Text and photos by Carolyn Lim

MuseSG Volume 8 Issue 2 – Jul to Sep 2015

Anyone who tires of the towering glass-steel offices at Raffles City, or the shop-till-you-drop malls along tree-lined orchard road, can head to the west of Singapore and explore a hidden cultural treasure: a dragon kiln. Tucked away at the western end of the island, next to the Nanyang Technological University as of 2015, there are not one but two septuagenarian dragon kilns that transport visitors back in time to a once-thriving pottery industry in Singapore. In the early 1960s, there were about 10 kilns in Jurong producing functional wares, such as earthenware jars and latex cups. The kilns were located in Jurong because of the area’s white sedimentary clay, which is well-suited for the production of these wares.

The Early Pottery Industry

From the 1950s to the early 1990s, dragon kilns were central to the pottery industry when earthenware pots were produced using methods such as coiling, throwing and plaster moulding. Other utilitarian wares, such as latex cups for the rubber plantations, and ceramic souvenirs were also red in these kilns. However, the pottery industry declined, and by the mid-1990s, with the demolition of the Sam Mui Kuang dragon kiln at the Jalan Hwi Yoh, the two other kilns in Jurong — the Thow Kwang and Guan Huat dragon kilns — ceased commercial production. Thow Kwang changed its business model to the import and export of ceramics. The “dragons” went into a slumber.

Thow Kwang Dragon Kiln

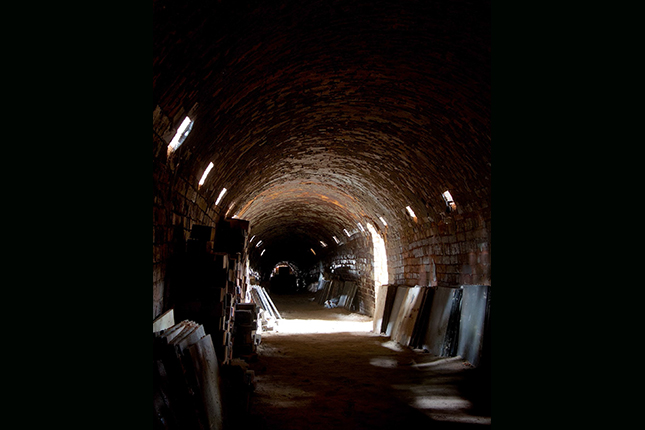

Built in the 1940s, Thow Kwang Dragon Kiln is one of only two surviving kilns in Singapore. The other kiln, Guan Huat Dragon Kiln, is located a stone’s throw away. The dragon kiln (long yao in Mandarin), is a long hollow semi-circular tunnel made of bricks, and resembles the body of the mythical beast. The kiln was built on a sloping terrain to take advantage of the updraft during the ring process.

The Thow Kwang Dragon Kiln is less than a metre wide in the front chambers, and widens to about two metres at the back. At the back of the kiln is a nine-hole brick damper wall, where the smoke and heat escape via a chimney. At the sides, circular humps of bricks spaced at intervals along the kiln’s length support the kiln structure. Visitors enter the 27-metre long kiln through one of the two arched doorways. The doorways are lined with bricks with names like Nanyang, Bee Kiow and Jurong — reminders of Singapore’s past when factories produced bricks for local use. Alongside the kiln are 17 pairs of stoke holes, where wood is added and the firers monitor the temperature inside during the ring process.

Firing the Dragon

A wood ring can take from 25 to 36 hours or more to complete, and this does not include the time needed to pack and load the pieces in the kiln. Why then would anyone want to use this traditional method to fire clay pieces, when today’s commercial electric and gas kilns require much less time and effort?

Many potters yearn for the unique combination of wood ash and salt on their pieces, which gives them a one-of-a-kind result. When using a wood kiln, potters rarely get pieces that are the same. The unpredictability and uncertainty of not knowing how the pieces will turn out gives potters an artistic edge. It is also an experiential process — perhaps potters experience a feeling of being transported to the past when they see the burning wood and the glowing flames licking the clay pieces.

Indeed, this unique wood ring experience is achieved only through great effort. Work begins long before the ring. Hours of preparation are needed to set up the kiln shelves and load the pieces into the kiln. Each piece is carried into the kiln and carefully placed on the kiln shelves. The pieces are strategically arranged to ensure a smooth flow of heat and fire through the kiln. Once all the pieces are packed, the stoke holes and doorways are sealed, and the kiln is ready for ring.

A wood ring usually begins in the morning with offerings and prayers at the fire box. Sticks of wood are thrown into the fire box to feed the “dragon”, and the temperature is slowly raised. As day turns to night, the temperature rises and the heat gets more intense.

Standing in front of the kiln, a person may be overwhelmed by the heat, the glowing flames and the crackling of burning wood in the kiln. The firers, working in shifts, are all flushed and sweaty — but the work only gets tougher from here. When the temperature in the kiln finally reaches 800 to 1,000 degrees Celsius, lots more effort and wood are needed to feed the kiln. There are anxious moments when the temperature drops instead of going up, and the firers have to feed more wood into the fire box. Everyone watches the thermocouple readings eagerly to see if the temperature will rise again.

After 12 hours or more, and when the temperature at the fire box reaches 1,250 degrees Celsius, the front pit is sealed — amid shouts of relief and joy — and the firers move to the stoke holes on both sides of the kiln. The process of feeding the kiln continues. Through the stoke holes, the firers look for the pyrometric cones which bend at a particular temperature, signalling to the firers to move to the next pair of stoke holes. Almost always, salt is thrown into the kiln at this stage. Salt reacts with the silica in the clay body, and this chemical reaction forms an attractive glaze. This continues until each chamber in the kiln is fed. When the last stoke holes are sealed, the remaining glowing embers are left to extinguish as the dragon draws its final breath and is left to cool. The Thow Kwang dragon kiln is red about two to three times a year. To witness or participate in a wood ring process is truly an unforgettable experience.

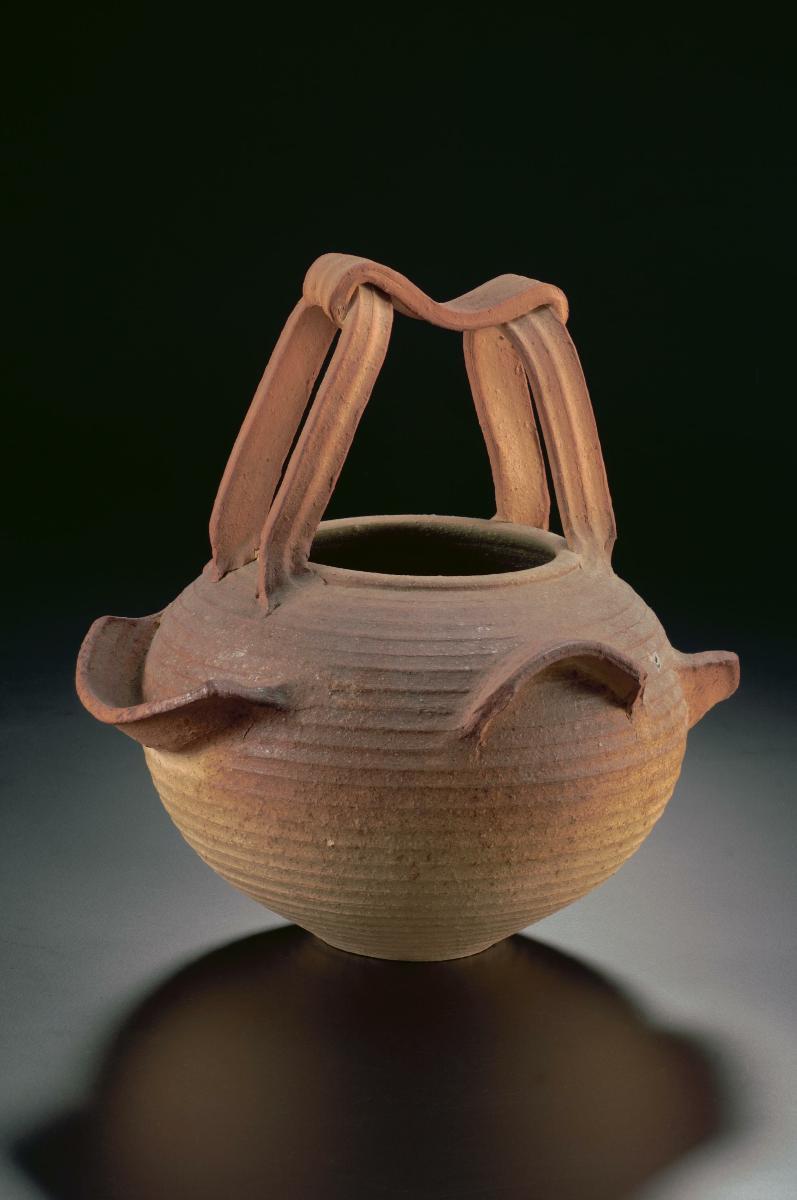

One-of-a-kind Wood-fired Pieces

The kiln is left to cool, and days later the unpacking begins. This is often a moment of apprehension and curiosity as the potters can finally see the pieces. Each piece is knocked loose from the kiln shelves and carried out to be examined. The uniqueness of a wood-fired piece results from the combination of wood ash and salt that coat the pieces. It is unpredictable, erratic and what gives a wood-fired pot its uniqueness and beauty.

Weekend Clay Experience

On weekends, Thow Kwang dragon kiln is a bustle of activity. In one area, a group of potters are throwing or glazing their work; in another, children and adults are trying their hands at being potters. For a small fee, anyone can have a hands-on experience working with clay, making and ring a small piece to bring home. Sometimes, a throwing demonstration on the kicking wheel by one of the potters can be seen.

Interested to know more about wood-firing? Now there’s a free interactive app, DragonFire Singapore, supported by the NHB Grant Scheme. It gives a close-up look at woodfiring in action, available for iPad on iTunes. Download it here.

Check out Thow Kwang’s Facebook page for a schedule of its weekend workshops.

Thow Kwang Dragon Kiln, 85 Lorong Tawas, S639823 Guan Huat Dragon Kiln, 97 Lorong Tawas, S639824

If you would like to learn more about the NHB Grant Scheme, click here or email NHB_heritagegrants@nhb.gov.sg