play an integral part in the successful execution of the annual Chingay Parade – many of whom return to contribute in some way year after year.

The Chingay Parade also receives and welcomes participants from all around the world, having had thousands of international performers over the years; from ASEAN neighbours such as Indonesia and Thailand, distant neighbours such as Japan and Korea, to as far-off as Brazil. The communities involved - both local and international - are at the heart of the annual parade.

To further encourage participants and residents to co-create different elements to be presented at the Chingay Parade, the People’s Association (PA) introduced the Community Engagement Programme (CEP) in 2012 – where grassroots organisations play a central role in facilitating community involvement by engaging their residents to contribute through a range of initiatives. For example, the ‘We’ve Got Talent (WGT)’ initiative was launched in 2020 to encourage members of the community to submit videos of their artistic talents to be featured at the Chingay Parade. Additionally, the ‘D:2 Dance Competition’ was also launched in 2020; to engage youths passionate in dance to choreograph routines which infused cultural elements with contemporary dance forms, and showcase them at the Chingay Parade. Another example of co-creation with the community is the introduction of ‘Chingay Mini Floats’ in 2021 as an opportunity for community artists and residents to come together to design and build floats for the Chingay Parade.

Associated Social and Cultural Practices

Following the ban on fire-crackers in June 1972, which was a popular feature of Chinese New Year celebrations in those days, then-Prime Minister Lee Kuan Yew suggested the staging of a Chingay Parade to reinvigorate community involvement in ushering in the Chinese New Year. The parade we know of today was conceptualised from the idea that the lights and sounds of a parade would spark the festive mood as firecrackers did in the past, which was a custom believed to drive away evil spirits.

Thus, the first modern instalment of the Chingay Parade in Singapore was held on 4 February 1973, with the participation of some 2,000 performers. From its modern inception in 1973, the Chingay Parade has evolved over the years into a multi-cultural event that includes participants from across Singapore, the region, and the world. In the earlier years, the parade was themed around the Chinese zodiac animal for the new lunar year. In more recent years, the theme of the parade is uniquely curated each year. For example, in 2021, the parade was themed “Light of Hope,” in relation to overcoming challenges brought about by COVID-19 together. While the theme of the parade changes each year, what remains consistent are the multifarious performers and floats coming together in a unified showcase of culture and heritage. Performers range from seasoned practitioners who participate annually, to grassroots members, corporate groups, community groups, youth groups, interest groups, and volunteers across the community.

The floats are one of the key characteristics of the parade ever since its first modern instalment; serving as awe-inspiring and tangible representations of art, culture, design, and technology that continue to evolve with each year. The preparation of floats used in the parade also present the opportunity for the community to come together. For example, in 2022, over a thousand community artists and residents from various groups across Singapore were involved in the creation of 17 floats that were showcased in the parade, and presented at a travelling exhibition to be enjoyed and appreciated after the parade.

Experience of a Practitioner

Mr Fan Dong Kai has been the artistic director of the Chingay Parade since 2003. A renowned dancer and choreographer by training, his artistic vision and wealth of experience, together with his team and community of performers and volunteers, work tirelessly to stage the annual parade. Preparation for each parade takes up to 12 months, and according to Mr Fan, the parade is the culmination of the preparatory journey, of which the community of performers and volunteers are at the heart of it all. He cites that each year presents unique challenges, which require persistence, willingness, and coordinated effort across multiple communities to pull off. For example, over the past 2 years, digital presentation took centre-stage, and Mr Fan used the opportunity to present the Chingay Parade in a unique format that included choreographed computer-generated imagery (CGI) effects for dragon dance and pole act performances, special effects, and various interactive floor projections, for example. These use of technology to showcase traditional art forms allow them to appeal to new audiences. Thus, the focus on a digital experience seeks to appeal to younger audiences, but at the same time, find a delicate balance which continues to captivate other audience segments. Mr Fan takes immense pride in the Chingay Parade becoming a cultural phenomenon with a lasting legacy, and relishes in the opportunity to unite diverse individuals, groups, communities, and their respective cultural art forms into what he regards as a “multicultural symphony.”

Present Status

The Chingay Parade has continually evolved and grown from a street procession held on Jalan Besar in 1973, to Orchard Road in 1985, to City Hall in 2000, to the F1 Pit-Building in 2010, and as a first -owing to the COVID-19 pandemic – a fully-digital parade in 2021, and a hybrid format in 2022. It has also grown from a 14-item show in 1973 to an endearing street parade boasting a stunning array of performers, community floats, jugglers, percussionists, lion dancers, dikir barat groups, kathakali dancers, acrobats, and fireworks, amongst many others. In addition, ‘Chingay@Heartlands’ has been organised since 1997 to bring snippets of the main Parade - from selected floats to featured performances - to different residential districts, thus, enabling more residents to experience the Chingay Parade. To keep up with times, digital initiatives such as live-streaming the parade online and on Facebook have also allowed the festivities to remain accessible to Singaporeans and international audiences both here and abroad.

Since 1987, the parade has evolved with both local and global influences, involving performers not just from Singapore, but countries as far as Japan, Brazil, and Slovenia - all of whom add a distinctive touch of their art and culture - from J-pop to Samba - to the Chingay Parade. The Chingay Parade has evolved from a procession that celebrated Chinese culture during the Chinese New Year, into a dazzling display of Singapore’s multi-ethnic diversity – with practitioners, performers, and spectators coming together in unified spirt in what has come to be known as the ‘People’s Parade.’

References

Reference No.: ICH-098

Date of Inclusion: March 2022

References

Attractions@SG. “Chingay.” Accessed 7 January 2022. https://sites.google.com/site/attractionsg50/events-calendar/feburary/chingay

Chingay Parade Singapore. “Light of Hope.” Accessed 21 January 2022. https://www.chingay.gov.sg/about-us/chingay-2021/light-of-hope

Chingay Parade Singapore. “The Chingay Story.” Accessed 10 January 2022. https://www.chingay.gov.sg/about-us/the-chingay-story

Chingay Parade Singapore. “The Chingay Timeline.” Accessed 12 January 2022. https://www.chingay.gov.sg/about-us/the-chingay-timeline

Ng, Keng Gene. “Chingay to go digital next year, and feature song and dance videos submitted by public.” The Straits Times. Published 26 November 2020. https://www.straitstimes.com/singapore/chingay-to-go-digital-next-year-and-feature-song-and-dance-videos-submitted-by-public

People’s Association and The Photographic Society of Singapore. Chingay, 妆艺: Singapore on Parade. Singapore: People’s Association (2007).

People’s Association. Tales of Chingay – Celebrating 40 Years of Chingay. Singapore: People’s Association (2012).

People’s Association. The People’s Parade – 45 Years of Chingay. Singapore: People’s Association (2017).

Singapore Hokkien Huay Kuan. Transcending Centuries: A Chronicle of SHHK, 180 Years of Historical Articles (Volume 1). Singapore: Singapore Hokkien Huay Kuan (2020).

Tan, K. H. The Chinese in Penang: A Pictorial History. Penang: Areca Books (2007).

Tay, Matthias. “Performers from record 15 countries to take part in Chingay 2015.” Today. Published 14 January 2015. https://www.todayonline.com/singapore/performers-record-15-countries-take-part-chingay-2015

The Straits Times. “Chingay Procession.” Published 31 October 1928.

The Straits Times. “In Pictures: Chingay parade through the years.” Published 27 January 2017. https://www.straitstimes.com/multimedia/photos/in-pictures-chingay-parade-through-the-years

Yee, Xiang Yun. “Johor Chingay fest.” The Star. Published 16 February 2022. https://www.thestar.com.my/news/nation/2022/02/16/johor-chingay-fest-to-proceed-from-feb-19-to-22-on-a-smaller-scale-with-strict-sop-say-police