Bangsawan

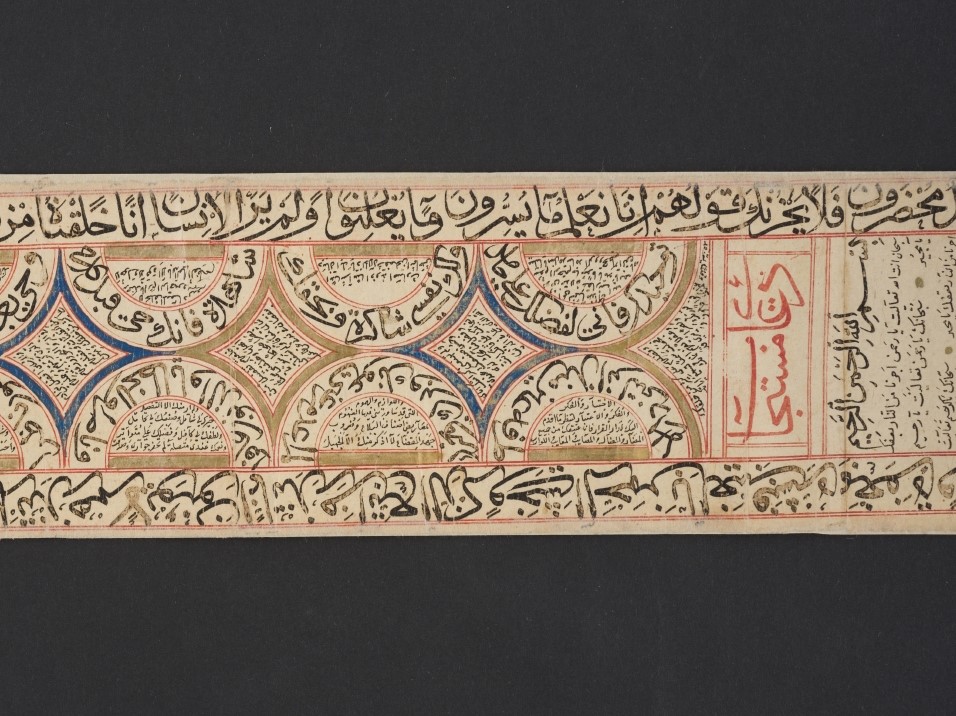

Bangsawan is a form of Malay operatic theatre. Derived from the Malay term for “nobility”, bangsawan focuses its stories predominantly on Malay nobles and royalty. But, it is also multicultural in nature, with plots that are sometimes based on Indian and English stories, and involving performers from diverse ethnicities.

Geographic Location

Bangsawan is indigenous to South-east Asia, and present in places such as Singapore, Malaysia, Thailand and Indonesia. The art form has variations in the different places.

In Singapore, the first performances were held in present-day Kampong Glam, which was a site where various cultural activities took place in the early 20th century, and is believed to be the area which provided the seedbed for bangsawan to develop. In recent years, bangsawan productions have also been staged in venues such as the Victoria Theatre and Concert Hall, and the Esplanade – Theatres on the Bay.

Communities Involved

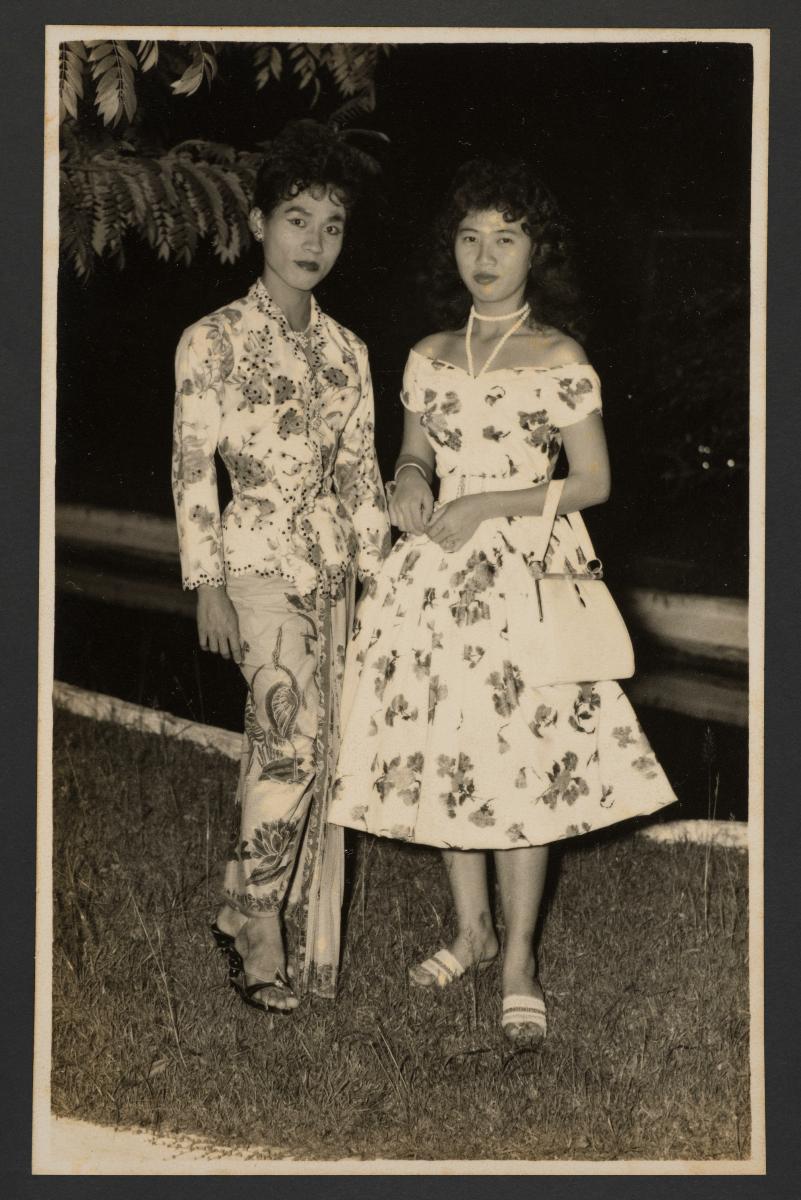

While bangsawan is rooted strongly in Malay culture, neither the productions nor the community supporting it have been exclusively Malay. Audiences in the early 20th century seemed to prefer troupes that showcased elements from different cultures and had actors who could perform various styles and speak different languages. Bangsawan’s extensive repertoire of styles meant it was accessible to more people since there was something for everyone. Bangsawan productions in the 1920s and 30s were also supported by people from the Peranakan Chinese, Jawi Peranakan, and Eurasian communities.

In the past thirty years, a few performance arts troupes and interest groups have worked to revive interest in bangsawan by staging performances and holding classes to introduce the art form to non-practitioners.

Associated Social and Cultural Practices

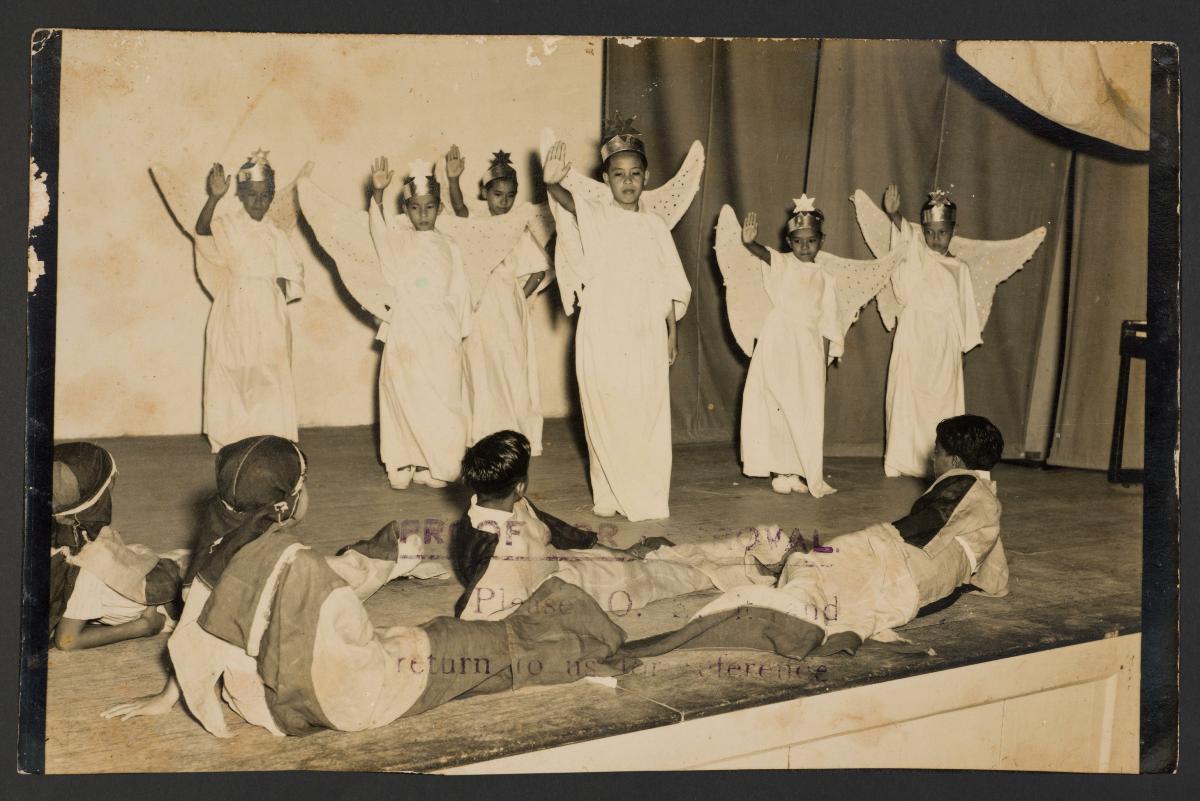

Bangsawan is a theatrical opera that combines storytelling and choreography. Each scene is developed to ensure that the audience understands the story easily. Actors’ dialogues follow a rhythmic pattern, with musicians supporting this type of delivery. The script often makes use of Malay similes and metaphors.

Versatility is a key element of bangsawan, and this is seen in many aspects. Actors have to be proficient in skills like singing, comedy, and martial arts. They have to improvise while playing the role of stock characters such as the orang muda (hero) or rajah (kings), and also be fluent in the dance movements specific to each character. For example, the hero has to portray traits such as courage and gallantry in his performances. The dance styles used are wide-ranging as well, from Malay traditional dances such as the joget to European ones like the foxtrot.

Songs in a bangsawan performance are often designed, and even improvised, to get the most out of a scene. The lagu tarik, also known as a drag song, relies on its melodious nature to amplify melodrama while the lagu hambat or obstructed song is used when the story has to be shortened due to unfavourable conditions, such as rain during an open-air theatre performance. The music is provided by a backing orchestra that draws on Malay, Arabic, Javanese, Indian, and popular European tunes, depending on the background of the story.

The costumes and sets used in bangsawan accentuate the differences between the characters’ social classes. Those representing the nobility typically wear regal attire in bright colours, while characters of a lower social status wear simpler outfits in muted shades. Similarly, furnishings and background paintings tell the audience where the action is taking place: a palace or a common man’s dwellings.

All these different elements have to be woven together delicately to create a bangsawan performance worthy of its majestic nature.

Experience of a Practitioner

Mr Azman, a local practitioner of bangsawan, has been involved in the art form since the early 1980s. He has acted in the bangsawan productions of stories such as Cahaya Bintang (Starlight) as well as classic tales like the Dandan Setia (Faithful Dandan). Mr Azman comes from a family with a history of performing bangsawan – both his late father and his elder sister had acted on stage. He was also mentored by the late Haji Ahmad Arshad (Pak Hamid), the renowned bangsawan playwright.

Mr Azman recounts the difficulties faced by early bangsawan performers who had to develop plays without the aid of scripts, and often had to improvise to ensure that stories from various cultures fit the bangsawan format. Because of the considerable skills that they possessed, prominent bangsawan actors such as those who played the orang muda were highly sought after. Troupes were willing to pay them handsomely and the performers could move to a new troupe if they had a better offer, which Mr Azman compares to the transfer of players between football clubs today.

Present Status

Bangsawan still has a following in Singapore, although it may not be as popular as before. Bangsawan troupes such as Sri Anggerik Bangsawan is still active, while Malay performance arts troupe SRIWANA sometimes produces bangsawan programmes. There have been efforts to revive this art form, such as the Radin Mas-inspired bangsawan based loosely on the folktale of a Javanese princess, that was staged in 2016. But, challenges remain, such as the high costs of production as well as declining interest. Despite these obstacles, the bangsawan community hopes that this art form can be revived so that future generations of Singaporeans can appreciate its cultural and majestic nature for years to come.

References

Reference No.: ICH- 007

Date of Inclusion: April 2018; Updated March 2019

ReferencesBrandon, James R. Theatre in Southeast Asia.Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1967.

Effendi, Samsuddin and Rahmah Bujang. "Bangsawan: Creative Patters in Production." Asian Theatre Journal, 2013.

Sarwar, Ghulam. Panggung Semar: Aspects of traditional Malay Theatre. Petaling Jaya: Tempo Publishing, 1992.

Weintraub, Andrew. "Music and Malayness: Orkes Melayu in Indonesia. 1950-1965." Archipel 79 (1) : 57-78, 2010.