Text by Alvin Chua

MuseSG Volume 8 Issue 3 - Oct to Dec 2015

For centuries, people have shaped the singapore river with legends, stories and accounts ranging from the everyday to the fantastic, and in turn had their memories shaped by the river. The singapore river walk organically ties these elements together for an unforgettable experience of the river where it all started.

The question has been mused upon before, but remains pertinent. If the Singapore River could speak, what stories might it tell? Of the ancient majesty of Temasek, the earliest travellers from across the globe, the flocks of trading ships or the multitudes of immigrants looking to build a better life in nascent nineteenth-century Singapore?

The river has always fired the imagination: From the Orang Laut, venerating a rock in the river’s mouth shaped like a swordfish to avert misfortune when navigating the treacherous waters, to the enduring mystery of the yet-to-be deciphered Singapore Stone, through to the river’s renewal and redevelopment in the 1980s, symbolising the will and progress of modern Singapore.

In this light, the Singapore River Walk by National Heritage Board, launched on October 6 in 2015, is simply a manifestation of the ways in which we celebrate the river.

The trading settlement of Temasek, existent by the fourteenth century and attested to in Chinese and Javanese accounts as well as the Sejarah Melayu (Malay Annals), was located around the Singapore River. With its centuries-deep history, the river is archaeologically one of the richest areas on the island.

The latest excavation, conducted in 2015, found imperial-grade porcelain from the Chinese Ming Dynasty (1368 to 1644), artefacts from the earlier Song (960 to 1279) and Yuan (1271 to 1368) dynasties, Buddhist figurines and gold coins from regional polities.

In 1819, the British landed on the south bank of the river and founded a trading post, which grew into a settlement and gradually into the city of modern Singapore. The earliest British settlement paralleled the boundaries of old Temasek, a point noted by the second colonial Resident, John Crawfurd, as he explored the crumbling ancient city walls still evident in 1822.

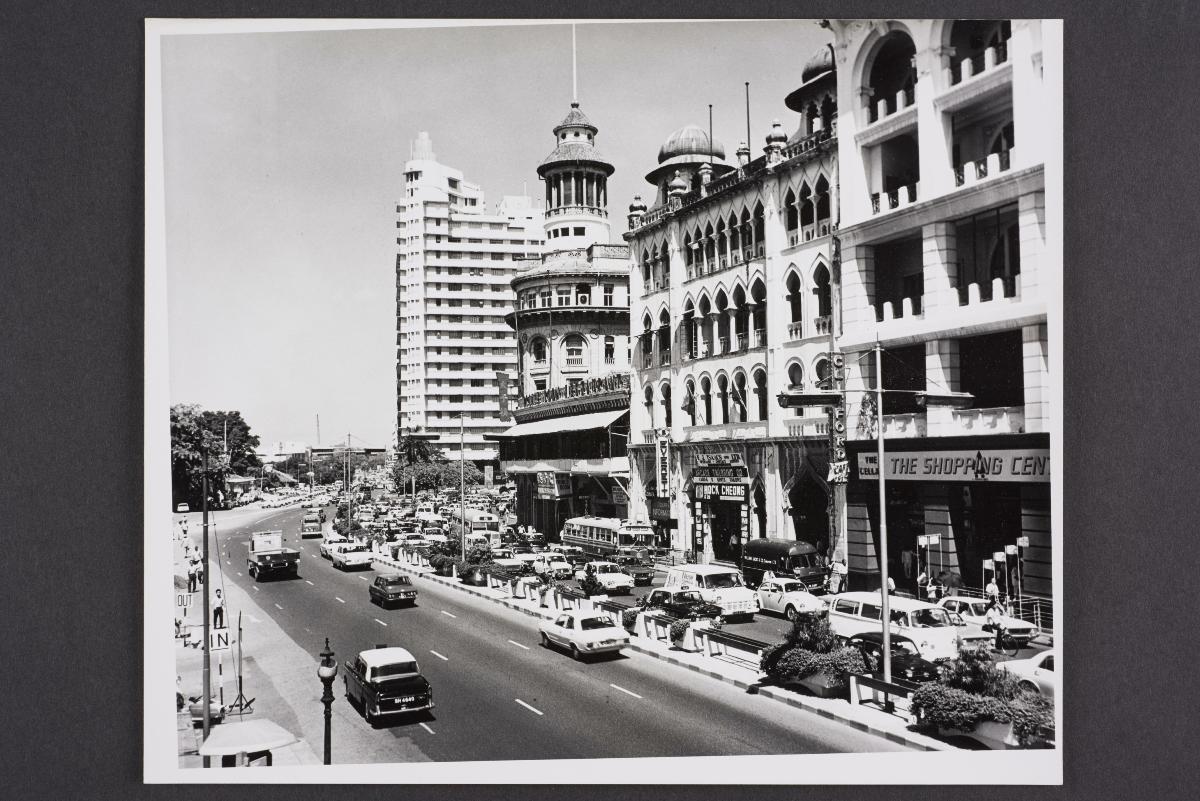

Collyer Quay

Collection of National Museum of Singapore.

In early colonial Singapore, the Collyer Quay area was something of an afterthought. The city centre was further up at the Singapore River and Raffles Place where trading houses, godowns and merchants clustered around the diverse goods ferried in by visiting vessels. Defined in relation to this hive of trading activity, Collyer Quay was a shoreline known in Hokkien as Tho kho au (Behind the godowns).

That all changed after 1864, when the shore was reclaimed and a seawall built even as the Singapore River was becoming congested with boat traffic. Within a few years, Collyer Quay was studded with shophouses and trading offices, out of which merchants scanned the sea for arriving ships with telescopes. The quay, named after Colonel George Chancellor Collyer of the Madras Engineers, was also the first sight of Singapore many immigrants took in from aboard their ships.

Kwan Yue Keng Collection, courtesy of National Archives of Singapore.

This paved the way for development on a grander scale in the early twentieth century, as neoclassical commercial buildings grew in tandem with the tides of commerce. Author and historian Julian Davison remembers: “Here were 1920s blockbusters: Ocean Building, the Hongkong and Shanghai Bank, Union Building and the Fullerton Building, so mammoth because of their cutting edge, lighter reinforced concrete frames and artificial stone cladding. Brilliant from afar was the bank’s cathedral glass, where the female figure of Commerce reigned over ships... Flanking either end, the skyscrapers of Asia Insurance Building and the Bank of China were gigantic legs soaring to the clouds...” These developments presented an imposing waterfront vanguard and drew comparisons with Shanghai’s well-known Bund.

Today, colonial-era buildings that survived include the Fullerton Building (the former General Post Office, once “the most important post office in the east”, according to the Polish writer Joseph Conrad) and the former Asia Insurance Building.

In Collyer Quay, areas bestowed with conservation status today are Clifford Pier, Customs House, and Change Alley Aerial Plaza, which connects the pier area with Raffles Place.

Clifford Pier and Customs House

Collection of National Museum of Singapore.

As a gateway for travellers and sailors, Clifford Pier was as colourful a place as you’d expect. Opened in 1933 to replace Johnston’s Pier (constructed in 1856), Clifford Pier continued the tradition of being lit with red beacons, as was the case with the previous pier.

This earned the pier and the surrounding area the colloquial name of Ang teng (red lamp in Hokkien) and equivalent names in Malay and Cantonese. The column-free Passenger Hall of the pier features Art Deco detailing, including ribbon-like arched trusses on the roof and stylised sunrays on the entrance arch.

A multitude of boats including tongkangs, twakows, jongs, sampans, bumboats and ferries thronged Clifford Pier, taking passengers to ocean-going vessels further offshore, other coastal parts of Singapore or to nearby islands. Shipping and insurance agents, suppliers, sailors and their families, as well as the call girls euphemistically referred to as ‘Coca-Cola girls’, also made their way onto ships via Clifford Pier.

This made for a bustling atmosphere, with stalls where coffee and teh tarik could be had for 10 cents and where your sup kambing might have been seasoned with illicit ganja.

Magdalene Boon remembers: “Sitting on a bench at Clifford Pier, watching the embarking and disembarking of human flotsam and jetsam, from the ever-busy sampans [and] motor launches, was the highlight of the week for me. I love the smell of the sea and listening to all the foreign tongues wagging accompanied by the frantic hand gestures. [It] never [failed] to amaze me [how] people communicate, be it illiterate or not!”

Until the 1970s, koleks and other traditional watercraft converged on Clifford Pier during festive occasions for regattas of boat races, displays of sailing skills and other games. Piloted by villagers from Pasir Panjang and outlying islands including Pulau Seking and Pulau Semakau, these boats and their adroit handlers represented a maritime heritage that stretched back centuries.

Ismail recalls: “There were so many types of different [handmade] Malay wooden boats all skillfully carved and painted with bright colours from the Southern Islands and even the Indonesian islands too. There was much rivalry!”

Next to Clifford Pier is Customs House, where the 300-strong Harbour Division of the Customs Department once kept watch over Singapore’s waterfront. From here, officers locked on to ship-to-shore smuggling of dutiable goods such as liquor and tobacco, and contraband including narcotics.

Of a more sinister nature was human trafficking — Geraldene Lowe remembered Customs officers telling stories of how “sampans would glide into Clifford Pier in the dead of night with special cargo — hot items were opium and girls!” To intercept the smugglers, Customs officers would patrol the waters with speedboats and launches.

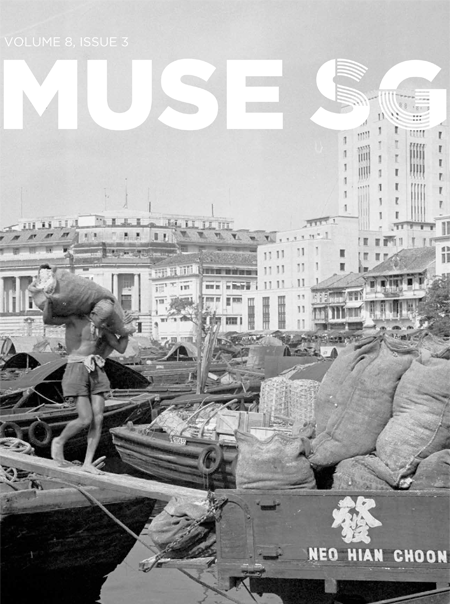

Boat Quay

Collection of National Museum of Singapore.

Boat Quay was the vital artery that kept the famed entrepot trade of early Singapore owing, but things could have turned out very differently if the first British Resident William Farquhar had had his way. Farquhar favoured Kampong Glam for the location of the settlement’s business district, while Sir Stamford Raffles was determined to site the district around the Singapore River, even though most of the land there was swamp, unusable without major reclamation.

Raffles won the day in the debate, and what was to become Boat Quay and Raffles Place formed the site of Singapore’s first land reclamation project between 1822 and 1823. Labourers were paid one rupee a day to level the small hills, on which a number of huts occupied by Chinese planters stood, and fill in the surrounding swampland. The earth from the levelled hills was also used to create embankments around the river, creating Boat Quay, while the land formerly occupied by the hills became Commercial Square and later Raffles Place.

The riverine trade enabled by the development of Boat Quay grew rapidly, spawning evocative place names such as the crescent-shaped ‘Belly of the Carp’ stretch near the river mouth, and early merchant Alexander Laurie Johnston’s Tanjong Tangkap, advantageously located to snap up the most lucrative goods.

Raffles’ declaration of Singapore as a free port saw junks from China, Siam and Indochina arriving with silk, porcelain, rice and opium, while prahus from the Indonesian islands hauled in coffee, spices and gold dust, their merchandise displayed from the sides of their ships to attract the gaze of the merchants in their shophouses and godowns along Boat Quay. The captains made the trip home laden with ironware, opium, steel, guns, cotton and other goods.

Reminiscing about his childhood in the 1950s, Chia Hearn Kok says: “When the tide of the Singapore River was at its highest...you would find me joining the many boys playing in the flooded streets and swimming in the river. We would be in our short pants and bare-bodied...our heads were always above water because of the stench from the animal and human waste and the rubbish. One of our favourite antics was to catch a ride to the Elgin Bridge on the heavily loaded tongkangs [vessels] that plied the river by climbing on to the rubber tyres on their sides.”

Jenny Lum remembers a typical scene of the 1960s: “As my dad was a spice and rice merchant, we lived in Synagogue Street shophouses that have now all been demolished. When the goods arrived in the big tongkang, the head of coolies called the kepala will put a long wooden plank against the tongkang and the coolies will walk up the plank one at a time with a piece of cloth cushioning their shoulder and carry down one gunny sack at a time...they were being paid on the number of sacks cleared.”

Boat Quay’s days of river trade ended in the 1980s, and the river underwent an epic clean-up that involved multiple government agencies and the personal intervention of our founding Prime Minister Lee Kuan Yew. The river and its surrounding areas had been polluted from the days of colonial Singapore. Perhaps the earliest clean-up had occurred when Farquhar ordered the removal of hundreds of human skulls, the remains of the victims of ancient piracy, from the beaches.

By the 1980s, the waterway was choked with refuse, dead animals, food and industrial waste, with the inevitable accompanying stench. The 10-year clean-up saw the removal of pollutive trades around the river from Boat Quay to Robertson Quay, dredging of the banks and riverbed, and the clearance of tonnes of rubbish. Pre-war shophouses were conserved and Boat Quay is today a dining and nightlife destination.

Raffles Place, Change Alley and Market Street

Raffles Place stands today as the heart of Singapore’s financial district, a towering sweep of steel and glass monuments to the power of commerce. Known as Commercial Square before its renaming to honour Raffles in 1858, the area quickly assumed its role as a business hub, where merchants and ship captains flocked to for news, business intelligence and gossip.

As the commercial stakes grew ever higher, so did the buildings of offices, company headquarters and banks. They reach upwards, evolving into the familiar skyscrapers of the present. Some of the renowned buildings of the past included the Chartered Bank Building, where the Standard Chartered Bank Building now stands, the Mercantile Bank on the site of today’s Raffles Place Mass Rapid Transit (MRT) station, and the United Overseas Bank where UOB Centre currently is.

Raffles Place also catered to retail customers. Household name department stores Robinson’s and John Little both started here, while jewellers BP de Silva, textiler Gian Singh and the Honeyland Milk Bar were well-patronised. Paul Kuah recalls: “My siblings used to bring me down to Raffles Place in the 1960s to shop at Robinson’s and John Little. In those days, it was always a high point in my life and I recall the old Chartered Bank building, with the friendly Sikh security guard standing outside during the day and who would sleep on his charpoy in front of the bank’s door by night.”

Courtesy of Singapore Press Holdings Limited.

Those were mainly upmarket establishments that stocked goods for European tastes. Away from the department stores, a bustling bazaar could be found at Change Alley between Raffles Place and Collyer Quay, with shops that thrived on bargaining. These drew locals, tourists and sailors, among others, with their diverse array of goods.

Courtesy of Singapore Press Holdings Limited.

From the early 1800s, Market Street and Chulia Street held a significant Indian presence with migrants establishing trading firms, shops of all stripes, and eateries. The many kittangi (warehouse shops owned by the merchant financier Chettiars) on Market Street gained it the Tamil name of Chetty theruvu (Chettiar’s Street).

A Multi-faceted Walk

These storied sites are just a taste of the many locations to explore around the Singapore River. Included in the river walk are others like Clarke Quay with its former canneries, ice houses and godowns owned by towkays (wealthy businessmen) like Tan Tye and “Whampoa” Hoo Ah Kay. The trail also features the River House, one of only two traditional Chinese houses remaining in Singapore, and the former Thong Chai Medical Institution, where free medical treatment saved the lives of thousands of coolies.

The bridges that span the river, including Singapore’s oldest Cavenagh Bridge, paint a picture of changing times in their own right and warrant a visit. The walk also takes in Masjid Omar Kampong Melaka, the oldest mosque in Singapore, and Tan Si Chong Su Temple, which used to face the former river island of Pulau Saigon.

Explore these locales on the Singapore River Walk to encounter the lesser-known, but equally fascinating, places along the Singapore River, and you might just uncover another facet of an ever-evolving story.

The Singapore River Walk is adopted by American Express.