TL;DR

A close examination of four historical neighbourhoods in the city centre reveals multi-ethnic demographics that defy Singapore’s official racial classification.

MUSE SG January 2023

Text by Dr Imran bin Tajudeen, Senior Lecturer, Department of Malay Studies and Department of Communications and New Media, National University of Singapore

Read the full MUSE SG January 2023

It is commonly assumed that the ethnic compositions of the historic conservation areas of Chinatown, Kampong Glam, Little India and Emerald Hill conform to Singapore’s official classification of ‘races’ — ‘Chinese, Malay, Indian and ‘Others’. But looking back at history, we now know that, in reality, these neighbourhoods were multi-ethnic in character. Similarly, there were other neighbourhoods whose compositions also defied this commonly used framing, one that ignores many erstwhile places and communities that thrived in colonial Singapore.

Kampong Melaka, Kampong Bengkulu, Kampong Serani and Kampong Dhoby were four such neighbourhoods that used to be located in the city centre, but few traces of them remain today. Here we unearth stories of the social fabric and built environment of these old kampongs.

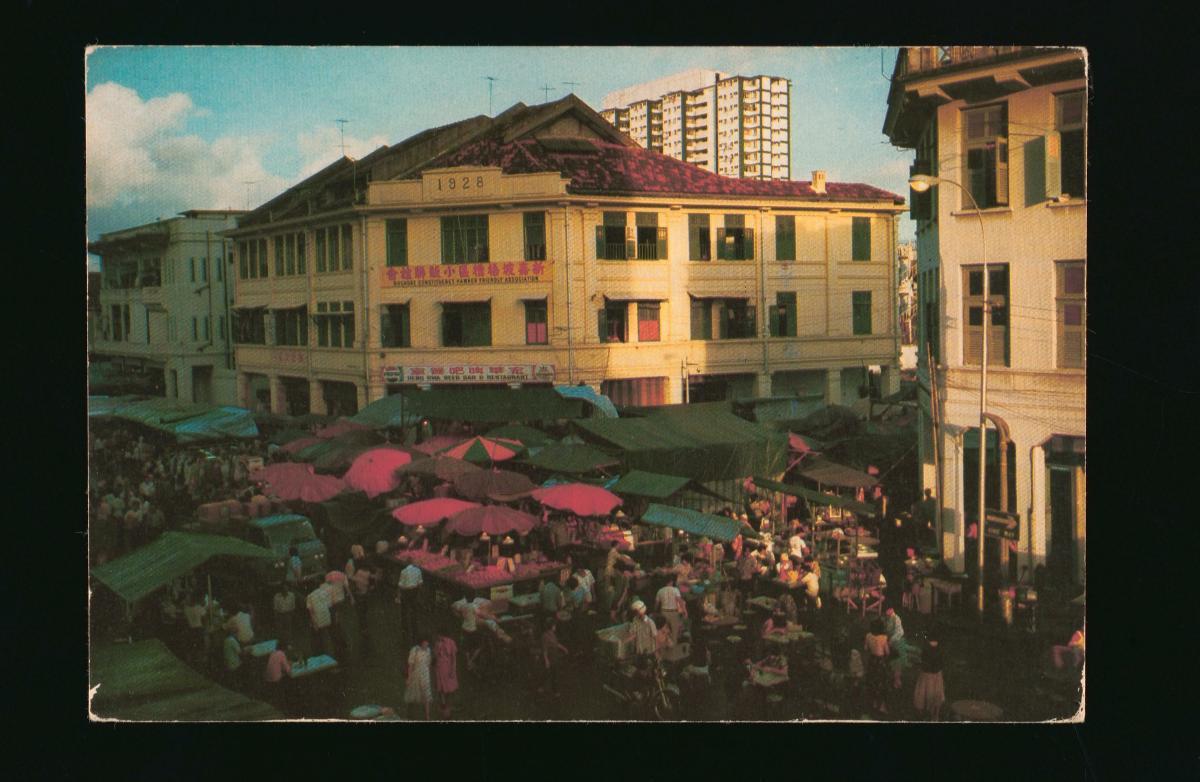

Kampong Melaka

The former Kampong Melaka comprised northern and southern sections separated by the Singapore River. North Kampong Melaka was located in what is now the historic district of Clarke Quay, while South Kampong Melaka encompassed today’s Angus, Cumming, Fisher, Kerr, Keng Cheow and Solomon streets, near the Clarke Quay train station. However, the original Kampong Melaka was in fact situated further downstream, at the northern bank of the Singapore River where the Parliament House currently stands.

With the East India Company’s establishment of a trading settlement in Singapore in 1819, the Melakans, whom the British Resident and Commandant Major William Farquhar had encouraged to relocate to Singapore, settled upriver from Kampong Temenggong (roughly the site of today’s Asian Civilisations Museum). They formed the first Melakan settlement in Singapore, which was mentioned in an autobiographical account of the early years of Singapore after the British arrival, the Hikayat Abdullah (1849). But besides the Melakans and the Temenggong settlement, the Chinese — mainly Teochews — also lived among them.

However, Raffles had other plans for the northern bank of the river: he wanted to reserve it for official or civic uses. In June 1819, he issued instructions for all the Chinese and Malays to move to the southern bank of the river. The Chinese would form the enclave known as ‘Chinese Town’, stretching from the mouth of the river to Presentment Bridge (also known as Jackson Bridge; later replaced by Elgin Bridge), and a ‘Malay Town’ for the Malay community that would be sited upstream of the bridge.

However, Raffles’s instructions for a Malay Town to be set up just inland from the Chinese Town was subsequently amended in two ways. First, his second set of instructions resulted in the area just slightly upriver being designated as ‘Chulia Campong’ in the 1822 plan of Singapore town, popularly known as the Jackson Plan. Second, what in fact formed organically on the site was a settlement called Kampong Melaka, comprising a mixed community of Malays and Jawi Peranakans from Melaka, as well as Teochews and other groups.

Kampong Melaka’s composition demonstrates a common theme in Singapore’s colonial history: areas demarcated for specific ‘races’ or ethnic groups quickly morphed into diverse, mixed neighbourhoods even as early as the first two decades of British arrival in Singapore.

A Multiethnic Settlement

Kampong Melaka was home to a diverse, multiethnic community. Many of its residents came from Melaka and comprised Malays, Chinese and Jawi Peranakans. The latter group included the author of the Hikayat Abdullah, Abdullah bin Abdul Kadir, better known as Munshi Abdullah. A resident of Kampong Melaka in the 1840s, Abdullah was hired by Raffles as his Tamil-Arab Malay language teacher and clerk.1

The Jawi Peranakans, who were Muslims of Indian and Malay extraction, were particularly prominent as property owners in the area. They included Hajee Saiboo (who owned a shophouse within the grounds of Omar Mosque), Hadjee Mahamad Arip2 (four shophouses on Omar Road), Mona Kadei Mydin3 (four shophouses on Keng Cheow Street) and Sultan Meydin (a shed on Wayang Street). Arab, Bugis, Malay and Chinese families also owned properties in the vicinity of Omar Mosque, attesting to the heterogenous character of the kampong.

The Chinese in Kampong Melaka

Kampong Melaka was an important neighbourhood for the Chinese community, particularly the Teochews. The concentration of prominent Teochews in this area was largely due to Temenggong Abdul Rahman’s efforts to cultivate plantations in pre-colonial Singapore. The Teochews, Bugis and Malays had been operating gambier plantations across Singapore at the behest of the Temenggong, the island’s Malay chief and de facto ruler before British colonial rule. At least 20 plantations existed in the immediate vicinity of the town when Raffles arrived in Singapore.4 Several mansions owned by eminent Teochew merchants were sited along the river and nearby at Hill Street and High Street, including that of Seah Eu Chin,5 who along with other family members were highly influential merchants. Near the Teochew market in Kampong Melaka was Chin Hin Street, named after Seah’s business in 1870.6

Places of Worship

Being a predominantly Muslim settlement, Kampong Melaka’s focal point was Masjid Omar Kampong Melaka (Omar Kampong Melaka Mosque) built in 1820, originally a simple wooden structure with an attap roof. Originally located off Mosque Square, accessed from Omar Road (both expunged) off Havelock Road, the mosque compound featured several rumah limas (hip-roof houses) and two rows of shophouses. Masjid Omar Kampong Melaka bears the name of its benefactor: Pangeran Syarif Syed Omar bin Ali Aljunied, one of Singapore’s pioneers and a Hadhrami Arab who arrived here from Palembang in southeastern Sumatra. His son Syed Abdullah rebuilt the mosque in brick in 1855, which later underwent several major reconstructions.

As there was also a significant Chinese population residing in the neighbourhood, in 1826 the Teochews established their main temple, Wak Hai Cheng Bio, close to the south bank of the Singapore River opposite the former Kampong Temenggong. Five decades later in 1876, Tan Seng Haw/Po Chek Kio7 was built on Magazine Road as the assembly hall and temple of the Tan family from Melaka. The temple was noted for its role in mitigating disputes and providing protection for newly arrived Chinese immigrants. In 1885, the temple was rebuilt and named Tan Si Chong Su, which was gazetted as a national monument in 1974.

Chinese Wayang Houses and Opium Shops in Kampong Melaka

Six Chinese theatre halls were known to exist in Kampong Melaka, three of which were located along the now-expunged Wayang Street. Wayang is the Malay and Javanese term for ‘theatre’, which, interestingly, has become part of the vocabulary for describing traditional Chinese opera. Heng Wai Sun (Qing Wei Xin; 庆维新) and Heng Seng Peng (Qing Sheng Ping; 庆升平) were two theatre halls on Wayang Street.8 Both were venues for Cantonese opera, but the latter also hosted Beijing and Hokkien operas.9

In addition to theatre halls, two opium shops were constructed in 1910 at 14 Merchant Road and 44 Merchant Road, operated by members of the Seah clan, Seah Liang Seah and Seah Eng Kiat respectively. Another opium shop opened two years later at 71 New Market Road, run by one Tan Jui Eng.

Kampong Bengkulu

Kampong Bengkulu (Bencoolen) encompassed the properties at present-day Albert Street, Prinsep Street, Bencoolen Street, Short Street, Middle Road and Waterloo Street. This was where a group of Malays from Bencoolen (Bengkulu in Indonesia today), whom Raffles had brought to Singapore, made their home.

Newspaper notices from early as 1844 indicate that addresses at Queen Street and Church Street (later renamed Waterloo Street) were usually accompanied by the words ‘Campong Bencoolen’. For instance, a forum letter contributor to the local newspaper in 1846 wrote “Queen Street, Campong Bencoolen” and signed off as “A Resident in Church Street, Campong Bencoolen”.

Interestingly, although the area was designated as the ‘European Town’, this label was never used by the locals, who instead named the area according to how they perceived it. In Hokkien, Albert Street was known as Kam Kong Mang Ku Lu (Kampong Bengkulu), ‘Mang Ku Lu’ being the transliteration of ‘Bengkulu’.

Diverse Places of Worship

At the centre of Kampong Bengkulu was a mosque of the same name, built in 1845. Like the mosque in Kampong Melaka, Masjid Kampong Bengkulu was a recipient of Syed Omar bin Ali Aljunied’s wakaf (a permanent endowment for charity). Pre-dating the mosque, however, were two churches: the Catholic Chapel (1833) and the Malay Chapel (1843; also known as Greja Keasberry10), which in 1885 became the Prinsep Street Presbyterian Church. The existence of these early churches in Kampong Bengkulu can be traced to its earlier demarcation as the European quarter before the kampong took shape. Records indicate that by the mid-19th century, Malays and other groups were present in the area alongside Europeans and Eurasians as both residents and building owners.

In 19th-century Singapore, the colourful, multiethnic composition of the area was apparent with the diversity of its religious landmarks. The latter half of the century saw the establishment of St Joseph’s Church (1853) on Victoria Street by the Portuguese Mission; Bethesda Chapel (1866) on Bras Basah Road; Sri Krishnan Temple (1870), Maghain Aboth Synagogue (1878) and Kwan Im Thong Temple (1884) on Waterloo Street; Our Lady of Lourdes Church (1886) on Queen Street catering to Tamils from Pondicherry, India; and the Tamil Methodist Church on Short Street (1887).

Forgotten Lorongs

A unique feature of Kampong Bengkulu was its relatively large building plots. These were originally intended for the substantial mansions or compound houses used by the European community. While some of these plots were used for large houses, others were subdivided for the building of shophouses. Because the shophouses occupied only a third of the large plot sizes, property developers created alleys or lanes (lorong in Malay) to access the interior of the plots and built microtenements there. The only surviving example of such a land division in the area is Prinsep Place, formerly known as Cheang Jim Chuan (Chwan) Place.

The developers of four lorongs in Kampong Bengkulu have been identified as Hadjee Mohamed Bin Abdul Rahim (Lorong Sakai), Hussensah Marican (Lorong Serai), Haji Kader (Lorong Sepang) and S. Kassim (Lorong Kassim). It is significant that these four personalities were either Malay or Indian; Haji Kader and S. Kassim were Tamil Muslim merchants from Bombay who were part of the Jawi Peranakan community.

Indeed, there was an exceptionally large number of Arabs and Tamil Muslims who owned properties or lived in Kampong Bengkulu. A search of land records from the 1840s shows that more than half of the total number of plots at lower Prinsep Street, lower Bencoolen Street and lower Waterloo Street, as well as the northwestern corner of Bras Basah and North Bridge roads, were owned by Arabs or Indian Muslims.

Kampong Serani

Within Kampong Bengkulu was Kampong Serani in the vicinity of Queen Street and Manila Street. ‘Serani’ is the Malay equivalent of the Arabic ‘Nasrani’ (Nazarene), which refers to Christians. Among Malay speakers of the past, Portuguese Eurasians, who were typically Catholic, were known as Serani.

Kampong Serani, which was bounded by Hokkien, Manila and Queen streets, was called Sek-kia-ni Koi (Serani Street; a transliteration of ‘Serani’) in Hokkien.11 Kampong Serani was known for its Eurasian community, the offspring of intermarriages between local women and early European settlers.

Burgeoning Catholic and Christian Populations

A Eurasian neighbourhood was clustered around the Portuguese Mission, which later built St Joseph’s Church in 1953. Prior to this, members of the Portuguese Mission community used to gather at the house of Jose d’Almeida, a Portuguese surgeon who came to Singapore to start a dispensary and subsequently became a successful merchant. D’Almeida’s residence was a mansion along the seafront Beach Road before the coastline was pushed out by reclamation.

Although predominantly Catholic and Christian, the resident makeup of Kampong Serani was far from homogeneous. Besides the community of Catholic Eurasians, there were many other groups affiliated to various Catholic missions and Christian denominations, whose churches and communities were embedded in the area. These communities were in fact multiethnic and multilingual.

Initially, most Catholics worshipped at Singapore’s only Catholic chapel on Bras Basah Road, built in 1833 at the site that was later occupied by St Joseph’s Institution, and today the Singapore Art Museum. As the congregation grew, however, another larger place of worship was completed in 1847 — the Church of the Good Shepherd located at the corner of Bras Basah Road and Queen Street. Subsequently, more churches in the surrounding area sprang up catering to specific ethnic groups and Christian denominations as the various communities expanded.

The first Catholic community to establish its own church was the Portuguese Mission, who built the original St Joseph’s Church in 1853 on Victoria Street (the building we see today is a newer construction dating to 1912). Chinese- and Tamil-speaking Catholics were served by the Church of Saints Peter and Paul on Queen Street that was built in 1870. As the Tamil congregation expanded, however, they moved to the Church of Our Lady of Lourdes on nearby Ophir Road, founded by the French mission from Pondicherry in 1888. A short distance away at Short Street, the Tamil Methodist Church was built here in 1887, signalling the burgeoning Methodist community in the area.

Meanwhile, the Baba Malay-speaking Chinese Peranakan community from Melaka formed the Straits Chinese Church, also referred to as the Malay Chapel, in 1843. This later became Prinsep Street Presbyterian Church, which was also known as the Prinsep Street Baba Church. Besides locally born Straits Chinese, the Chinese Peranakan community from Bencoolen and some Teochew speaking Christians also joined this congregation. Another Baba Malay-speaking church, Straits Chinese Methodist Church, at the intersection of Middle Road and Waterloo Street was inaugurated in 1894.

Compound Shophouses

Many Eurasians lived in compound shophouses — a dwelling formed by setting back a row of shophouses or terrace townhouses and enclosing the front yard with a low brick wall, thus creating a small front compound. The houses were also raised from the ground with a short flight of steps leading from the front yard to the terrace. At one point, there were 15 rows of such compound shophouses in the vicinity of Kampong Serani.

Zena Tessensohn née Clarke recalled living in a bungalow on a lane opposite the Church of Saints Peter and Paul:

“Many Eurasian families lived in Queen Street… We used to visit each other’s compounds or gardens and play hide-and-seek and catching. The boys used to fly kites and play marbles… [The] younger members mixed and played together a great deal, especially as the open compound of the older row of houses allowed for participation by large numbers in games such as hantu galah, rounders, etc.”

However, this architectural typology did not extend to the newer style of shophouses, as Marie Cockburn née de Souza remembered:

“The newer second row of shophouses had no common compound. Rather, each house had an enclosed concrete area leading from a gate to the front verandah of the house. This area could be used for parking a car or for lining potted plants.”

As the Eurasian community flourished in Kampong Serani, so did institutions and businesses owned by Eurasians that supported their social and economic lives. There was a Eurasian-run pineapple factory on Bencoolen Street as well as an Italian bakery and the Mercantile Institution on Queen Street, the latter founded by P.E. Pereira, who also served as its principal. One of the compound houses on the same street was converted into the Mercantile Hostel.

Kampong Dhoby

Within the vicinity of Kampong Bengkulu, near Kampong Serani was Kampong Dhoby (also spelt ‘Dobie’ and ‘Dobi’) at the upper end of Queen Street. This was a neighbourhood inhabited by a North Indian community. In Tamil, this area was known as Dobi Kampam, kampam being a transliteration of the Malay ‘kampong’. Maps from 1842 – 45 indicate that Kampong Dhoby had existed by then, while a newspaper notice from 19 May 1842 mentions a “Campong Dhoby”.12

Kampong Dhoby owes its origins to the location of the Indian military cantonment here in the 1820s as well as the section of the Rochor River where Indian washermen, or dhobies, washed and dried their laundry. The soldiers at the cantonment were recruited from Bengal and brought to Singapore to maintain law and order. The cantonment in the vicinity of Short Street existed for about six years before it shifted to Outram Road. It was described as a “large exercising ground… roughly bounded by Prinsep St., Albert St., Queen St., and Bras Basah”.13 However, even after the relocation of the cantonment, the Indian presence remained, leading to the formation of Kampong Dhoby.

In 1906, Masjid Kampong Bengkulu became known as Masjid Hanafi, following a change in the mosque’s trusteeship to Hanafi adherents of the Muslim faith. Just two years later, another Hanafi mosque was established in 1908 — Queen Street Hanafi Mosque, which was commonly known as Masjid Benggali. These developments attest to the shifting demographics of Kampong Bengkulu and its growing number of Indian Muslims, many of whom subscribed to the Hanafi school.

Besides the two mosques, the kampong was also home to one of the earliest Sikh temples in Singapore, the predecessor of today’s Central Sikh Temple on Towner Road. This Sikh temple (gurdwara) was first set up in 1912 in a house at 175 Queen Street, which had been acquired by a group of Sikhs led by a Sindhi merchant named Wassiamull. The gurdwara represented the Sikh community’s early attempt at self-organisation, and the site soon became a centre for Sikh social life. The confluence of activities at the temple earned it the name Wadda Gurdwara, or Big Temple. In 1920–21, the building was converted into the Central Sikh Temple, and remained here until 1977 when the land it sat on was acquired by the government.

Another major landmark in this area was the first office and printing press of the Utusan Melayu newspaper, which published its maiden issue in 1939. The pioneer Malay-language press occupied a three-storey shophouse on Queen Street. However, the premises were destroyed during the Japanese Occupation, and the press subsequently reopened on Cecil Street.

This article is adapted from ‘A Fine-grain History of Singapore Town: The Architecture and Sociomorphology of Four Forgotten Neighbourhoods’, a research project supported by the National Heritage Board Research Grant.

Notes

- Skinner, ‘Shaer Kampong Gelam Terbakar oleh Abdulllah b Abdul-Kadir’. Journal of the Malaysian Branch of the Royal Asiatic Society, vol. 45, iss. 1 (1972): 26–27.

- ‘Mahamad’ may be spelt as ‘Muhamad’ or ‘Mamad’.

- ‘Kadei’ may be spelt as ‘Kader’.

- W. Bartley, ‘The Population of Singapore in 1819’. Journal of the Straits Branch of the Royal Asiatic Society, vol. 11, iss. 2 (1993): 177.

- Song Ong Siang, One Hundred Years’ History of the Chinese in Singapore (Singapore: National Library Board, Singapore: World Scientific, 2020 [1923]) 62, n.55.

- Ng Yew Peng, What’s in the Name? How the Streets and Villages in Singapore Got Their Names (Singapore: World Scientific, 2018).

- The temple was known by many different names including Bo Chiak Kung, Po Chek Kiong, Po Chiak Keng and Bao Chi Gong.

- Paul van der Veer, Da Xi: Chinese Street Opera in Singapore (Netherlands: The Author, 2008), 22.

- F.H. Lew, ‘Park Road School. Part 8’. Singapore Memory Project, 2017.

- Greja is Malay for ‘church’. It was called the ‘Malay Chapel’ because of its Baba Malay-speaking congregation. The chapel was also known as Greja Keasberry, named after its founder Reverend B.P. Keasberry of the London Missionary Society.

- H.T. Haughton , ’Native Names of Streets in Singapore’. Journal of the Straits Branch of the Royal Asiatic Society, vol. 23 (1891): 51, 58.

- [Untitled], The Singapore Free Press and Mercantile Advertiser, 19 May 1842, 3.

- Murfett et al, 2011, 57.