Text by David Chow

Images courtesy of Singapore Art Museum

BeMuse Volume 5 Issue 1 - Jan to Mar 2012

Since the birth of contemporary practice in Singapore – signalled by the formation of The Artists Village, 5th Passage as well as the landmark exhibition, Trimurti from 1988 – artists here have been exploring increasingly diverse mediums of creative work. Performance art, site-specific installations, graphic design and interactive media have become popular alongside new incarnations of painting and sculpture. Future Proof presented artworks by 26 exciting young Singapore artists with innovative and original art practices. Their artistic ventures take place from streets to galleries, their concerns local to geopolitical, their materials both found and acquired. The strong and consistent presence of these young Singapore artists in the local and international contemporary art landscape has enlivened the Singapore creative scene and inspired the birth of numerous other self-taught artists in Singapore.

Presented in galleries, corridors and street sides all at the same time, the exhibition drew from the Singapore Art Museum’s permanent collection and special new commissions, reinforced with artworks from the personal holdings of respective artists, Future Proof offered a measure on the contemporary art practice of Singapore artists today.

The Notion of ‘Place’

Singaporean filmmaker Royston Tan’s documentary Old Places captures distinctive places in Singapore that are close to people’s hearts, so as to preserve memories that are increasingly disappearing from our landscape. “By collecting these images (of old places), it balances the sense of displacement people feel when familiar places disappear”1. As such places are filled with meaning, the loss of many of them in the rapidly evolving Singapore landscape is even more deeply felt by people2.

The notion of ‘place’ is a very powerful one. It is the stage and backdrop to all human activity. Given our culturally constructed lenses and frames, it is part and parcel of human activity, experience and communication. Beyond that, however, in the most deeply seated myths and notions of landscape and place is the idea of rootedness – where ideas of home and belonging, of locality and identity, and of the social dangers of change and modernisation exist3, all being intricately and strongly tied to ‘place’.

The difference between ‘site’ and ‘place’ is that of the quantitative versus the qualitative. Rather than simply measuring the physical world, looking at ‘place’ measures the spiritual, political and moral qualities of a particular area, recording and representing the space and time of how people in that place have lived their lives4.

Landscape is embedded in the practical uses of the physical world as nature and territory. But by further looking at landscape through political and legal contexts, what emerges from specific geographical, social and cultural circumstances is a site for the negotiations of social, economic, and political geographies (of territory, border, exchange), as well as power relationships and subordination. Thus the spatial expression of one living in a particular territory is rooted in subjects such as land and sea, untamed spaces, and urban skylines5.

More than just physical land or the marked territories of a country, the idea of ‘place’ when interlinked with memory, reveals a more abstract quality of a site that could be perceived as its (true) “culture”6. To do so would be to “excavate below our conventional sight-level of the physical to recover the veins of myth and memory that lie beneath the surface” - to reveal the power of social memory in shaping individual and social identities, as well as its presence in the physical world7, 8.

‘Place’ thus becomes the site for the performance and expression of identities: a site for identity to negotiate with social, economic, and political geographies.

Through their works, the artists in Future Proof explored some of the contexts that have shaped both the nation’s identity and their own – visualising, conceptualising, recording and representing the space and time they live in.

Performance of Identity in ‘Place’

In 2005, an exhibition titled islanded was organised by the Institute of Contemporary Art Singapore. It featured 12 artists from different island states, focusing on the anxiety of people living in such states.

As the exhibition curators noted, to be ‘islanded’ was not the result of natural forces, but rather of a complex set of political, social and cultural mechanisms9, often intricately linked to nation building.

Early contemporary Singapore art by artists such as Tang Da Wu explored this, particularly with his influential creation Earthworks in 1980. Through this work, Tang tried to capture Singapore’s rapidly changing social and economic landscapes through representing the drastic physical changes in Ang Mo Kio – a rural site which was rapidly transformed and urbanised into a public housing area – by hanging linen clothes in gullies.

Future sites of contestation and negotiation in the Singapore landscape will be many, but well-supported by her people, proof that the Singapore identity was (and is) in the making and being performed ever more so.

The red brick National Library Building at Stamford Road, for example, was an institution for many. It housed not only Singapore’s first free public library but also countless fond memories. When it had to make way for the Fort Canning Road tunnel leading from Stamford Road to Penang Road, passionate calls were made by Singaporeans to save this red brick building. A letter by Kelvin Wang to The Straits Times’ Forum page on 8 December 1998 sparked off a debate that lasted some seven years. Wang wrote:

“Bras Basah has lost too many unique buildings already, and we should not lose the National Library because it would mean that Singaporeans will not only lose another part of their history, but also a part of what forms their collective memory, which helps make Singapore ‘home’.”10

Today, all that remains of the former red brick building are its “two wretched red pillars standing forlorn”. Support for this former building, however, stands unwavering. And so is the recognition of that point in Singapore’s recent history where a rare moment of civic activism tried to save a landmark building cherished by so many Singaporeans.

One of the few ‘artist village’ enclaves in Singapore, other than The Artist Village in Ulu Sembawang, also had to make way for an economically-driven project, the integrated resort and casino on Sentosa12. What was one of the few tranquil sites in Singapore for artists to creatively practise their craft is now home to hotels, a casino, and a theme park; but not before a group of artists including Milenko Prvacki, David Chan and Max Kong fought to keep the village alive.

The Sea

An island, by definition, is completely surrounded by sea. This characteristic and Singapore’s geographical location have been featured as two key reasons for the island’s development from its origin as a fishing village founded by Sir Stamford Raffles in 1819, to the global port and metropolis it is today. Being an island, Singapore’s true territorial boundaries lie not on land but in our surrounding coastal waters. Such characteristics make the maritime territory a site of negotiation and performance of identity for Singaporeans.

The island of Pedra Branca (white rocks in Portuguese) is one such site, located in the eastern entrance of the Singapore Strait between the Malaysian state of Johor and the Indonesian island of Bintan. In 1980, Singapore lodged a formal protest in response to a map published by Malaysia claiming Pedra Branca. During the trial at the International Court of Justice between the two countries in November 2007, the issue of defining a country’s sovereignty and right to rule were debated heatedly, especially in the vast and indeterminate space of sea territory.

Inside Outside (2005) by Charles Lim attempts to encapsulate this. Lim’s photographs of water border markers taken around Singapore waters over a period of one week represent the real border of the nation, despite water around and under it flowing in and out. Especially for an island state, the defining boundaries of the nation’s territory out at sea, he puts forth, does not just signal where its sovereignty ends – it also denotes the border that represents the line between belonging and foreignness; and the ever changing ebb and flow, too, of the nature of identity that is constantly in a state of flux.

Charles Lim, Inside Outside, 2005, Photographs & ship radio connection, Variable dimension, Artist Collection.

Charles Lim, Inside Outside, 2005, Photographs & ship radio connection, Variable dimension, Artist Collection.

Image courtesy of Charles Lim.

Displaced (2003) by Francis Ng, is a set of photographic prints of water taken up close, abstract and seemingly universal, focusing on its relationship with the horizon. The photographs were taken at cardinal points in Singapore, with the artist immersing himself in water to capture each shot. The fluidity of one’s relationship with the surroundings, occasionally with the threat of being engulfed, similarly puts forth the tension, fragility and sometimes confrontation of one’s ever evolving identity and place in the world.

The City

Another site of negotiation is the city itself. Developed rapidly since the nation’s independence in 1965, the swift urbanisation and modernisation of Singapore have transformed her physical landscape from kampong villages into a vast concrete jungle of imposing high-rise modernist architecture. Taking place over several decades, this transformation – like many modern cities today – has proven to be traumatic to the city’s inhabitants. Even after the dust settles and the skyscrapers take over the landscape, this site of negotiation becomes even more contested14.

The newly designated Marina Bay district, where the skyline is dominated by the distinctive shapes of the Singapore Flyer and Marina Bay Sands integrated resort, adds to the Singapore skyline that already boasts of symbols of economic success such as the banking and financial centres. The Marina Bay Sands and the Singapore Flyer have also become sites of negotiation for the Singapore identity, with the pursuit of economic agenda and spirit of pragmatism running up against the moral and the social15, to the point of some Singaporeans comparing this to giving up the Singapore soul and moral fabric16, 17. The debate was fierce and heated, with the focus on bringing in tourists and high net worth individuals to boost the economy dominating all other arguments. If anything, the issue showed a newfound spirit of expressing one’s identity and place at the national level, which were acknowledged by journalists and ministers alike18.

Chun Kaifeng’s sculptures ¥ ¤ $ (2010) and The Ride of a Lifetime! (2010) are expressions of the heated debates surrounding this new entertainment district in Singapore. ¥ ¤ $, with its currency symbols, spells out the chorus of anticipation of money to be earned. And the paint splashed on its back is not unlike the marks made by loan sharks on the doors for their defaulting borrowers. Instead of the thrill and joy associated with most amusement park rides, The Ride of a Lifetime! gives the impression of a prison and a sense of melancholy. The monochromatic models – while deliberately made to be reminiscent of toys and playthings from childhood – contain rather sharp social critique, conveying the strong need for freedom and individuality in a dispassionate society.

Playing with the notions of truth and what the eye really sees is what Donna Ong’s installation, Crystal City (2009), is about. The installation, made up of inverted everyday glassware, is magically transformed into a city skyline, a metaphor for great cities like London and New York where anyone with a dream ‘can make it big’. This beauty, however, comes with fragility and danger as it can all crash quite easily and quickly.

Donna Ong, Crystal City, 2009. Glassware, Variable Dimensions, Artist Collection.

Donna Ong, Crystal City, 2009. Glassware, Variable Dimensions, Artist Collection.

Image courtesy of Osage Gallery Ltd.

:phunk studio’s Eccentric City: Rise and Fall (2010) likewise comments on this fragility of cities, as well as the aspirations and ambitions they are built on.

:phunk Studio (in collaboration with Keiichi Tanaami), Eccentric City: Rise and Fall, 2010, Tatebanko paper box structurs with video installation, Variable dimensions, Singapore Art Museum Collection.

:phunk Studio (in collaboration with Keiichi Tanaami), Eccentric City: Rise and Fall, 2010, Tatebanko paper box structurs with video installation, Variable dimensions, Singapore Art Museum Collection.

Image courtesy of Todd Beltz Photography.

The Decline of Western Civilization (After Penelope Spheeris) (2010) by Gerald Leow, in addition, questions what authentic culture is in a synthetic and constantly evolving world.

Nature

Describing Singapore’s pristine orderliness and highly controlled state, many – including government officials and bodies – have used the metaphor of the well-tended garden versus the wild rainforest, with the bonsai plant often being used as the ideal state to reach towards. Kwok Kian Woon’s essay on The Bonsai and the Rainforest: Reflections on Culture and Cultural Policy in Singapore noted the price for this order and structure – “social disciplining through a system of policing and punishment”19. Just as how Singapore’s luxuriant greenery in the urban landscape is “no accident”, neither is her success today: “A good gardener, with all good intentions, curbs the growth of weeds and tends to the health of the plants; in some cases to protect saplings from the elements.”

The physical, natural landscape (on the decline in Singapore) has come to represent the tussle between an organic situation versus one that is state-controlled and pruned. The lush, diverse (and wild) rainforests of the tropics (used as a metaphor for multiculturalism by the late Kuo Pao Kun) contrast against the bonsai, which is the “end product of Will versus Nature” – the product of a controlled growth to represent an ideal aesthetic view of nature20. Amid the orderly, nature and the wild outdoors has become a site for Singaporeans to express themselves against the structured concrete garden they live in, even if it is filled with creepy crawlies and wild things.

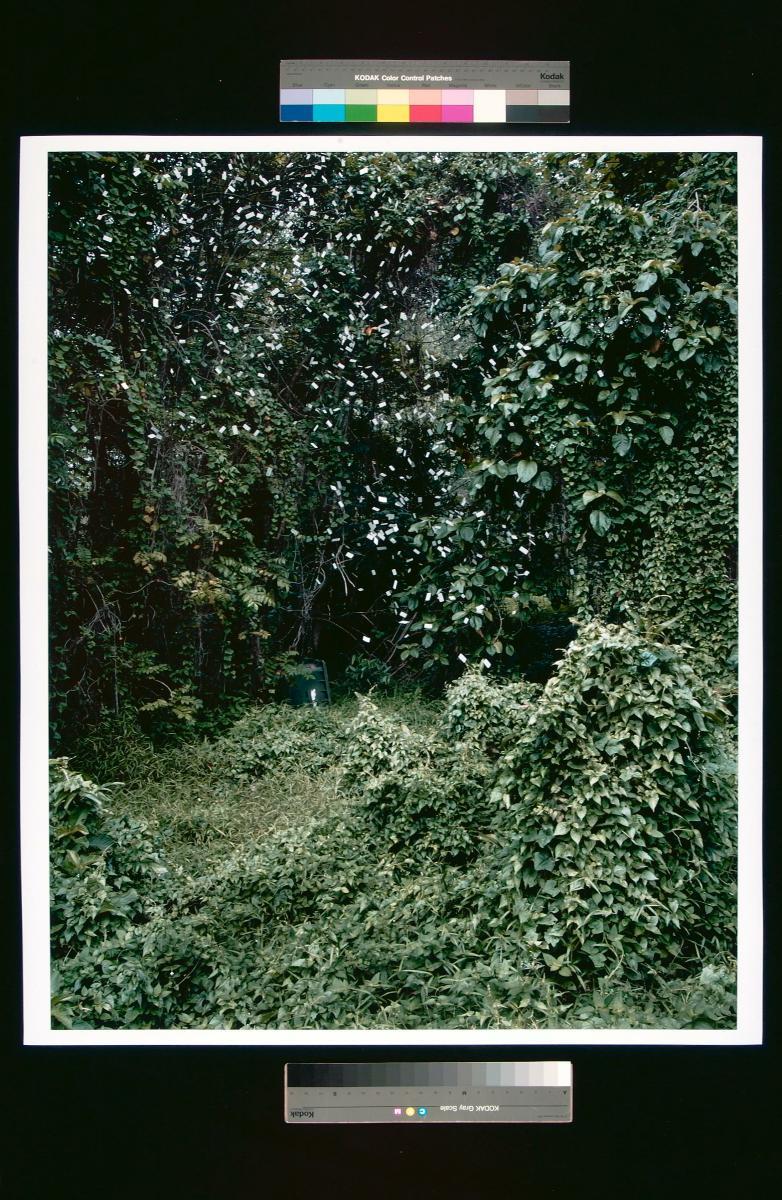

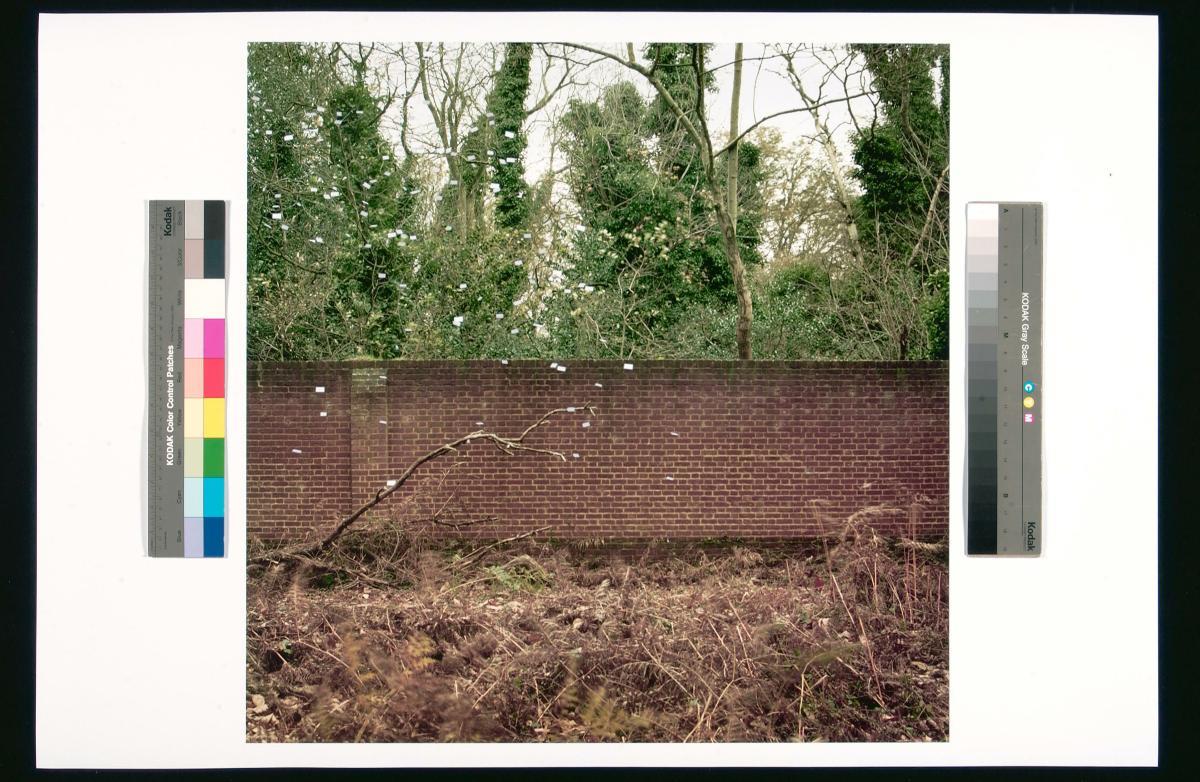

The accidental and spontaneity in the wild can be seen in Ang Soo Koon’s YOUR LOVE IS LIKE A CHUNK OF GOLD (2011) and Melissa Tan’s Under The Blanket of Bedrock (2011). Both works speak of events that happen out of chance, transforming the everyday into something extraordinary. Tan’s paper sculptures speak of how undue pressure can transform rocks into crystals; while something comforting and familiar like bread becomes the unusual site for growth of crystals in Ang’s bread and crystal sculptures. But the wild does hold its horrors for those brought up in a well-manicured bonsai garden, as Ang’s work, along with Genevieve Chua’s After The Flood (2010) series of photographs, convey. The spontaneous growth of crystals on bread is sharp and menacing, no matter its beauty; while Chua’s hand-painted photographs of secondary forest sites21 in Singapore conveys the fear of the unknown beneath the surface and what lies beyond the manicured lawn.

Genevieve Chua, After the Flood #10, #11, #12, 2010, Hand-coloured photographs 52 x 231cm,

Genevieve Chua, After the Flood #10, #11, #12, 2010, Hand-coloured photographs 52 x 231cm,

Singapore Art Museum Collection.

Genevieve Chua, After the Flood #1, 2010, Hand-coloured photographs, 52 x 77 cm,

Genevieve Chua, After the Flood #1, 2010, Hand-coloured photographs, 52 x 77 cm,

Singapore Art Museum Collection.

Beyond Documenting and Representing

The works by the artists in Future Proof went beyond merely documenting and representing. By taking measure of the world rather than just measuring it, these artists have tried to include the remembered, the imagined, and the contemplated; capturing the spiritual, political, moral and social elements of identity.

David Chew is Assistant Curator, Singapore Art Museum