Cheongsam Tailoring

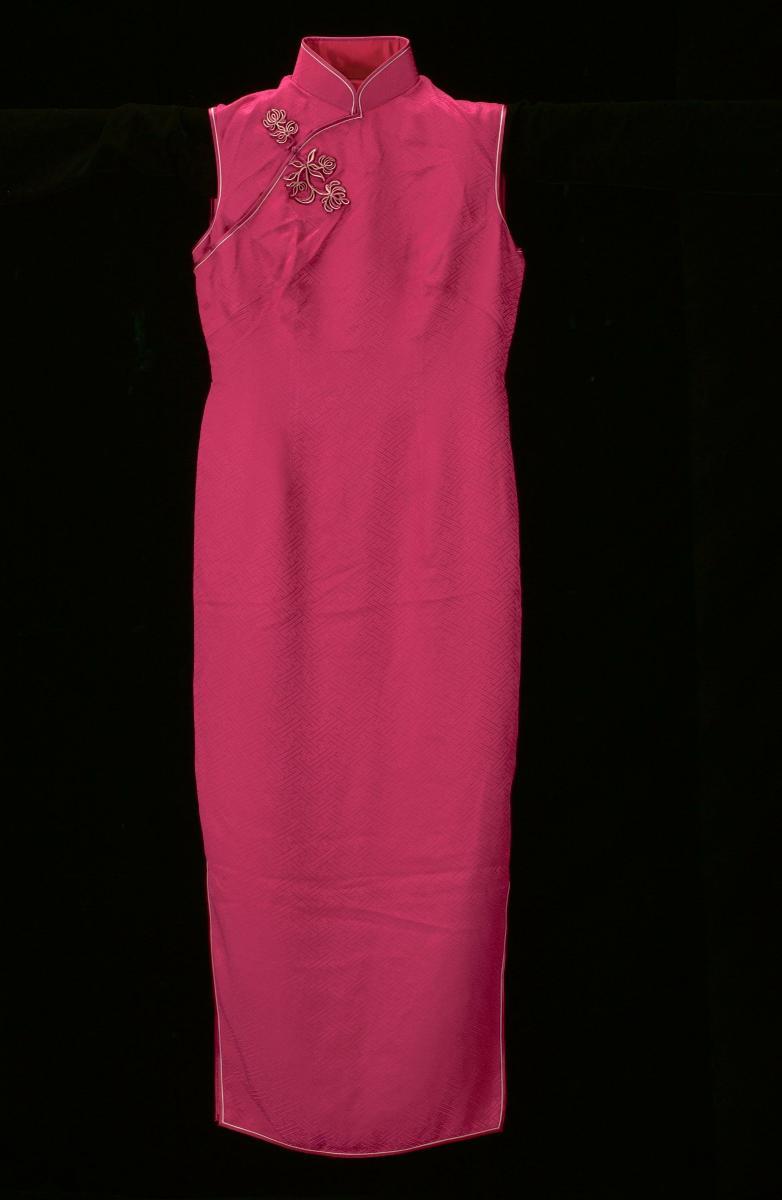

The cheongsam, or qipao (旗袍), is an elegant, form-fitting dress that originated in China. Its classic form is characterised by a high cylindrical collar. An opening, traditionally fastened by knotted buttons, runs diagonally to the right from the middle of the collar to the armpit and then down the dress’s side. The garment usually features side slits at the skirt hem as well.

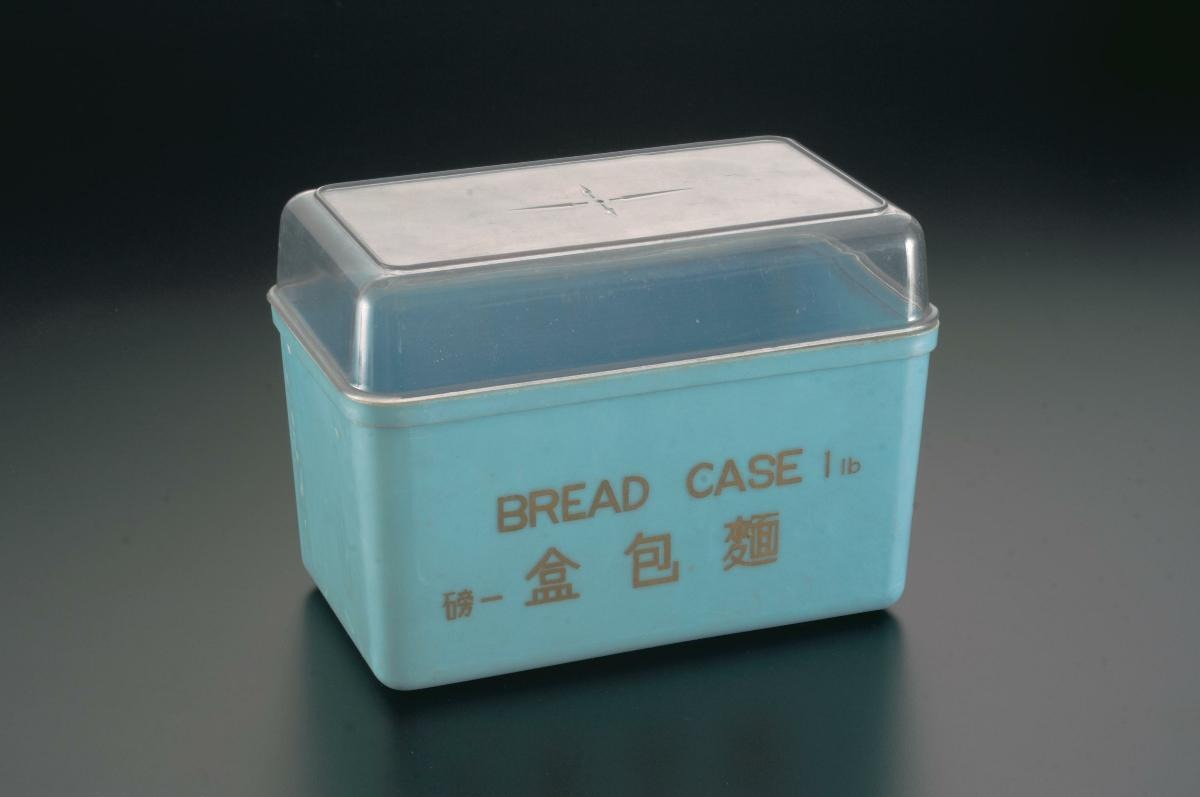

The design is said to have been influenced in the early 20th century by an existing two-piece garment comprising a buttoned long-sleeved jacket and ankle-length pleated skirt or trousers, as well as an outfit known as the changpao that was traditionally worn by men. The cheongsam has continued to evolve with it becoming shorter and more form-fitting over the years. It was popular among affluent or white-collar Chinese women in Singapore up to the 1960s, due in part to the sizable number of tailors offering their services.

Geographic Location

Cheongsams and the tailoring is present in places with Chinese population, including in Singapore.

Communities Involved

In Singapore, Chinese females have been involved in cheongsam over generations. As more female Chinese immigrants came to Singapore after 1900s, the cheongsam became an important identifier of ethnicity and social background. It was popular among working-class women, first with teachers, who saw the garment as a sign of their educational status and modernity.

As more women joined post-war Singapore’s workforce in the 1950s, the cheongsam became acceptable work attire for those employed in offices, commercial firms, and frontline services, and were even worn by women of non-Chinese backgrounds. Cheongsams were also popular among women working in the recreation and entertainment scene. In the 1960s, when television was introduced in Singapore, popular actresses such as Ge Lan and Lin Dai wore and glamourised the cheongsam.

By the 1970s, however, the cheongsam’s popularity waned as the younger generation found the dress too formal, confining, and old-fashioned. Cheongsam tailoring businesses declined, spurred on by apprentices giving up the craft due to the long, irregular working hours and rising business costs. The dress re-emerged in the 1990s, a time when “Asian values” were promoted in Singapore. The cheongsam was seen as a symbol of such values, embodying power dressing.

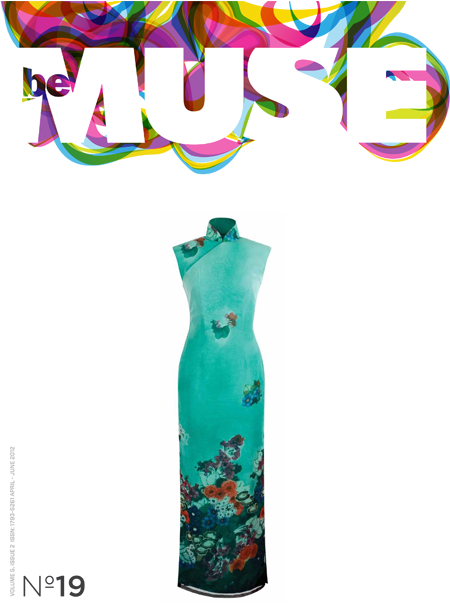

Today, cheongsams are still embraced by women, both Chinese and non-Chinese, for all occasions. Cheongsam tailoring businesses are increasingly catering to evolving modern preferences. It is also popular to wear cheongsam during social or festive events, such as at wedding banquets and during the Chinese New Year. Some cheongsams designs have also incorporated multicultural influences, such as the use of batik.

Associated Social and Cultural Practices

Though much as it has evolved over time, certain elements of the cheongsam – like the high Mandarin collar – remain unchanged.

Sixteen pieces make up the pattern cut-outs of a short-sleeved cheongsam with a front slit. Materials such as silk, satin, velvet, lace, and cotton bearing iconic Chinese motifs such as the flower, butterfly or dragon are typically used. Finished garments could range from exquisite brocades with elaborate embroidery and flamboyant colours, designs of muted sophistication, to plain and humble cuts. Thus, there is a cheongsam to suit any occasion.

Traditionally, the cheongsam is completely handmade, including its buttons. Each knotted button is made from the same fabric as the dress and is named after its shape – “flower”, “butterfly”, and “kumquat”, for instance. They are stiffened with starch, fine wire or, in complicated designs, stuffed with cotton to create the required motif. The knotted button is the product of thousands of years of traditional knotting craft. It is even said to represent the soul of the cheongsam.

Experience of a Practitioner

Madam Li Qiying, originally from Guangxi, China, picked up cheongsam-making from her mother, who had learnt it from Shanghainese teachers. At 9 years old, she began sewing buttons on cheongsams to help her mother. At 10, she stopped schooling and at 13, started making cheongsams. Later, she went to Beijing to further her studies in fashion design. There, she studied under a teacher who specialised in cheongsams and Chinese tunic suits.

After coming to Singapore in 2004, she initially stuck to sewing at home and taking in sewing from factories. But, in 2007, she rented a shop space to do general alterations. To keep alive her cheongsam-making skills, she started making a few of the garments. Her creations were well-received and, thereafter, business took flight.

She says more young people are wearing cheongsams to work, but that they prefer longer and looser fits below the waist, sans slits at the hem, for a more conservative look. Cotton and lace materials are favoured to suit Singapore’s hot weather.

Small as it seems, the simplest knotted button takes about half an hour to make, according to Madam Li. Complicated designs like butterfly-knotted buttons, which involve the turning over and ironing of cloth, can take at least one hour per pair to make.

Another challenging aspect about cheongsam tailoring is the traditional sewing of the “split”, or cha (叉), as it incorporates single or double trimmings into the fabric. Great skill is needed to sew this well, as it affects the way the cheongsam falls. Fabric choice also affects the difficulty of sewing, as thinner materials are harder to sew.

Madam Li does not believe in mass-producing cheongsams. She says mass-produced cheongsams tend to “go out of shape” and the quality and materials used in their making are compromised. “For cheongsams to be pretty, (they have) to be tailor-made...Whether it’s simple, ordinary, cheap or expensive, we make them one by one.”

Present Status

For generations, the cheongsam has been an emblem of power dressing and a statement of one’s cultural identity. Its versatility is evident in the way its style has evolved over the years, with fashion designers continuing to be inspired by it. The garment is still worn today on special occasions such as Chinese New Year and weddings, and even as formal work wear. The practice of tailoring custom-made cheongsams looks here to stay.

References

Reference No.: ICH-042

Date of Inclusion: April 2018; Updated March 2019

References

Chua, Beng Huat. “Postcolonial sites global flows and fashion: A case study of power cheongsams and other clothing styles in modern Singapore”, Postcolonial studies: culture, politics and economy 3(3): 279-292, 2000

Davis, Lindsay. Chinese Women’s Association: 100 Fabulous Years. Singapore: Editions Didier Millet Pte Ltd, 2015.

Lee, Chor Lin and Chung May Khuen. In the mood for cheongsam. Singapore: Editions Dider Millet, 2012.

Lee, Tienny. Dress and Visual Identities of the Nyonyas in the British Straits Settlements; mid ninetheen to early twentieth century. Sydney: University of Sydney, Department of South East Asia Studies, 2016.

Ling, Wessie. “Harmony and Concealment: How Chinese Women Fashioned the Qipao in 1930s China”. In Maureen Daly Goggin Daly (ed.), Material Women, Consuming Desires and Collecting Objects. Ashgate: Farnham, 2009.

National Heritage Board. Costumes Through Time, Singapore. Singapore: National Heritage Board and Fashion Designers Society, 8 October 1993.

Van Roojen, Pepin. Cheongsam. Amsterdam: Pepin Press, 2009.