TL;DR

Often tucked away from sight, informal shrines, sometimes honouring deities from multiple religions in a single altar, lend colour — and spirituality — to the island’s urban environs.

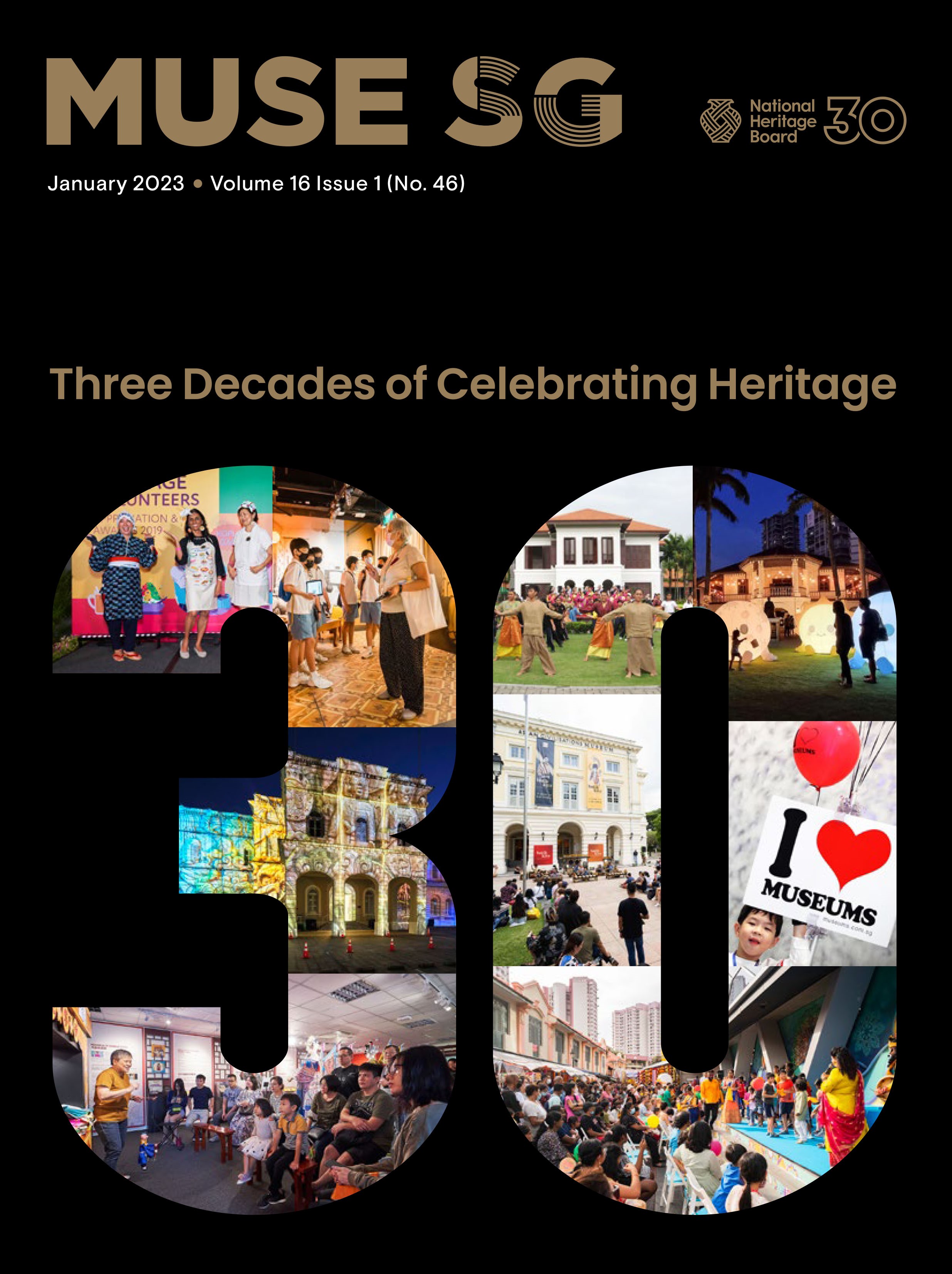

MUSE SG January 2023

Text by Dr Sujatha Arundathi Meegama, The Courtauld Institute of Art, UK; Dr Owen Noel Newton Fernando, School of Computer Science and Engineering, Nanyang Technological University; Hedren Sum Wai Yuan, NUS Libraries

Read the full MUSE SG January 2023

It is not unusual to come across diverse places of worship in multiethnic and multireligious Singapore. Some are humble, like Masjid Hang Jebat, tucked away in leafy suburban surroundings, while others, such as Sultan Mosque and Central Sikh Temple, are majestic structures that occupy sprawling grounds. These places of worship sit on land plots that the government has designated for religious purposes. In a land-scarce country like Singapore, the use of public space is highly regulated.1

But hidden in the nooks and crannies of public and secular spaces are some small but important shrines that have mushroomed, and sometimes been forgotten, over time. These ‘wayside shrines’ are usually makeshift altars that occupy unofficial spaces in the urban environment. They may be found practically anywhere—along roadside and railway tracks, at bus stops, carparks, loading docks, construction sites, factories, under expressways, in shopping centres, hawker centres, wet markets, public housing void decks, cemeteries, and even in secluded forested areas.

These shrines infuse sacrality into Singapore’s urban landscape, defying the neat binaries of what is regarded as sacred and secular, as well as legal and illegal in the city-state. Created and sustained by different communities, these public shrines are incredibly diverse. Their scale ranges from a modest altar set up at the foot of a banyan tree (regarded as sacred in several religions practised in the region) to more extensive standalone constructions with shelters. These shrines can serve a variety of deities, such as Sufi and Malay saints, South Asian gods and Taoist deities, but more interestingly, a single shrine may feature deities from multiple religions. Though marginal and easily overlooked due to their inconspicuous nature, these ‘hidden’ shrines reveal significant narratives that complement and extend those of larger, more established official places of worship.

Different Deities under One Roof

One of the most remarkable features of these wayside shrines is that many of them house deities from different religions under the same roof. A common deity worshipped at these shrines is Datuk Kong, who has Chinese and Malay origins. The deity is also known as Na Du Gong and Na Tuk Gong in Mandarin or Datuk Keramat in Malay. Datuk and kong means ‘grandfather’ in Malay and Mandarin respectively—a reflection of the guardian spirit’s Sino-Malay roots.

Worshipped in Singapore, Malaysia and Indonesia, Datuk Kong’s power of protection is limited to the area where he resides, and his shrines are typically small. Besides general safeguarding, devotees may also ask for lucky numbers to buy lottery tickets. A researcher of Datuk Kong shrines in Penang writes of the deity’s functions:

“[Datuk Kong] guard[s] worshippers against evil spirits and keep them from physical harm and injuries including traffic accidents, infestations by snakes and rats, termites, hornets, centipedes, scorpions, infliction of wounds from nails and broken glass and falling from trees and buildings and so forth. [Datuk Kong] safeguard[s] residents from natural disasters such as fire, lightning, floods, storms, landslides, epidemics and other catastrophes. In other words, Datuk Kongs safeguard life and property, and ensure the general well-being of the community.2”

Datuk Kong figurines can be identified by some form of Malay dress, most commonly the songkok or haji cap. This anthropomorphised representation of Datuk Kong is believed to have originated in Malaysia in the 1980s3. Other versions of the deity are dressed in a baju Panjang (long, loose-fitting tunic) and a sarong. He is usually depicted as seated, with legs apart, in a projection of authority. Despite his majestic aura, the deity wears a kindly demeanour and is said to exude a ‘grandfatherly’ presence with his beard, smile and portly belly. Occasionally, Datuk Kong is accompanied by a pet tiger.

Located in a carpark near Dickson Road in Little India is a collection of shrines, two of which worship Datuk Kong. They are placed on either side of a bamboo clump. The Taoist Tua Pek Kong, commonly known as the God of Prosperity, can also be found at one of the shrines, along with several Thai Buddha heads sitting atop a metal filing cabinet. The pink-coloured altar with its sculptures of Buddhist and Taoist deities were apparently donated by a grateful devotee who had won the lottery.

Other deities commonly found in wayside shrines are the Bodhisattva Avalokitesvara, or Guanyin, who represents compassion and mercy, worshipped by Buddhists and some Hindus; and the Hindu elephant-headed Ganesha, whom devotees pray to for help in eradicating obstacles in their lives. Both deities attract worshippers from different religious faiths.

The prevalence of these shrines reflects the multireligious social fabric of Singapore, made up of immigrants and transient workers who brought along their respective religious beliefs and gods. For instance, outside the well-known Thai enclave of Golden Mile Complex is a large Thai Buddhist shrine dedicated to the four-faced Phra Phrom, also known as the Hindu god Brahma. Phra Phrom has a popular following in Singapore and statues of the deity are found in various informal shrines across the main island as well as on Pulau Ubin.

Ephemerality

As these shrines are informal in nature and not officially recognised by the authorities, their existence becomes very precarious in fast-changing Singapore. Many of such shrines have disappeared over time — removed due to their illegal status or to make way for urban renewal.

In a few instances, they have been relocated by their caretakers if new homes could be found. Such wayside shrines are thus marked by a sense of ephemerality. This uncertainty creates an urgency to document these sites and their stories, including those of their communities, before they vanish from the landscape.

The vulnerability of these informal sacred spaces is highlighted in the 2010 destruction of the keramat (shrine) dedicated to the Sufi saint Siti Maryam (1830s–54). The term keramat can refer to several things, one of which is the sacred burial site of a Muslim saint. For decades, worshippers would visit the tomb of Siti Maryam in the Kallang area to pay their respects and seek her blessings. She was believed to be a miracle healer who could bring about clement weather, ensure employment and protect seafaring groups, including fishermen, sailors and coastal communities, by interceding with God on their behalf. Despite protests by the followers of Siti Maryam, her keramat was exhumed and demolished in April 2010 to make way for a new development. Such stories are not uncommon across different religious communities in Singapore.

More fortunate was a shrine along Niven Road that had been relocated multiple times between 2009 and 2020. Not only was it physically moved, its form, gods and identity also underwent transformation over the years. In 2016, it was located on the public pavement adjacent to a private property. Four years later, the shrine’s caretakers received a notice from a government agency ordering the shrine to be moved to a private space. As a compromise, the caretakers who worked nearby came up with an ingenious idea: they relocated the shrine, embedding it within a wall enclosing their private compound, with one side of the shrine jutting out just enough for the public to access it from the outside for worship.

In fact, the research team later discovered that the shrine was once located under a gigantic banyan tree on Niven Road. It is notable that over the span of a decade, through the three relocations of the shrine, its identity transformed from a tree shrine to a roadside shrine. Along the way, the pantheon of gods worshipped at the shrine also expanded: the original Taoist deities were subsequently joined by gods from other religions, including Hinduism and Buddhism.

Given the temporal nature of these wayside shrines, the Hidden Shrines database was developed to document their origins and history.

The Hidden Shrines Database

To be launched by the first quarter of 2023, the Hidden Shrines database is an online crowdsourcing initiative that documents small, informal but no less important shrines in Singapore. The digital humanities project was conceived by a team comprising members from Nanyang Technological University’s School of Computer Science and Engineering, and the School of Art, Design and Media. Computer scientist Dr Owen Noel Newton Fernando and a team of students led the development of the website.

Taking cues from the key characteristics of the shrines — primarily their intimate connection with their respective locations—the project fuses traditional art historical methods with a geographic information system, or GIS. The former includes fieldwork, photography and archival research, while the latter refers to the use of geospatial data as well as tools for recording, organising, analysing, manipulating and displaying that data.

Based on the shrines’ geospatial information, the website visualises their locations all over Singapore. The site features photographs of the shrines, either taken by the research team or contributed by the public. Besides providing a visual record of the shrines, the time stamps of the photographs become crucial research data as the shrines are highly vulnerable to destruction and relocation.

Additionally, the database includes information such as the date the shrines were established, the deities worshipped, patterns of patronage, ritual activities, architectural features and audio stories. This allows researchers and the public to study the shrines and discover narratives that may otherwise remain hidden.

The online platform aims to encourage physical encounters with the shrines. Users such as researchers, heritage enthusiasts and devotees can locate shrines using the website and then visit the actual sites. There, they may interact with caretakers, make offerings or participate in religious rituals on auspicious days. The database seeks to promote awareness of these small sacred spaces that have become invaluable repositories of tangible and intangible cultural heritage in Singapore. Apart from functioning as an archive, the website is also a means of sustaining the city’s hidden and less familiar cultural practices.

Caretakers and Devotees

Informal shrines are built and maintained by a communal network comprising caretakers and devotees, with many of the shrines sharing a common characteristic: the role of the elderly in their care and maintenance.4 King-Chung Siu and Thomas Kong, who conducted a study of such shrines in Hong Kong and Singapore, noted that “these shrines occupy the margins of the urban fabric, but serve unintended social and religious functions, primarily for the community of elders”.5

Mohamed Hassan, fondly known as Wak Ali Janggut6 (Bearded Ali) for his trademark long white beard, was the de facto custodian of Keramat Siti Maryam for a quarter of a century. Now in his 80s, Wak Ali used to live on the premises of the shrine, in a simple makeshift room with nothing more than a mattress and a small cupboard, and a mosquito net for protection.

Even though Wak Ali had a flat to live in, he preferred to live near the shrine so that he could care for it. While the shrine still existed, his daily chores included sweeping up dead leaves in the compound and replacing old flower offerings with fresh ones. He was known for his fervent prayers and used to worship with the devotees.7

Wak Ali was not just a caretaker who maintained the cleanliness of the sacred space; he was also a living repository of stories about the keramat and the unofficial custodian of its history. He shared his knowledge about the shrine’s secret spiritual passageway:

“The tree at the eastern end of the keramat contains a passageway that is the point of entry for spirits — this is the entry into the cave, [and the] cave is like a palace.8”

The narratives surrounding these shrines range from personal histories tied to the sites to supernatural incidents that may seem spurious and therefore incredulous to a nonbeliever. However, it is precisely such narratives that impart social significance to these sites. Regardless of their credibility, these anecdotes, which are transmitted firsthand or retold through other sources, give life and character to the shrines. Another caretaker of Keramat Siti Maryam, Wak Aiyim, had been visiting the shrine since he was a child. Recalling his supernatural encounters, he spoke of vision he once saw of Malay folk heroes:

“After I had finished work — I used to be a barber at a tree behind [the northeastern side of the] shrine — I fell asleep only to be woken up by a vision. I was shocked when I saw the faces of Hang Tuah, Hang Kasturi, Hang Jebat, Hang Lekir and Hang Lekiu on the five trunks of the tree. I then wrapped five pieces of yellow cloth9 around the trunks of a tree with five stems… Other spirits are at the shrine always to watch over people and reveal their powers whenever there is misconduct.10”

There are also female caretakers who help establish and maintain informal shrines in Singapore. For instance, Madam Quek was the informal caretaker of the Monkey God Tree Shrine that appeared in Jurong West Street 42 in 2007. The shrine was erected after some people observed an outline on a tree bark bearing resemblance to the Chinese monkey god Sun Wukong and the Hindu monkey god Hanuman.

The phenomenon drew large crowds of devotees who presented offerings and asked for blessings. Subsequently, calluses of two nearby trees were also ascribed sacred significance as representations of Guanyin and Ganesha. Although the initial enthusiasm shown by both Taoist and Hindu devotees faded, Madam Quek, who lives in the vicinity, continued to visit the shrines often, offering incense and tidying up the shrines. Sadly, these shrines have since been removed by the authorities for encroaching on state land.

Another female caretaker is Madam Veni, a priestess at the Sree Eranchery Bhagavathi Temple, which began as a family tree shrine in the 1940s devoted to the Hindu goddess Kali. Situated close to the former Keretapi Tanah Melayu railway tracks in Kranji, the shrine was located on a plot of state land that the family believed to be theirs. Over time, the shrine evolved into a larger temple with spaces to worship multiple Hindu gods and goddesses: Vishnu, Lakshmi, Mariamman, Ganesh, Shiva and Muneeswaran.

Madam Veni’s relationship with Kali goes back to her childhood days when the goddess revealed herself to her. She would occasionally go into a trance, during which Kali would communicate through her. For many years, Madam Veni conducted prayers and maintained the temple.11 In September 2020, the temple was demolished after the Singapore Land Authority delivered a notice for its removal.

Typically, many of such shines have self-appointed caretakers who preserve the sanctity of these places so that worshippers can continue to pray and pay their respects. Over time, communities also form organically around these sacred spaces. At some shrines, you may see devotees and caretakers socialising at times, sitting on plastic chairs and chatting.

Re-enchanting the Everyday

For sociologist Terence Heng, temporary roadside altars and shrines function as “‘transient aesthetic markers’ that reify the imaginary spiritual realm, allowing individuals to temporarily overlay spiritual and sacred space onto the physical and material space”.12 Indeed, wayside shrines produce and expand sacred space in response to the spatial constraints imposed by the state. Strict zoning laws, the prohibitive cost of land and high-density living make these informal shrines an appealing option for devotees.

Above all, the shrines are repositories of religious practices that are rooted in everyday life. Although much more modest compared to official religious establishments, these sacred spaces nonetheless represent aspects of ordinary lives, their individual and neighbourhood histories intersecting with national narratives. By paying closer attention to our surroundings, we may yet realise how much sacrality and religious heritage are infused into our everyday environments.

This article is adapted from ‘Hidden Shrines of Singapore’, a project supported by the National Heritage Board Research Grant.

The authors would like to thank Carol Wong, Faisal Husni, Vimal Kumar, Stefanie Tan Kai Ying, Alena Rae Ong, Goh Sheng En Darryl, Grace Amanda, Bryan Liu Jiaho, Chu Hao Pei, Isaac Ng, Goh Jun Le and Hien Van Tran for their contributions to the project.

Notes

- Vineeta Sinha, ‘Marking spaces as “Sacred”: Infusing Singapore’s Urban Landscape with Sacrality’, International Sociology, vol. 31, iss. 4 (2016): 469 – 70.

- Cheu Hock Tong, ‘The Datuk Kong Spirit Cult Movement in Penang: Being and Belonging in Multi-Ethnic Malaysia’, Journal of Southeast Asian Studies, vol. 23, iss. 2 (September 1997): 383.

- Cheu, “The Datuk Kong Spirit Cult Movement in Penang, September 1997”, 388.

- King-Chung Siu and Thomas Kong, ‘Informal Religious Shrines: Curating Community Assets in Hong Kong and Singapore’, The International Journal of the Inclusive Museum, vol. 6, iss. 2 (2014): 90.

- Siu and Kong, 2014, 90.

- Wak is a Malay term used to refer to an older man, while janggut is Malay for ‘beard’.

- Nurul Huda Rashid, ‘Siti Maryam Shrine, Keramat Siti Maryam, Kallang’, 2014. Retrieved from https://www.facebook.com/241771483120592/posts/makam-kallang-tok-ali-dankembar-buaya-post-credit-sutaribin-supari/507508606546877/.

- After the demolition of the shrine in 2010, NUS Museum curated an exhibition to remember the holy site that once was. Teren Sevea, ‘Listening to Leaves: Historical Memory of a Keramat in Contemporary Singapore’, in The Sufi and the Bearded Man: Re-membering a Keramat in Contemporary Singapore (Singapore: NUS Museum, 2011), 15.

- It is Malay custom to wrap yellow fabric around a sacred site, including on trees deemed to have spiritual significance.

- Sevea, 2011, 13.

- Interview with Madam Veni, 4 September 2020. 12 Terence Heng, ‘An Appropriation of Ashes: Transient Aesthetic Markers and Spiritual Place-making as Performances of Alternative Ethnic Identities’, The Sociological Review, vol. 63, iss. 1 (2015): 57–78.