Text by Szan Tan

Be Muse Volume 7 Issue 1 – Jan to Mar 2014

In the course of preparing for the 2014 exhibition ‘A Changed World: Singapore Art 1950s-1970s’ one of the challenges that confronted my co-curator, Daniel Tham, and myself was the use of terms in discussions about modern art in Singapore. These terms in themselves demarcate boundaries which limit and exclude – and, in many instances, these boundaries are extremely ill-defined. The result is a problematic set of terms which one may, at best, use loosely, and with the utmost care due to their inadequacies. In particular, the contention over the use of the terms ‘pioneer’ and ‘second generation’ is one which we would like to explore further1. This article makes no attempt to resolve the issues of categorisation; rather, it aims to encourage readers to reflect on these terms, and to appreciate the richness and complexities of our art history.

Of The Term ‘Pioneer’: Inclusions and Exclusions

The term ‘pioneer artists’ is commonly used in writings on local art history. So who are these recognised ‘pioneers’ of our visual art history? Who are those who are consistently regarded as ‘pioneers’? Are there geographical and age limits that are attached to the term? From when do we chart the beginnings of our visual art history?

According to the Merriam-Webster dictionary, the term ‘pioneer’ refers to ‘a person or group that originates or helps open up a new line of thought or activity or a new method or technical development’, or ‘one of the first to settle in a territory’. If we were to combine both definitions, then the term ‘pioneer’ would refer only to immigrant artists, resulting in the loss of an important facet of our culturally diverse history as important non-immigrant artists would be excluded from this category. Geography and chronology further complicate matters, for the study of Singapore’s history and its art cannot be divorced from the history of Malaya, which, in turn, brings us back to the colonial period. And if we say our visual history has its roots in the colonial period, how early should we start tracking it, and on what grounds?

From the late 1980s to early 1990s, ‘pioneer’ status has been conferred on artists like Liu Kang, Cheong Soo Pieng, Chen Chong Swee, Chen Wen Hsi, Lim Hak Tai, Georgette Chen and Lim Cheng Hoe, with the latter three occasionally forgotten and omitted. All seven artists were Chinese immigrants who had settled in Singapore before and after World War II, trained and tutored a great number of art students, and later became full-time artists. The conferment of ‘pioneer’ status carries with it the understanding that these artists significantly impacted and contributed to the local art scene. While there is no doubt these seven artists deserved it, many more artists should be remembered as pioneers as well.

Artist Tsang Ju Chi, for example, is a forgotten pioneer. Trained in Shanghai and Paris, Tsang arrived in Singapore in the 1930s and actively organised art exhibitions featuring works depicting local subject matter. Although he was chiefly involved in commercial art, he was dedicated to promoting local art, especially in his capacity as the chairman of the Society of Chinese Artists. He also sought to groom young artists by organising the Youth Encouragement Society art exhibitions2. As a painter himself, he was known for his oil paintings of local Malay folk and fishermen. Unfortunately, none of Tsang’s works survived. He was killed in the Sook Ching massacre during the Japanese Occupation.

Besides Tsang, artists such as Suri Mohyani, M. Sawoot bin Haji Rahman and Mahat bin Chaadang, Lee Ta Pai, Liu Sien Teh, Chong Pai Mu, See Hiang To, Chen Jen Hao, Wu Tsai Yen, Fan Chang Tien, Chang Tan-Nung and Sunyee should be regarded as pioneer artists for their significant contributions as artists and art educators in our history. When examining our art history, it is also important to note the significance of Penang. Hence, the works of the pioneers who were active there - in particular, Abdullah Ariff and Yong Mun Sen - should be taken into account too when studying Singapore’s early art history. And if we were to rethink the constraints of time and space in our history, should we not regard the dedicated art inspector and artist Richard Walker - who made great contributions to the development of watercolour painting in Singapore and Malaya - as a ‘pioneer’ too?

‘Second Generation’: When Does It Begin?

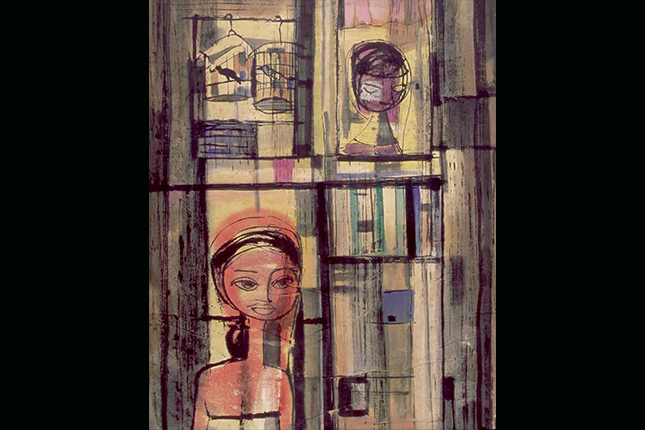

The term ‘second generation’ probably began to appear in the late 1990s to early 2000s. It generally referred to artists who were most probably taught by ‘pioneer’ or ‘first generation’ artists. In many cases, it is assumed that the artists received training at the Nanyang Academy of Fine Arts, or that they were taught by the ‘pioneers’ privately, or in classes held at Chinese medium schools. It is also believed that many of these ‘second generation’ artists received further training in art overseas, particularly in the United Kingdom, other European countries and the United States. Artists who went to these countries to study in the mid-1950s to the early 1970s, such as Thomas Yeo, Yeo Hoe Koon, Anthony Poon, Teo Eng Seng, Ng Eng Teng, Tan Teo Kwang, Wee Beng Chong and Goh Beng Kwan are generally categorised as ‘second generation’ artists. Choy Wen Yang, Lu Kuo Siang, Latiff Mohidin, and Eng Tow are also categorised as second generation artists due to their overseas training, but they were not taught by any first generation artists.

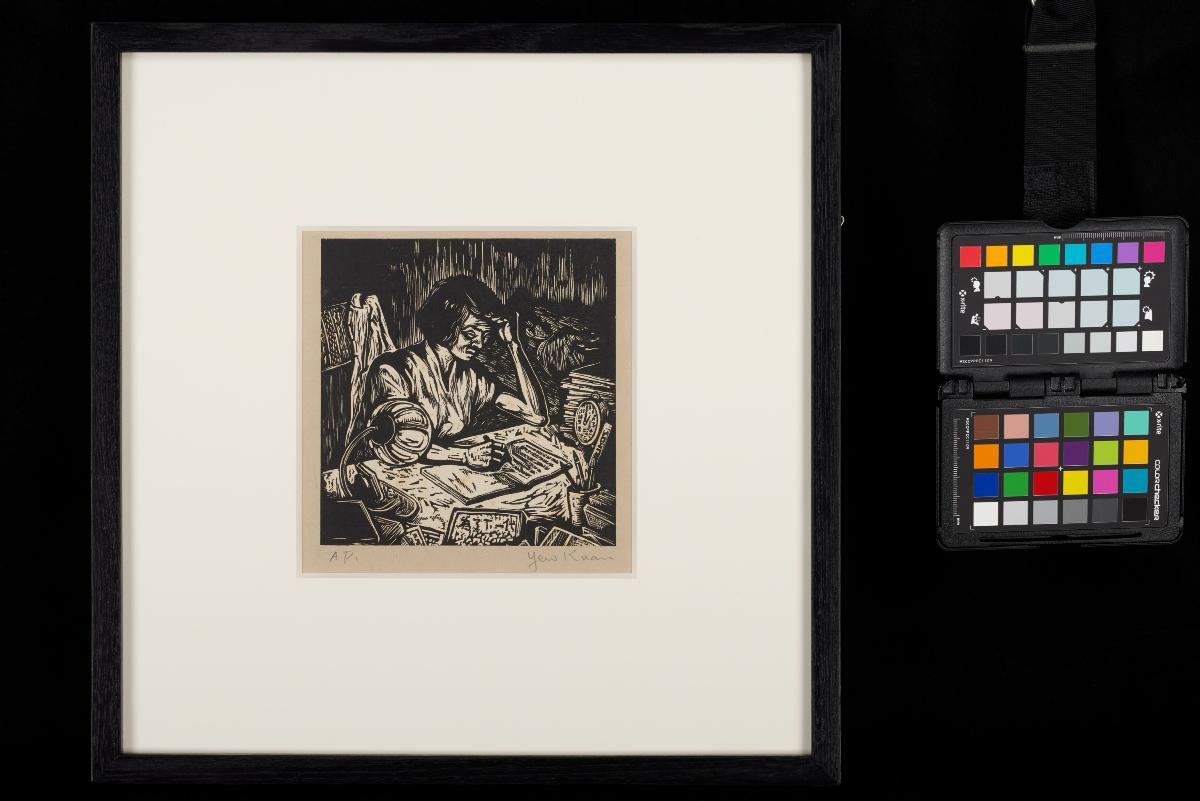

And then, there are the artists who did not have the opportunity to be trained overseas in Western countries - students of the ‘first generation pioneers’, who were successful in their own right. These include artists such as Tay Chee Toh, Tan Ping Chiang, See Cheen Tee, Foo Chee San and Koeh Sia Yong. Moreover, the term ‘second generation’ also implies that these artists stood for and embraced Western abstraction in their art3. For example, Tay Chee Toh is widely recognised as a ‘second generation’ artist. However, the boundaries start to blur again in the case of artists who were students of the first generation who did not embrace Western abstraction. These artists include Ong Kim Seng, a prominent watercolour artist; See Cheen Tee and Foo Chee San, who specialised in wood block printing; as well as Koeh Sia Yong and Chua Mia Tee, who adhered to realism throughout their careers.

Then there is the issue of time: when does the ‘second generation’ begin? Should the limits of a generation be defined, or should one only consider the peak of an artist’s career as the period of time that defines his or her generation? Can artists such as Lai Foong Moi, Foo Chee San, Choo Keng Kwang, Lim Tze Peng, Chua Mia Tee, Chen Cheng Mei and Yeh Chi Wei and Abdul Ghani Hamid – all of whom were born between 1910s and 1930s – be regarded as ‘second generation’? How should we categorise these artists, who do not fit the mould of ‘pioneers’ or ‘second generation’ artists? Or should we simply ignore these categorisations and honour these artists for their unique contributions to our art history?

Indeed, the use of the terms ‘pioneer’ and ‘second generation’ throws up more questions than answers, raising issues that will not be immediately – or ever – resolved. This is because the reality of art-making and its history is not one of neat and convenient categorisations. The spirit of a milieu can be ingrained in an artist’s works but if he/she is to be called an ‘artist’ in the first place, his or her unique voice has to come through and withstand the test of time - and transcend boundaries.

Szan Tan is Curator, National Museum of Singapore

The contentions surrounding the use of the term and category ‘first generation pioneers’ and ‘second generation’ were first raised in 2007 by Wang Zineng in his endnotes to the article ‘Curatorial Notes’, in the exhibition catalogue ‘Bodies and Relationships: Selected works of Lee Sik Khoon’, presented by NUS Museums.

2 Hsu, Marco (translated by Lai Chee Kein), A brief history of Malayan Art, Millennium Books, Singapore, 1999.

3 The abstract works of these artists should not be seen merely as imitations or derivations of Nicholson, Rothko, Motherwell, De Kooning, Pollock, Kline or Hoffman for their expressions possess a universality that transcends space and time. At times an Eastern spirit can be detected in the use of strokes, lines, and composition.