Text by Goh Seng Chuan Joshua

MuseSG Volume 11 Issue 1 - 2018

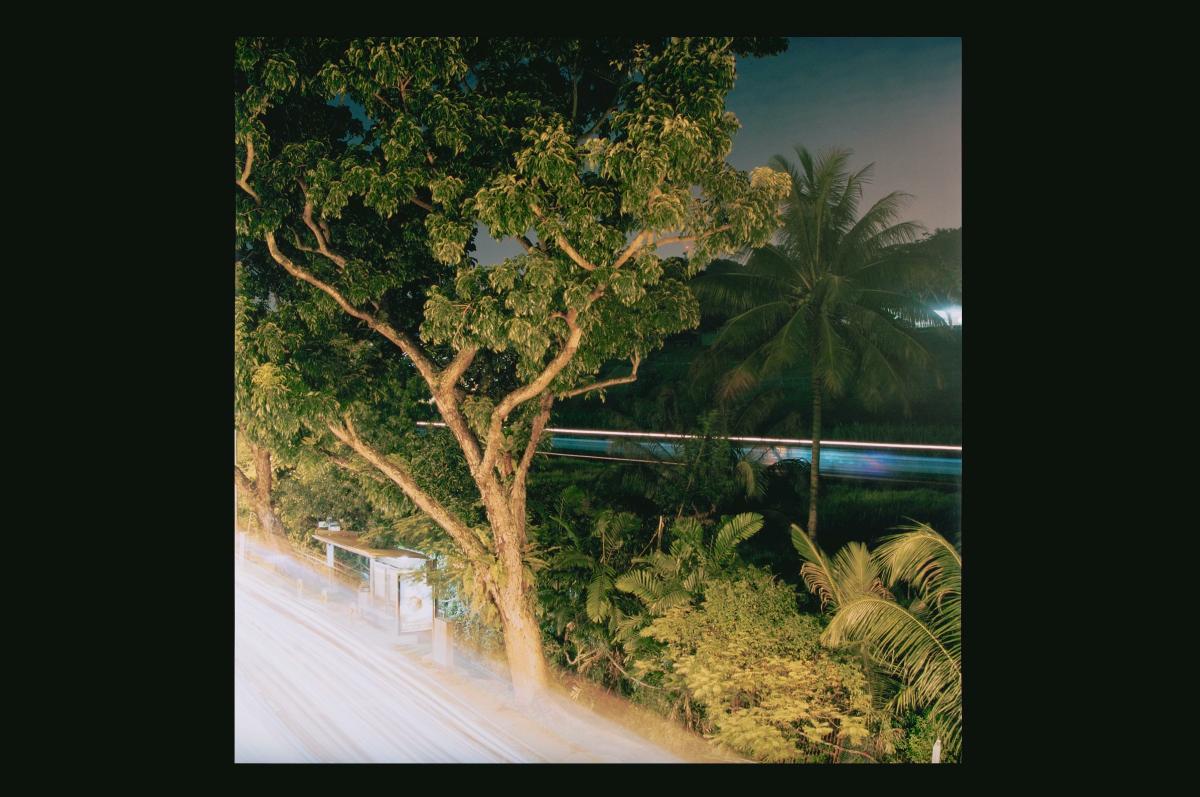

Mention Bukit Panjang to any Singaporean and images of a typical Housing & Development Board (HDB) town will likely come to mind. In fact, a peak-hour trip through Bukit Panjang on a Light Rapid Transit (LRT) train will bring one face-to-face with rows of towering residential flats, punctuated occasionally by the odd park or community space. As the train-car glides into Bukit Panjang Integrated Transport Hub, waves of passengers can be glimpsed hurrying along, some bound for the spanking new Hillion Mall. A quick glance, and it is soon apparent that many of these commuters have just arrived via the adjacent Downtown Mass Rapid Transit (MRT) Line, returning for a day's work in the city.

Half a century ago, however, the commute to Bukit Panjang would have had been made not in air-conditioned comfort, but in a Vulcan omnibus operated by the Green Bus Company.

Trundling down Upper Bukit Timah Road on bus service No. 2, one would have encountered acres of dense foliage, interspersed with factories belching out thick, grey smoke. Every now and then, a cacophony of intoned hawker voices would have wafted through the bus’ opened windows, as if attempting to compete with the periodic whistle of the Malayan Railway locomotive as it thundered towards the level crossing at Choa Chu Kang Road. As the bus wound around the traffic circus situated where Junction 10 stands today, a mishmash of zinc and brick shophouses would have come into view.

Known colloquially as chap kor (“tenth mile” in Hokkien), this was Bukit Panjang, a cluster of villages that comprised a few thousand residents during the 1950s.1

What histories were inscribed in the landscape of this seemingly nondescript town; or was it just another town on the byway?

Long before the advent of shopping malls such as Junction 10, “tenth mile” had already been used colloquially to refer to Bukit Panjang. In fact, the origins of both toponyms can be traced to the mid-1800s, when a number of settlements emerged at the 10th milestone of Bukit Timah Road, near a 132-metre hill known as Bukit Panjang (which means “long hill” in Malay).2 Initially inhabited by gambier and pepper planters, these settlements began to expand when Bukit Timah Road was extended northwards to Kranji in 1845. In the process, new forms of economic activity such as rubber cultivation were introduced to Bukit Panjang.3 In 1912, the well-known business magnate Ong Sam Leong was reported to have tapped the first tree at his new Bukit Panjang Rubber Estate, which was located at the 101⁄2 milestone of Bukit Timah Road. That such estates were likely a defining feature of the then Bukit Panjang landscape is also suggested by a Malaya Tribune report of 1916 announcing the auction of another possibly similar rubber and coconut estate at Chua Chu Kang Road near the Bukit Panjang Railway Station.

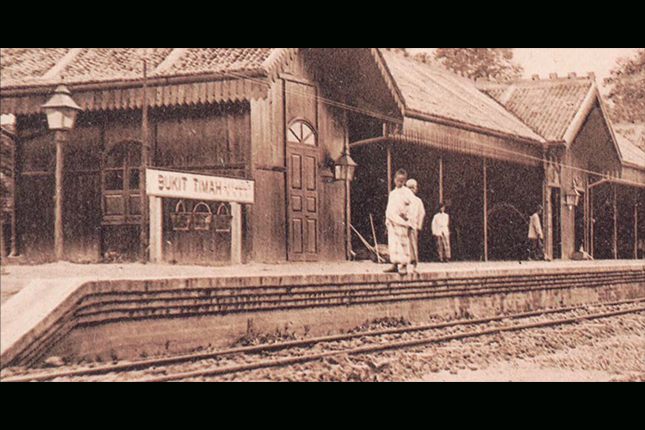

Situated near today’s Bukit Panjang Post Office, the now defunct Bukit Panjang Railway Station was also integral to the town’s rapid growth in the early 1900s. Constructed as part of the Singapore Railway in 1903, it was by 1912 incorporated into the Federated Malay States Railway. This meant that it would have been possible to proceed by train from Bukit Panjang to Holland Road, Cluny Road or even Kuala Lumpur. According to a notice published in the Singapore Free Press and Mercantile Advertiser in 1910, trains were scheduled to call at Bukit Panjang station up to five times daily, carrying not only passengers, but also goods, mail, and even stone from the Mandai Quarry. In fact, an early description of Bukit Panjang as a rather unremarkable locale is provided by a Straits Times reporter covering the opening of the railway line in 1903The engine whistled shrilly and in a few minutes drew up at Bukit Panjang, a small station not quite complete yet, of the Cluny Road type. Here, some Tamil women were noticed carrying baskets of gravel on their heads, the gravel being spread about the floor of the station. A few Chinese coolies came on board here and the train was soon speeding on its way.

As the town continued to evolve in the decades after, it is likely that the earlier image of Bukit Panjang as just another nondescript town became more an anachronism than a true reflection of its identity. Certainly, residents of Bukit Panjang in the 1950s would have been familiar with an altogether different town than the one described in the Straits Times report of 1903. The Bukit Panjang they would have known, far from being mundane, was brimming with verve and assertiveness, for it was a town which doggedly coupled a can-do ethos with a spirit of mutual help as it confronted the challenges of Singapore’s early nation-building years. No doubt it was roiled, at times, by the turbulent socio-political currents of the era, but this itself ensured that residents of Bukit Panjang forged a distinct collective identity defined by a strong sense of esprit de corps. Testament to the fact that this spirit of camaraderie was no myth, but was indeed being tangibly expressed, is a speech by the then acting Colonial Secretary J. D. Higham to the newly- formed Bukit Panjang Youth Club in 1954. Praising the club’s community centeredness, he pronounced with more than a sliver of prescience, that in Bukit Panjang “there is already a sense of belonging to a group”, from which he predicted would “grow [the] most fruitful movements”.

Part of the reason why a spirit of collegial solidarity began to take root so strongly in Bukit Panjang was the fact that the trunk road which brought development to the town was also the same feature that separated it by ten miles from the city. Indeed, a Singapore Free Press report of 1955 could not resist describing Bukit Panjang as the “vegetable basket” of Singapore – a “far off rural constituency of bullock-cart trails, away from the hurly-burly of city life”. Given this description, one can perhaps understand why residents of Bukit Panjang often came together to fend for themselves, especially in instances when help seemed distant, delayed or deficient. In 1957, for example, the Singapore Improvement Trust launched Bukit Panjang Estate (later renamed Teck Whye Estate), which comprised some 200 single-storey terrace houses.

Branded as a low-cost alternative for workers employed in the Bukit Timah area, the houses were touted in the local press as being “excellent shield[s] against heat and cold”, with their construction even bearing the approval stamp of a United Nations expert. Yet, by 1958, tenants were being told tartly by the trust’s chairman, J. M. Fraser, that they had to “help themselves” when they appealed for assistance to fix asbestos roofs that were producing oven-like indoor temperatures of 38 degrees celsius. In a Straits Times article from 1958, Fraser was even reported to have told tenants that the trust was “charging you a favourable rent which isn’t even economical for us”. Furious tenants, miffed that their petitions had been ignored, were reported to have organised a meeting at the Bukit Panjang Community Centre to decide on a course of action.4 Perhaps not coincidentally, within two weeks of the meeting, the matter was raised for discussion in the then Legislative Assembly.5

At times, the collective indignation felt by residents and workers of Bukit Panjang towards social injustice was so intense that meetings gave way to strikes, and petitions came to be substituted with the picket. Situated where Tan Chong Industrial Park is standing today, the Nanyang Shoe Factory – where many womenfolk from Bukit Panjang were reputed to have worked – was one compound beset by numerous strikes in the 1950s and 1960s. Although the charged political atmosphere of the day no doubt influenced strikers’ demands, newspaper reports from the era also reveal that on most occasions the strikers’ grievances stemmed from prosaic bread-and-butter concerns: the desire for a 50-cent wage raise or for overtime allowance to be granted. Industrial action undertaken was thus not necessarily always the handiwork of disruptive elements, but could well have been prompted by workers uniting to seek redress for injustices such as the refusal of a company to pay arrears. Chua Beng Tee, who witnessed many such strikes, recalls that “in the past, people took action once they felt aggrieved, no matter if it was a minor issue. That’s much less likely to happen today!”6

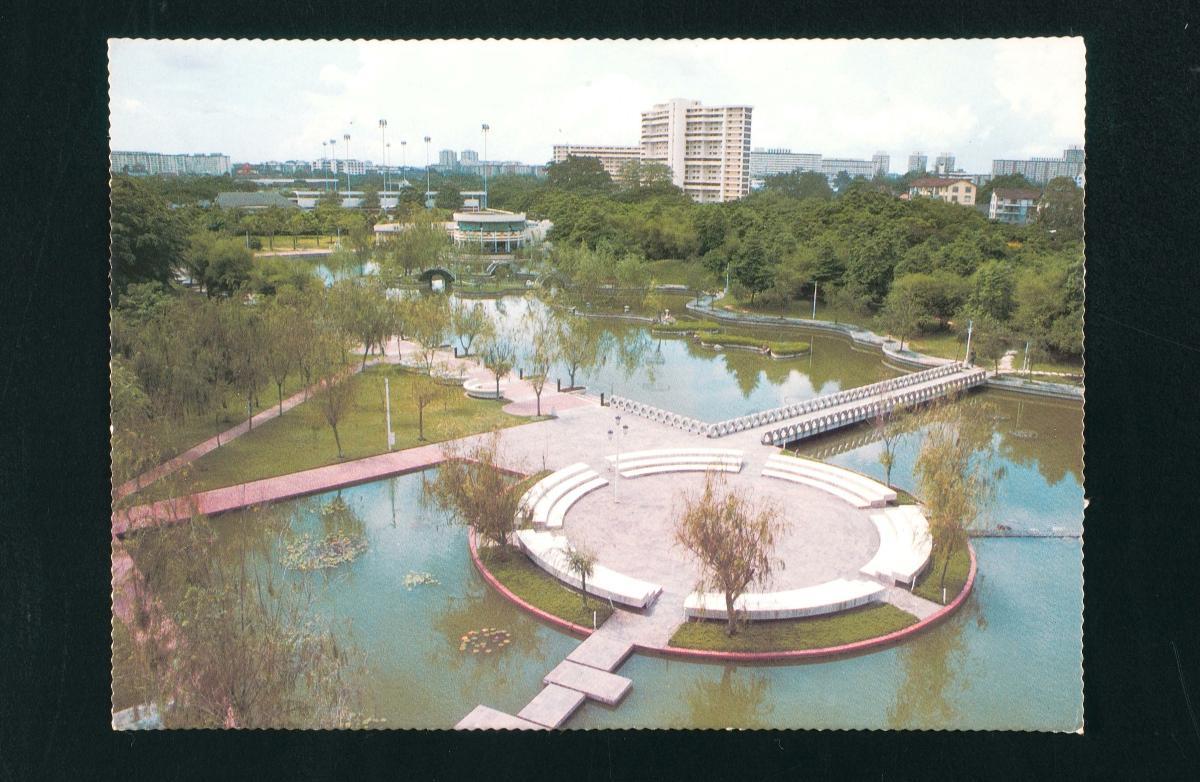

While a lively sense of disaffection certainly permeated through the Bukit Panjang of the 1950s and 1960s, more often than not the response it prompted amongst residents was a spirited attempt to channel this restiveness for a greater good. Bukit Panjang Community Centre, in particular, stood out for its many initiatives that attempted to tackle issues of both local and national dimensions. In 1955, the centre organised Singapore’s inaugural district horti-agricultural show, which included demonstrations for farmers, displays of crops, and even advice for carp breeders. At the show’s opening, then Chief Minister David Marshall publicly commended Bukit Panjang Community Centre for their public spirit in organising such an event, which he opined was “of great assistance”.

Not to be outdone, the community centre further down at Jalan Kong Kuan was also reported to have organised its fair share of charitable activities, on occasion using the Sin Wah Theatre near Lorong Ah Thia to screen shows as part of its fund-raising programmes.

Beyond the walls of such community institutions, it would be remiss to disregard the many instances in which this sense of public-spiritedness found expression through ground-up grassroots initiatives, pursued by ordinary Bukit Panjang residents of all races and creeds. A particularly revealing case involves the former Lembaga Masjid Jamik, which in 1960 began a building fund drive to build a mosque in Bukit Panjang, as the next nearest mosque was some seven miles away. Not content with merely raising funds, more than 100 volunteers from Bukit Panjang came together as part of a self-styled “Operation Masjid”, helping to clear the site on which the mosque would be constructed. The mosque, originally named Jamek Mosque, was subsequently renamed Al-Khair in 1963, and continues to serve the Muslim community at 1 Teck Whye Crescent today.

Over at Bukit Panjang Government High School, which was established as Bukit Panjang Secondary School in 1957, students who had barely turned 13 banded together when they arrived at their new school premises in Jalan Teck Whye in 1959 to find that there were no desks and chairs.7 Professor Low Cheng Hock, who was amongst the school’s first batch of students, recalls how all the students rushed to help carry the school furniture from a lorry when it arrived two weeks later. As weeks passed, the entire cohort even transformed the barren land behind the school into a proper field by planting grass seeds and nurturing it with cow dung.8

Peh Ching Boon, who attended the school in the 1960s, also discovered how valuable the close-knit ties amongst Bukit Panjang residents could be when on one occasion, a handful of students mischievously released the air valve of his bicycle’s tyres. Fortunately, he was spared a trek home by virtue of his uncle’s friendship with the school’s doctor, who brought him to a nearby shop to repair the leak. Moreover, he was even told he could henceforth park his bicycle outside the Principal’s office!9

Fast forward to today, the Bukit Panjang of the mid-20th century is scarcely recognisable amidst the rows of towering HDB flats. Nonetheless, a spirit of camaraderie continues to flourish amidst the high-rise urbanscape, testifying to the esprit de corps so strongly embedded in the town’s heritage.

For example, even as new initiatives such as community gardens have emerged, longstanding community institutions such as the Bukit Panjang Youth Club continue to flourish too, with the latter even pioneering signature programmes such as FoodNotes, a youth-led food donation drive for the needy.

Emblematic of the extent to which Bukit Panjang has managed to carve out a distinct identity is perhaps the sheer fact that its place-name continues to be used widely amongst Singaporeans, in lieu of the less familiar “Zhenghua”. In fact, “Zhenghua” had been chosen to replace “Bukit Panjang” as part of a government initiative in the 1980s to rechristen towns with “pinyinised” toponyms, but the original place-name was reinstated after a spirited public debate (Bukit Panjang was the only town in Singapore in which a reversal of the policy was effected).10 On hindsight, one can surmise from the episode that Singaporeans are, without a doubt, cognisant of the importance of place identities and histories, and how these work in concert to distinguish places like Bukit Panjang from being mere towns on the byway. In the words of geographers Brenda Yeoh and Lily Kong, it is only logical that:

Place and history are closely intertwined in the rich texture of individual and social life. There is no history without place, and no place without history; to lose sight of one would be to lose a sense of the other.11

Notes