TL;DR

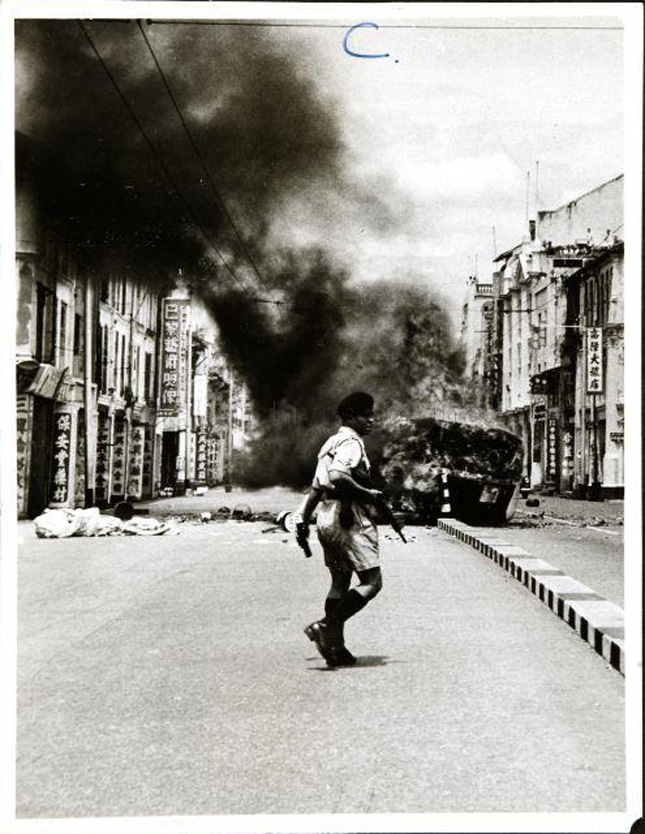

The year was 1956. The authorities, having started clamping down more heavily on leftist activities, were deregistering subversive organisations such as the Singapore Chinese Middle Schools Students’ Union1 and arresting agitators.2

These measures drew the ire of thousands of Chinese middle school students who, started sit-ins which later erupted into protests on the streets of Singapore. The violent clashes, in what became known as the Chinese Middle School Riots, took the lives of 13 and injured 123.3

Notes

1 https://eresources.nlb.gov.sg/history/events/376486b7-a68b-4a2b-acad-97e0b678a8e7#2

2 https://eresources.nlb.gov.sg/history/events/376486b7-a68b-4a2b-acad-97e0b678a8e7

3 https://www.straitstimes.com/opinion/revisiting-operation-coldstore

4 https://www.washingtonpost.com/news/volokh-conspiracy/wp/2017/11/07/lessons-from-a-century-of-communism/

5 https://www.straitstimes.com/asia/east-asia/timeline-of-chinas-cultural-revolution

6 https://eresources.nlb.gov.sg/infopedia/articles/SIP_1563_2009-09-30.html

7 https://www.straitstimes.com/singapore/why-we-must-not-forget

8 https://eresources.nlb.gov.sg/history/events/376486b7-a68b-4a2b-acad-97e0b678a8e7

9 https://eresources.nlb.gov.sg/infopedia/articles/SIP_822_2004-12-28.html

10 Southeast Asia and the Cold War. Edited by Albert Lau, p. 54

11 https://eresources.nlb.gov.sg/history/events/376486b7-a68b-4a2b-acad-97e0b678a8e7

12 https://eresources.nlb.gov.sg/history/events/376486b7-a68b-4a2b-acad-97e0b678a8e7

13 https://eresources.nlb.gov.sg/history/events/376486b7-a68b-4a2b-acad-97e0b678a8e7

14 https://eresources.nlb.gov.sg/history/events/376486b7-a68b-4a2b-acad-97e0b678a8e7

15 https://eresources.nlb.gov.sg/history/events/376486b7-a68b-4a2b-acad-97e0b678a8e7

16 Southeast Asia and the Cold War. Edited by Albert Lau, p. 54

17 Southeast Asia and the Cold War. Edited by Albert Lau, p. 54

18 Southeast Asia and the Cold War. Edited by Albert Lau, p. 54

19 Southeast Asia and the Cold War. Edited by Albert Lau, p. 54

20 https://eresources.nlb.gov.sg/history/events/376486b7-a68b-4a2b-acad-97e0b678a8e7

21 https://eresources.nlb.gov.sg/history/events/376486b7-a68b-4a2b-acad-97e0b678a8e7

22 https://www.mindef.gov.sg/oms/imindef/mindef_websites/topics/nexus/what_we_have/connexionsg/2016/SGPeople/6reasonswhydevannairisyolo.html