Text by Maria Khoo Joseph

Be Muse Volume 7 Issue 3 - Jul to Sep 2014

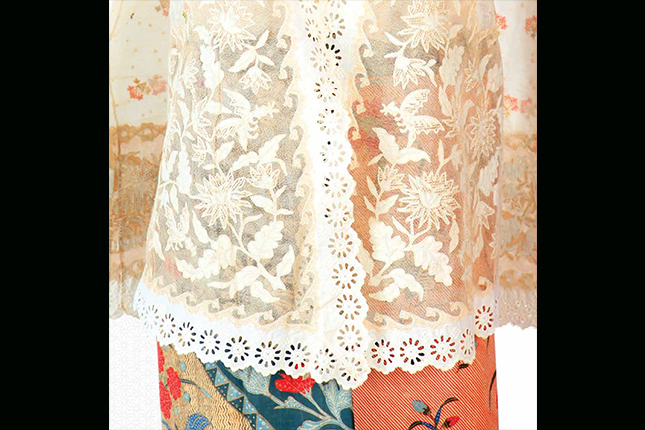

For many Peranakan Chinese of Southeast Asia, religion and ritual play a central role in their daily lives. Many ceremonies, from Chinese New Year to the annual tomb cleaning (cheng beng) festival, involve setting up altars and invoking deities and ancestors. Altars usually hold religious paraphernalia and offerings. On special occasions, textiles are draped in front.

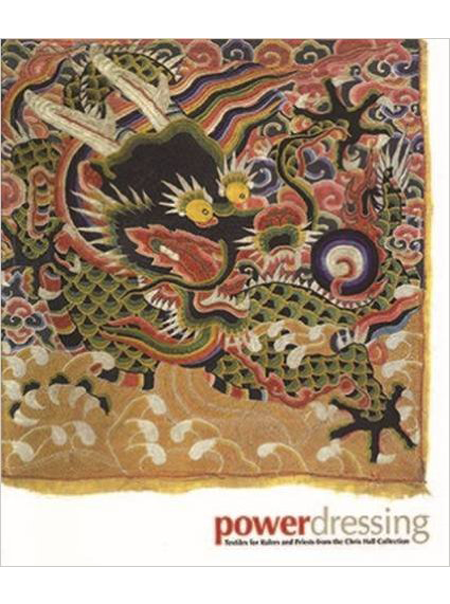

Altar cloths, called tok wi in Hokkien (zhuowei in Mandarin), are usually made of silk with embroidered designs and were originally imported from Southern China. Common motifs included dragons, phoenix, qilin, ruyi sceptre, swastika, and other auspicious symbols. The cloths are almost uniformly rectangular – to cover the shape of the front of a typical altar. An extra piece of fabric, also decorated, hangs as a flap over the upper section. Fragments of such hangings and altar frontals have been discovered in excavations of Tang-dynasty (618–907) monasteries near the Dunhuang Caves, in present day Gansu province, demonstrating that the tradition has been long-held.

Java, mid-20th century Cotton (drawn batik)

Gift of Matthew and Alice Yapp

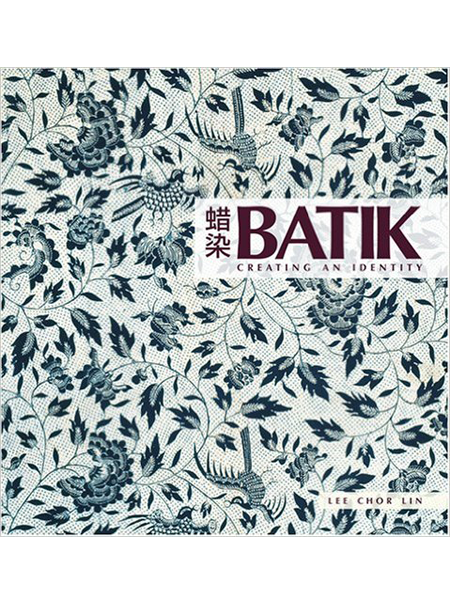

By the early twentieth century, Peranakans on Java began using altar cloths made of local batik. These batik altar cloths maintained the form of the embroidered versions, though they adapted established Chinese symbols in imaginative renderings and introduced motifs and designs from Southeast Asian and European cultures. Most batik altar cloths are designed on a single piece of cotton cloth, with depicted, rather than actual, upper panels. It is unclear why Peranakans of Java began using batik altar cloths, but perhaps it was due in part to the already thriving batik industry on the island. Another theory could be that the tropical climate of the East Indies was more suited to textiles made of cotton than of silk. Batik altar cloths show the distinct cross-cultural identity of the Peranakan communities of the region. They are fascinating examples of a community’s adaptation to its new surroundings.

China, early 20th century

Embroidered damask silk, cotton liner and tassels

THE EXHIBITION

The Peranakan Museum received a donation of seventy-two batik altar cloths from Matthew and Alice Yapp in 2012. The cloths were collected by their son Alvin over a period of ten years. On 11 April 2014, the museum opened the exhibition Auspicious Designs: Batik for Peranakan Altars, which featured several highlights from the collection. The exhibition was divided into five sections over two floors of the museum's special exhibition gallery.

The first section was a contextual display featuring a deity altar and a set of furnishings that might be found in a typical Peranakan home. An altar cloth was draped over the front of the altar table, embroidered hangings adorn the doorways, and chairs flanking the altar were also covered in embroideries. This display emphasised the importance of textiles in demarcating sacred space during special occasions.

The second section focused on the embroidered silk altar cloths made in China. These cloths were imported into Southeast Asia and used by Peranakans. An example on display was a full gold thread altar cloth depicting the Three Star Gods that once belonged to the Chee family, one of the oldest families from Malacca. This section showed examples of cloths that were forerunners to the batik versions produced later in Java.

China, early or mid-20th century

Silk with gold embroidery

The third and fourth sections of the exhibition examined the stylistic diversity found in the designs on batik altar cloths. Batik cloths in these two sections are decorated with designs that mix Chinese, Southeast Asian, and European influences.

One of the cloths prominently displayed the coat of arms of the Dutch East Indies at the centre, with Chinese cloud collar motifs at the sides. A selection of Chinese objects, from what are known as the Hundred Antiques, decorated the upper panel. This cloth is possibly one of the oldest batik altar cloths in the museum's collection: it was made using natural dyes.

Java, early 20th century

Cotton (drawn batik), 102.8 x 103.8 cem

Gift of Matthew and Alice Yapp

Another cloth showed the influence of designs popular on batik sarongs. The blue and white cloth with the oral bouquet motif (called buketan in batik terminology) – a sarong design that was made popular by Dutch-Eurasian batik maker Eliza Van Zuylen – is an example of this. Another altar cloth in this section worth highlighting was the only cloth in the collection that is decorated with Roman letters – Chinese characters are much more common. The letters appear to spell the surnames “Hoe” (or “Koe”) and “Sioe”, if read from the centre along the border. The middle line reads “hong” and “leng”. In Hokkien, hong is phoenix and leng means dragon; both are depicted on this cloth. The creatures are often used as symbols of a bridal couple, which suggests this cloth may have been used in a wedding.

Java, mid-20th century

Cotton (drawn batik)

Gift of Matthew and Alice Yapp

Altar cloths could also be a means of declaring political affiliation: a cloth from Yogyakarta shows human figures waving the flag of Nationalist China.

Java, Yogyakarta, mid-20th century

Cotton (drawn batik), 86 x 134.5 cm

Stamped: Batikkeru Tjie Tjing Ing, Dfogja

Gift of Matthew and Alice Yapp

Another aspect of batik altar cloths highlighted in the exhibition was the varied interpretations of common Chinese symbols. Batik cloths featuring dragons and qilins, for example, are used to show the physical differences between the two creatures. Other objects featuring these two creatures from the collections of the Asian Civilisations Museum and the Peranakan Museum were displayed alongside these cloths, so that viewers could discuss similarities, and their possible sources.

One interesting comparison worth mentioning was a Balinese palanquin with nagas – a group of serpent deities – depicted on its sides, juxtaposed with a batik altar cloth that shows elongated dragons that more closely resemble the naga than the typical coiled or front-facing Chinese dragons found on embroidered altar cloths.

The fifth and last section provided visitors with the opportunity to learn more about the rituals per- formed by Peranakans, and how different altar cloths were used for different occasions. Cloths used during Chinese New Year and other celebratory events, for example, were coloured in strong auspicious reds and generally bright hues. For funerals, altar cloths with more sombre tones were selected.

These were colours often associated with mourning in the Peranakan world – blues, purples, and greens. An example of this on display was a dark blue cloth from Singapore, which features crane and deer motifs – symbolic of longevity – as well as the cicada, a symbol of immortality.

As with the diverse designs found on them, batik altar cloths are distinctive examples of the cross- cultural interaction inherent in the hybrid identities of the Peranakans. Although these cloths – whether embroidered or batik – have long been a feature of Chinese altars, research into their past remains limited. This exhibition therefore aimed to be a preliminary investigation of these culturally and historically rich textiles, and their multiple influences.

Maria Khoo Joseph is Assistant Curator, The Peranakan Museum