Text by Wong Xinyuan, Loh Yi Fong/Nanyang Technological University

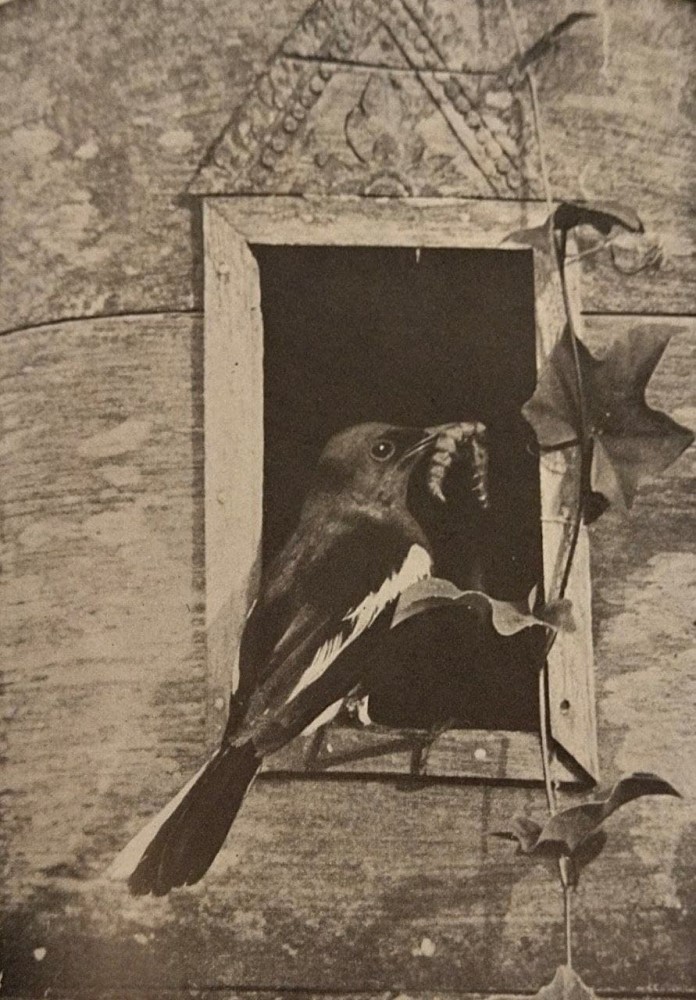

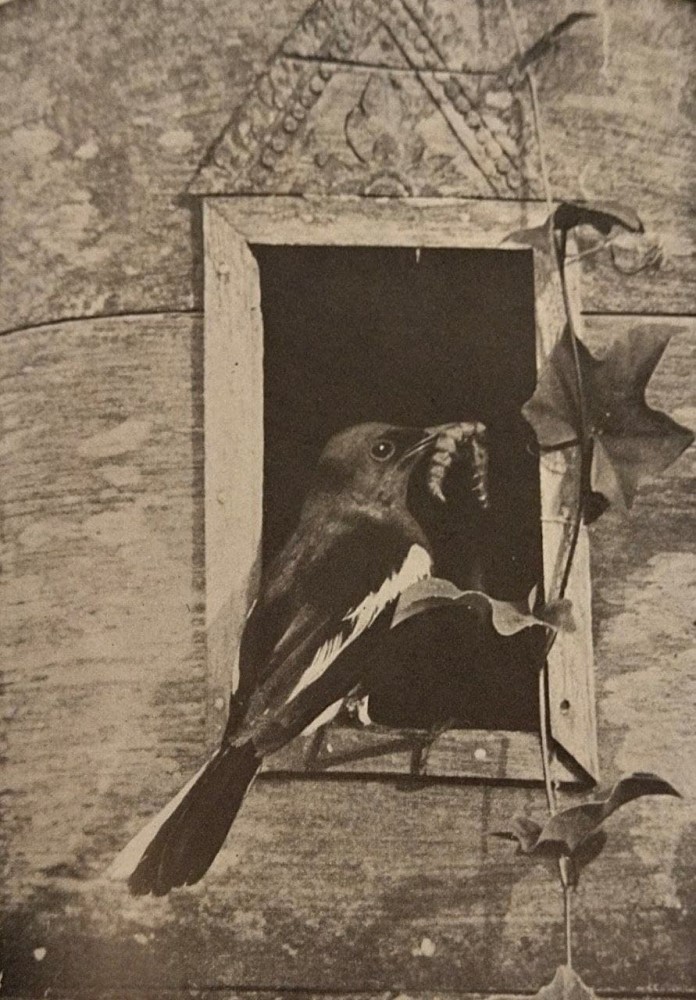

A bird chirps in its captivity in a Sembawang homeowner's flat. Years ago,

this area used to be mangroves, ponds, mudflats, and grasslands. An early

dawn’s bird-watch could yield fifty distinct species in the early 1970s.

Might birds in the wilderness that used to exist there, have chirped similarly

- and who remembers their birdsong till today?

Senoko (Sungei Sembawang) map 1990, p.97, from the Master Plan for the

Conservation of Nature in Singapore, by Malayan Nature Society (Singapore

Branch), ISBN 981-00-2327-8.

Senoko (Sungei Sembawang) map 1990, p.97, from the Master Plan for the

Conservation of Nature in Singapore, by Malayan Nature Society (Singapore

Branch), ISBN 981-00-2327-8.

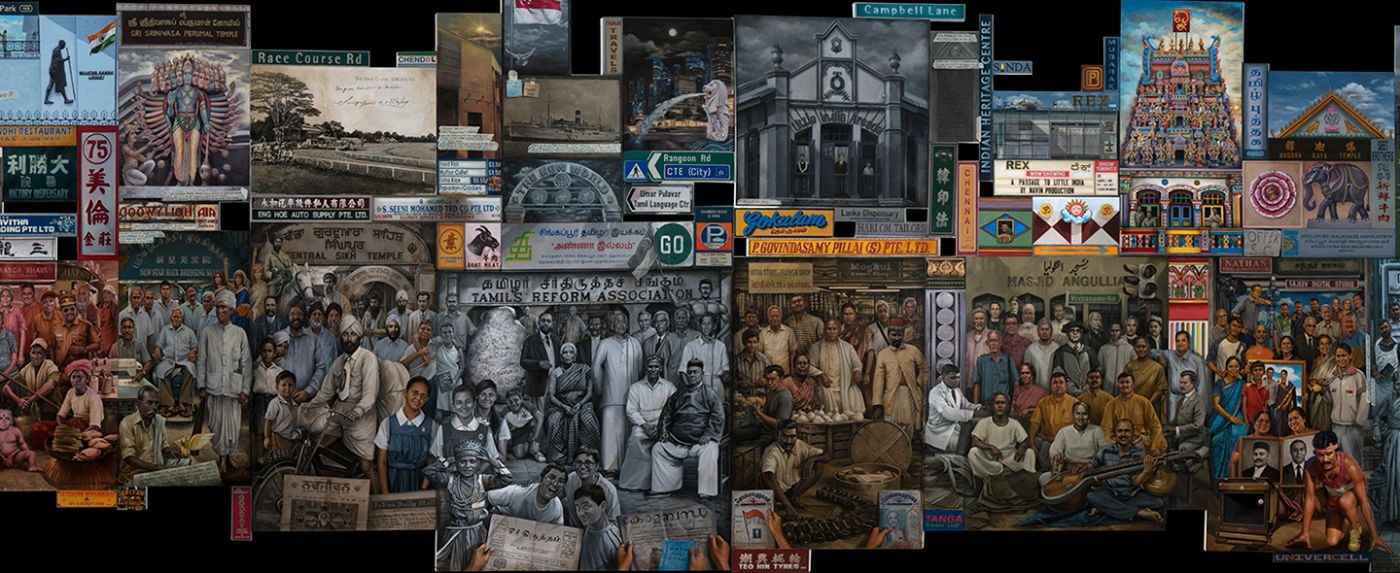

Birds are a part of our natural heritage. Firstly, it is not only Nature

Society (Singapore) (NSS) Bird Group, the Kebun Bahru Birdsinging Club, or

specialists who know bird species by name. Many older Singaporeans still have

latent knowledge about birds, harkening back to their childhoods in kampongs.

Secondly, Singapore is a biodiversity hotspot where birds play key roles in

the ecosystem, helping to maintain them, while also connecting us to the past.

The Oriental Magpie Robin (Copsychus saularis) is a curious native species,

once so common as to be known as the “Straits Robin” by British

naturalists in the then Malayan Nature Society. The birdwatching community

renamed the bird to Magpie Robin after realising that it was also found

elsewhere beyond the Straits Settlement. ¹ Among common folk, its names

included the Murai-Kampung Biasa, 鹊鸲, and kuruvi. In the process of

exchanging names, communities congregated to admire its magnificent birdsong.

²

Image of an oriental magpie-robin, originally from Natural History Museum,

Tring, United Kingdom. 1856, Specimen collected by A. R. Wallace in Bali

(Copsychus amoensis),

♂

. Credits to Yuchen Ang. Retrieved from

https://wallace.biodiversity.online/species/A-Vert-Aves-000081

Image of an oriental magpie-robin, originally from Natural History Museum,

Tring, United Kingdom. 1856, Specimen collected by A. R. Wallace in Bali

(Copsychus amoensis),

♂

. Credits to Yuchen Ang. Retrieved from

https://wallace.biodiversity.online/species/A-Vert-Aves-000081

Magpie approaching nest. 1956, photograph also from Guy Madoc, from

‘An introduction to Malayan birds’.

Magpie approaching nest. 1956, photograph also from Guy Madoc, from

‘An introduction to Malayan birds’.

Besides the local’s immersion in nature, birdwatching trips became an

important way to pay more attention to the natural world. As our interviewee,

Tan Gim Cheong from NSS Bird Group, shares, present-day bird enthusiasts

follow a well-trodden path in learning the ways of the birds around us. As the

hobby of going on nature walks spreads to more ordinary people, curiosity and

interest in making kin with the non-human leads them to eventually study

naturalists’ books and know the times of the year when a bird is

nesting, that dawn is the best time to go bird-watching, and eventually all

their names, just like how youngsters get acquainted with the game

“Pokemon”.

Jarvis, from Birds of Singapore 2018, Birds of Singapore, Retrieved from

https://www.amazon.sg/Birds-Singapore-Christopher-Hails/dp/9814794473

Jarvis, from Birds of Singapore 2018, Birds of Singapore, Retrieved from

https://www.amazon.sg/Birds-Singapore-Christopher-Hails/dp/9814794473

A Naturalist's Guide to the Birds of Singapore. 2013, Retrieved from

https://singapore.kinokuniya.com/bw/9781912081653

.

A Naturalist's Guide to the Birds of Singapore. 2013, Retrieved from

https://singapore.kinokuniya.com/bw/9781912081653

.

Tan Gim Cheong is a 49-year-old Singaporean man who heads the Bird Group of

NSS. Not only did he discuss how technology and the passage of time have

influenced birding practices, he also shared about the role played by museums,

naturalists, and illustrators in cultivating an appreciation of birdlife. NSS

is one of the oldest and most reputable environmental organisations in

Singapore, having split off in 1991 from its predecessors - the Malayan Nature

Society (1940) and Singapore Natural History Society (1921). While digital

photography tends to be taken for granted today, illustrations and drawings

were an important way of getting to know the birds of Malaya, and remain

important in emphasising characteristic features.

1970s was a time of rapid urbanisation. The Animals and Birds Act was passed

in 1965 to regulate the bird trade. Bird trade was more strictly regulated

with vaccinations and checks on diseases, as well as rigorous import-export

limits. Many imported or traded pet birds that were not native to Singapore,

such as parrots and macaws. This meant increased complexity in how

biodiversity was managed. Imported birds that escape could potentially become

invasive, harming native birds and disrupting local ecosystems.

The magpie robin declined from being common in earlier days, to requiring a

re-introduction programme by NParks in the early 1980s. Gim Cheong comments

that this was initially assessed to be a failure, as the re-introduced birds

may have been poached, however the magpie robin is now a regular at some

sites.³ Today, it remains a threatened species, and in many places has

been replaced by the Javan mynah.⁴ ⁵

Male Magpie Robin on park ground. 11 August 2019, National Parks.

https://www.facebook.com/nparksbuzz/photos/the-native-oriental-magpie-robin-is-a-nationally-threatened-species-and-was-form/2504266332946161/

Male Magpie Robin on park ground. 11 August 2019, National Parks.

https://www.facebook.com/nparksbuzz/photos/the-native-oriental-magpie-robin-is-a-nationally-threatened-species-and-was-form/2504266332946161/

Today, kampongs are replaced by high-rise buildings that we associate with the

Housing Development Board (HDB), while birdsong appreciation has shifted from

wild birds to caged imported birds. Citizen science programmes aim to build

understanding and love for biodiversity among Singaporeans, as does the

calendar provided by LepakInSg provide a means of joining different

environmental activities. ⁶ The annual Bird Race by NSS Bird Group continues

to gather competing teams to count as many birds as possible at dawn. Many of

these birds remain common in natural heritage areas, like

Pulau Ubin

and Sungei Buloh Nature Reserve.⁷

Will the cry of the magpie robin still be known and loved by children today

who grow up in the urban landscape and not wilderness? Will our streets become

silent?

About Partner

Wong Xinyuan is an undergraduate of Nanyang Technological University

majoring in history. She is interested in transforming the relationship

between nature and humans. She is keen to understand how the effects of

climate change and socioeconomic disparity intersect to form developmental

challenges for Southeast Asian societies.

Loh Yi Fong is an undergraduate of Nanyang Technological University minoring

in history and science, technology & society. He is an incoming graduate

student in the History of Science, Technology and Medicine at the University

of Minnesota-Twin Cities in Fall 2022. He was inspired by his dad’s

love of birds whilst growing up in Changi.

This article was developed for Singapore Heritage Fest 2022