Chinese Calligraphy

Chinese calligraphy, or shufa (书法) — translated literally as “method of writing” — is a means of writing Chinese characters in an aesthetically pleasing manner. This form of artistic expression has a rich history dating back thousands of years. During China’s Tang Dynasty (618-907 CE), calligraphy was considered an important subject at the prestigious Imperial College, and it remained a criterion for the imperial examinations even in the Qing dynasty (1644-1911 CE).

It evolved as an art form in the Song dynasty (960-1279 CE). During that period, poetry writing was combined with visual art practices using the Chinese brush. By that time, it had also become common to place calligraphic couplets at household doors, especially during Chinese New Year. This custom is still popular today, in the same way that calligraphy remains highly esteemed across East Asia.

Geographic Location

Though having originated in China, Chinese calligraphy is practised all over the world today. It is not site-specific, and so can be done in homes, schools, calligraphy centres, community clubs or other settings. Exhibitions, demonstrations, and Chinese calligraphy classes have provided opportunities for people to learn more about the art form.

Communities Involved

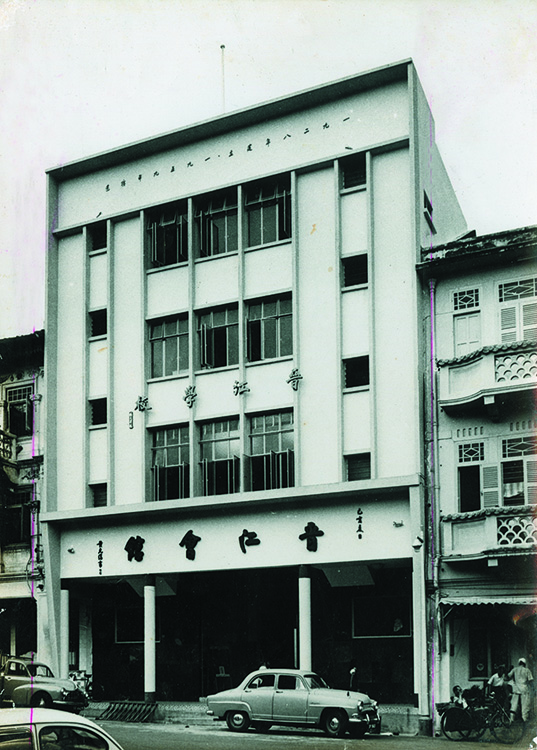

In Singapore, individual calligraphers — both professional and amateur — as well as various organisations are actively involved in the practice. Associations that regularly conduct exhibitions in Chinese calligraphy include the Chinese Calligraphy Society of Singapore (新加坡书法家协会), Molan Art Association (墨澜社) and Shicheng Chinese Calligraphy and Seal-Carving Society (狮城书法篆刻会), to name a few.

The Singapore Hokkien Huay Kuan (福建会馆), Singapore Hui Ann Association (惠安公会), and Singapore Lee Clan General Association (李氏总会) are a few of the many clan associations here that organise calligraphy classes and related activities to promote the art form.

Various community centres organise such classes as well. Basic calligraphy classes are also offered by some schools as an optional enrichment activity.

Associated Social and Cultural Practices

Chinese calligraphy was once regarded as one of the “four arts” a Chinese scholar needed to master in order to be considered accomplished. The other three requirements were qin(a stringed musical instrument), qi(the strategy game weiqior Go), and hua(Chinese painting).

In pre-World War II Singapore, Chinese calligraphy was seen as a practical skill that could be utilised anywhere, be it for writing letters, or for use in auspicious displays in households, signboards, and newspaper advertisements. After the war, however, and especially with the advent of English-language schools from the 1960s onwards, the teaching of Chinese calligraphy waned.

From the 1980s, Chinese calligraphy was revived only as an extra-curricular activity in selected schools or at external centres. Instead of being part of formal education or professional training in art schools, it gradually became an artistic practice among amateurs and retirees.

The art of Chinese calligraphy traditionally includes four main tools and materials known as the “Four Treasures of the Study” (or wen fang si bao, 文房四宝). These comprise the brush, the ink, the paper, and the inkstone. A more recent variation is “hard-pen calligraphy”, developed in the 1900s. This incorporates the use of fountain pens instead of brushes.

Before a practitioner develops his own unique style, he typically masters the art by mimicking well-known calligraphic works from various historic periods. This would require him to acquire the knowledge of one or more forms of script, like zhuan shu (篆书, seal script), li shu (隶书, clerical script), kai shu (楷书, standard script), xing shu (行书, semi-cursive or “action script”) and cao shu (草书, cursive script). Knowing classical Chinese literature also aids the practitioner as he incorporates such text into his practice.

Experience of a Practitioner

Dr Leong Weng Kee an independent artist, who first learned to write with the brush during his early education at a private school in Kim Keat Road. In the 1940s, he studied in Chong Cheng Primary School in the Kampong Glam area, where it was a requirement to write Chinese compositions with a brush. He credits the huaxiao (华校, Chinese-medium schools) of the past for playing a prime role in promoting basic knowledge of calligraphy among the young in Singapore.

The old techniques that he remembers being used to teach beginners calligraphy are miaohong (描红, writing over red characters) and shuanggou (双钩, double outlining). These taught students to trace the shapes of Chinese calligraphic characters with different strokes, and provided the foundation on which Dr Leong could build his skills upon over the years.

Dr Leong explains that each Chinese character is not only a word but also a pictorial representation of its meaning. He says, “Chinese calligraphy is not just a communication tool, it is an artistic expression.” A good piece of calligraphy reflects both a “well-balanced structure” and “skilled brush strokes”. By this, he means that each word is perfectly structured in a pleasing composition, each stroke characterised by smooth, confident vertical and horizontal lines with the brush lifted and dipped at strategic points. He feels this expressiveness in brushstrokes cannot be reproduced as effectively with the use of the less pressure-sensitive fountain pens, as practised in hard-pen Chinese calligraphy.

He adds that mastering Chinese calligraphy is not an overnight process. “It doesn’t just take one or two days, or even one or two years. You need a dozen or even twenty years before you develop even a semblance of your own style.”

He feels that though activities held during festive occasions such as Chinese New Year to promote Chinese calligraphy may stir momentary interest, what really matters is an individual’s passion for this art form. Dr Leong thinks that interest in calligraphy should be developed from young and hopes that calligraphy classes could be introduced in primary schools.

Present Status

Chinese calligraphy continues to be valued by the general population. However, for Chinese calligraphy to be more greatly embraced and practised, Dr Leong feels that “the whole social environment is somewhat instrumental. Singaporeans have to be less utilitarian in their outlook and be open to invest time in learning something that they can’t necessarily earn money from.” Chinese calligraphy continues to be practised by enthusiasts and exhibitions are also held in venues like the Singapore Calligraphy Centre in Waterloo Street.

References

Reference No.: ICH-072

Date of Inclusion: October 2019

References

Tan Siah Kwee. Xinjiapo Shufa Shi 新加坡书法史 (A History of Singapore Calligraphy). Singapore: The Chinese Calligraphy Society of Singapore, 2017.

Wang, Yunkai. “Calligraphy Growing Strong in Singapore 书法在新加坡茁壮成长”. In Pan Guoju (ed.), Xinjiapo Huashe Wushinian 新加坡华社五十年 (50 Years of the Chinese Community in Singapore). Singapore: Global Publishing, pp. 199–210, 2015.

Xie, Guanghui & Chen, Yupei. Xinjiapo Malaixiya Huawen Shufa Bainian Shi 新加坡马来西亚华文书法百年史 (“A Hundred Years in the History of Chinese Calligraphy in Singapore and Malaysia”). Guangzhou: Jinan Daxue Chubanshe, 2013.