Chinese Puppetry

Chinese puppetry (also known as puppet theatre) is performed in various Chinese dialects, depending on the region it originated from, with sponsors, puppeteers, and audiences congregating based on their native dialect and hometown. The art form came to Singapore with the influx of Chinese immigrants, and different waves of migrants helped shape the development of puppet theatre in Singapore.

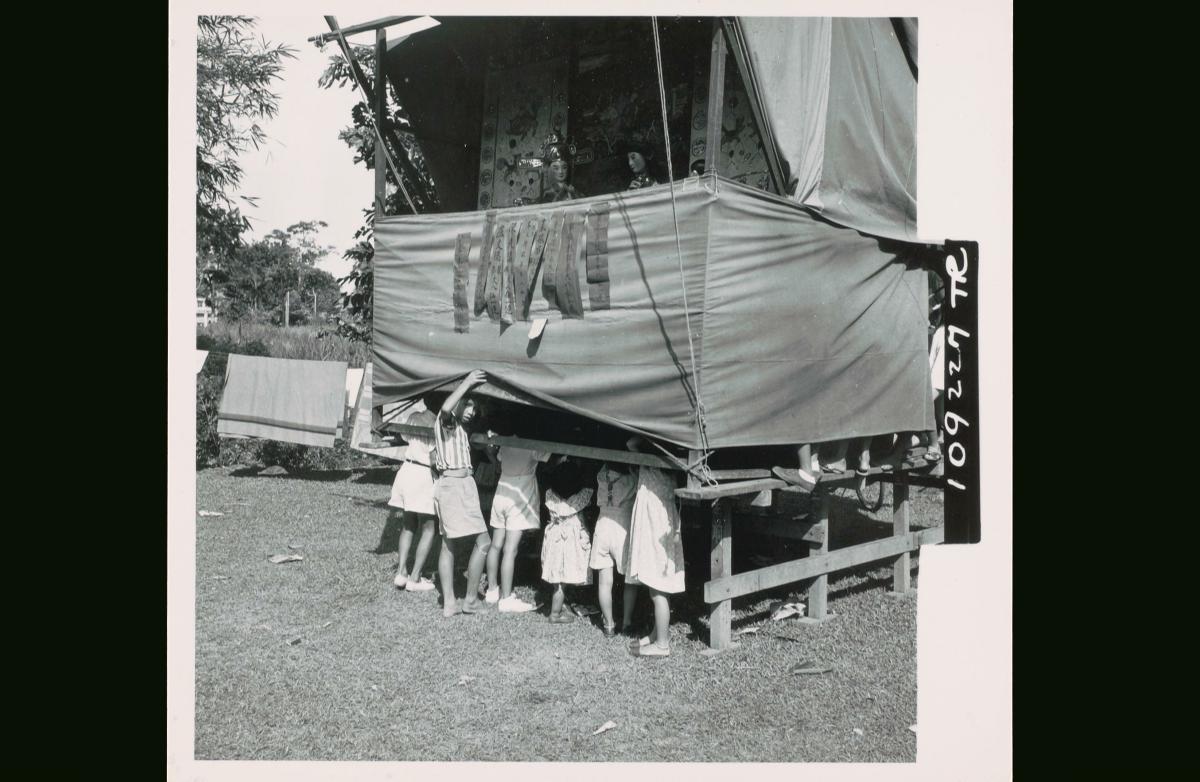

Traditionally, puppet performances are staged mainly for deities. This religious context stemmed from the puppets’ origins as objects used in funeral rites as early as the Zhou dynasty. Today, puppet troupes continue to perform in religious institutions such as temples. Devotees may invite troupes to provide entertainment for deities in return for their blessing and protection, particularly during the deities’ feast days. In recent years, secular puppet performances have been staged in a bid to keep the art form relevant to a wider audience.

Geographic Location

Chinese puppet theatre is found in various parts of the world with Chinese communities.

In Singapore, though the puppet performances are associated with religious institutions, performances are also common outside of the temple setting. Secular puppet performances are staged for general public in performing art venues and theatres.

Communities Involved

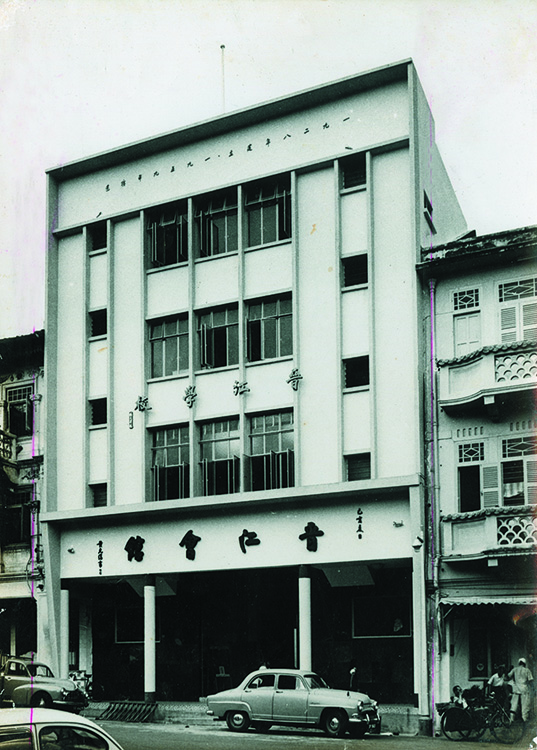

The communities involved in Chinese puppetry mirror closely with the five main types of Chinese puppets found in Singapore: Hainanese rod puppets, Teochew iron-stick puppets, Hokkien string puppets, Hokkien glove puppets, and Henghua string puppets. Due to the differing waves of Chinese immigrants, the Hokkien and Teochew communities have had longer legacies pertaining to the respective puppet forms in Singapore. The large size of the Hokkien community and the penetration of the Hokkien language across different dialect groups and ethnic communities in Singapore has also resulted in the popularity of the art form beyond the Hokkien community.

Puppet troupes include established Hokkien puppetry troupes-- Jit Guat Sin (日月星), which continue to practice their craft although their golden era may have passed. For Hainanese rod puppetry, there are two remaining troupes — San Chun Long (三春隆) and Tien Heng Kang (新兴港琼南剧社). Of the two, San Chun Long is the oldest known Hainanese rod puppet troupe in Singapore. As for Teochew iron-stick puppetry, Sin Ee Lye Heng (新怡梨兴) is the only troupe active today. For Henghua string puppetry, many troupes flourished and perished and the one active troupe is Sin Hoe Ping (新和平). Sin Hoe Ping has also established a Hokkien troupe under the same name that performs both string puppetry and glove puppetry.

Associated Social and Cultural Practices

A typical traditional Chinese puppet performance comprises puppeteers who manoeuvre the puppets behind the stage, and musicians who accompany the performance with instruments such as clappers, cymbals, flute, erhu (two-stringed bowed instrument) and suona (double-reeded horn). These puppet performances usually depict classic tales and stories that are passed down through generations.

In the past, Chinese puppet performances were popular as forms of entertainment for overseas Chinese who missed their hometowns. Chinese puppet troupes would also be invited to perform at special occasions such as birthday celebrations and weddings. In recent years, there have been a number of theatre practitioners in Singapore who have weaved elements from traditional Chinese puppetry with contemporary forms to reach out to newer audiences, and are promoting the art form through stage productions and outreach programmes to schools and the general public.

Experience of A Practitioner

Mr Chew Keng Boon is the current troupe leader of the Hainanese rod puppet troupe, San Chun Long (三春隆). The puppeteers and musicians in the troupe have an average age of 70 years, while Mr Chew, a musician, is relatively young. Born in Malaysia, he moved to Singapore at a very young age and joined the trade when he was 15. After his father’s death, he took over as the troupe leader in 2005. The rod puppets belonging to San Chun Long are very valuable to Mr Chew, mostly because of the strong attachment he developed from a young age to them. The puppets have also “witnessed” the ups and downs of Hainanese rod puppet theatre since it was first established in Singapore in the 1920s.

Present Status

One challenge Chinese puppetry faces is the language barrier. Fewer younger Singaporeans speak dialects now. Without an understanding of the dialects used in Chinese puppetry, this art form is now largely limited to the older generation.

The common perception that string puppet theatre is meant for rituals means that few had been willing to sponsor string puppet performances for entertainment. However, various puppet troupes are increasingly performing beyond temple settings and staging secular puppet shows meant for general public, especially tourists and children. Some troupes have also attempted to make modern puppets more adorable to appeal to the younger audience.

Both the Hokkien and Henghua branches of Sin Hoe Ping have helped to revive Chinese puppet theatre in Singapore. In fact, Hokkien puppetry still has a fairly large presence here.

One of the changes appears to be that many puppeteers now perform more spontaneously, with less technical training in puppet manipulation. As secular performances with child-friendly puppets also become more common, a more contemporary arm of Chinese puppetry evolves alongside the traditional one.

References

Reference No.: ICH-008

Date of Inclusion: April 2018; Updated March 2019

References

Chia, Caroline. “‘Negotiation’ between a religious art form and the secular state: Chinese puppet theatre in Singapore and the case study of ‘Sin Hoe Ping’.” Asian Ethnology, 76 (1): 117, 2017.

Chia, Caroline. “Potehi in Singapore, Survival and Change.”, in Kaori Fushiki and Robin Ruizendaal (eds), Potehi: Glove Puppet Theatre in Southeast Asia and Taiwan. Taipei: Taiyuan Publishing, 2015.

Chong, Wing Hong. “Taoist disciple who became master puppeteer.” The Straits Times, September 1988.

Dolby, William. “Origins of Chinese Puppetry.” Bulletin of the School of Oriental and African Studies, University of London, 41 (1): 97–120, 1978.

Fushiki, Kaori and Ruizendaal Robin. Potehi: Glove Puppet Theatre in Southeast Asia and Taiwan, Taipei: Taiyuan Publishing, 2015.