History is often about presenting perspectives, and the individuals and authorities involved in producing historical accounts have different ways of describing and interpreting past events. However, history is rarely written for the mere sake of recording the past. Rather, the importance of history lies in how it serves to explain (and legitimise) conditions in the present.

When documenting historical events, historians are influenced by the complex interplay of sources as well as personal and/or institutional interests. To obtain a more holistic understanding of our past, it is important to look beyond dominant narratives, take into account history at the peripheries, adopt a multi-disciplinary approach and look at events through as many lenses as possible.

In this Singapore Bicentennial special exhibition, the Malay Heritage Centre adopts the themes of reflection and refraction as a pair of lenses to focus, clarify and contrast different perspectives. The exhibition showcases indigenous historical sources to provide counterpoints to Western perspectives and narratives of the Malay World.

In doing so, the centre hopes to present different and multiple sides of the story and to put things into perspective so that visitors can reflect on the arguments presented and draw their own conclusions.

Mapping the Malay Archipelago

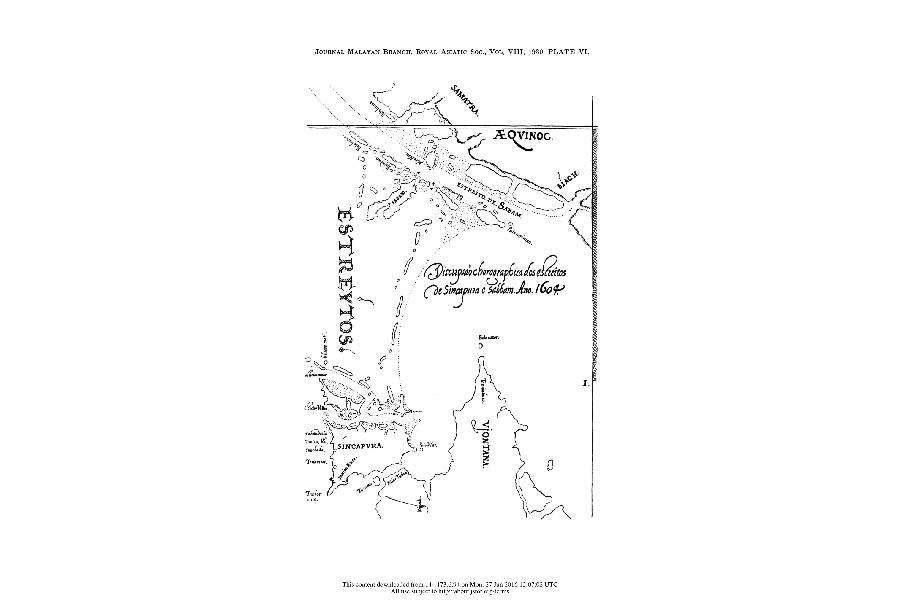

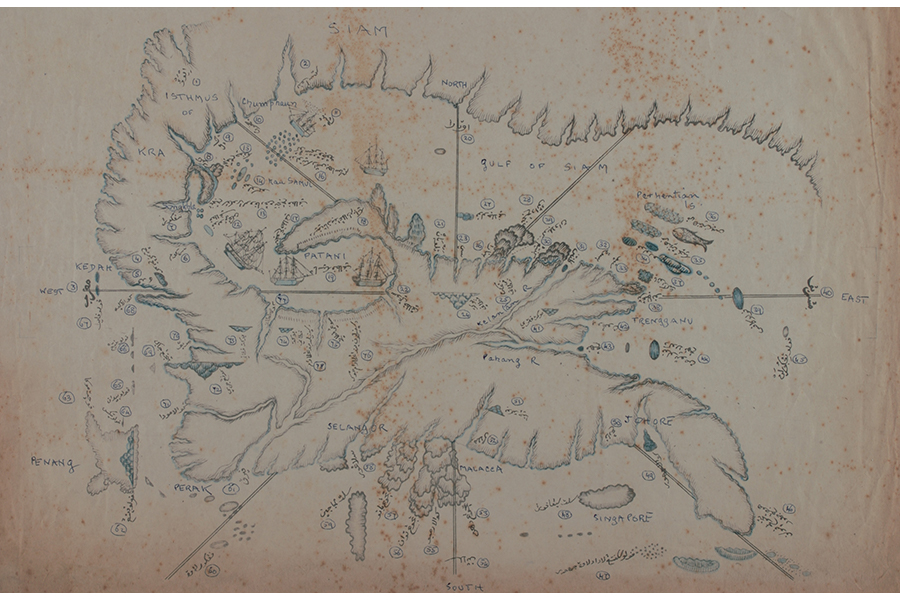

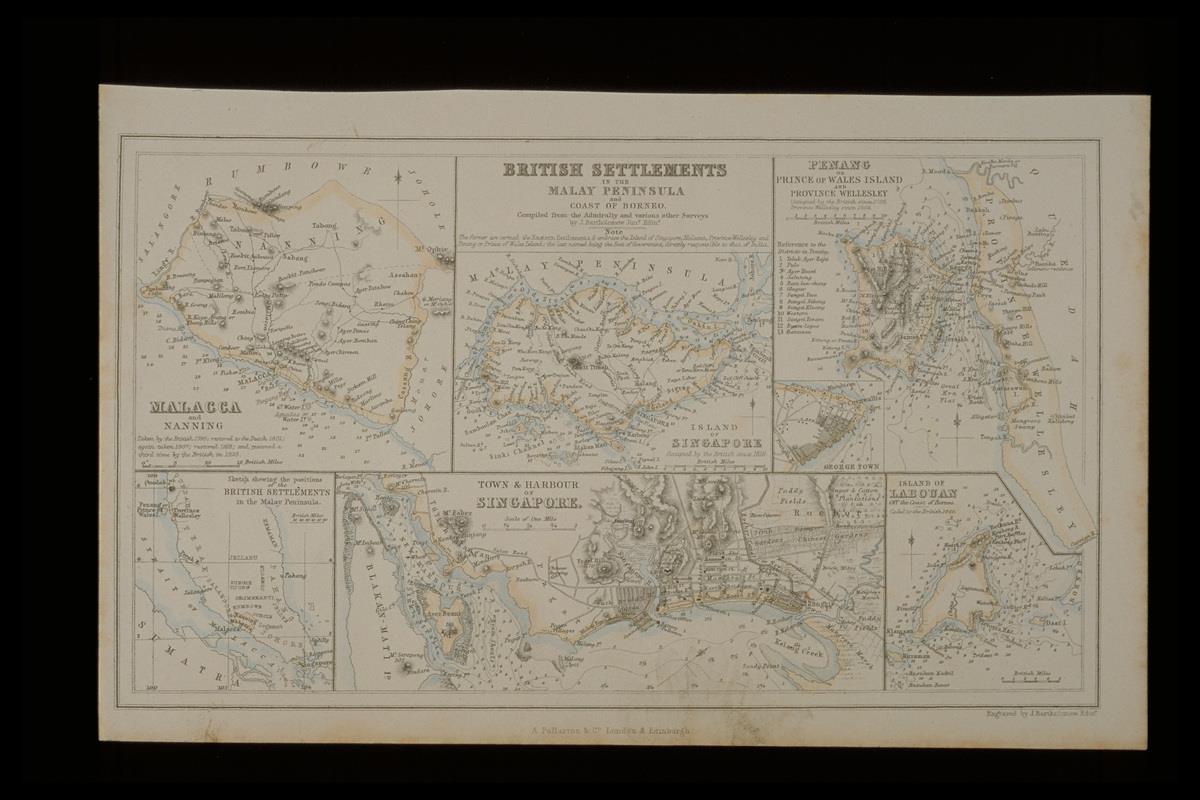

Up until the 16th century, many of the early maps of the world were speculative and inaccurate, and as a result, early trade missions were often hazardous endeavours. On these early maps, Southeast Asia was represented as little known or unexplored formations and areas. However, with increased global trade, the accuracy of maps improved significantly and they became valuable navigation aids for various maritime powers.

By the 1500s, European maritime powers were relying on maps to explore commercial interests further ‘east of the Indies’ and places in Southeast Asia became increasingly important. The following maps show how Southeast Asia, and by extension, the Malay Archipelago, have been rendered by Asian, Islamic and European civilisations as well as indigenous communities at different points in history.

Mediums of Histories

Folktales, myths and legends often serve as origin stories of countries and communities. Singapura’s origin story revolves around a prince whose curiosity led him to cross the sea, appease a sea-goddess and explore a deserted island - in the process sighting an extraordinary creature and establishing a new kingdom on the island.

In contrast to this mythical past, the official history of Singapore is pieced together from documents and records comprising treaties, surveys, government records, newspaper reports, photographs, public and private correspondences, and other ephemera from collections and archives in Europe.

Today, these documents and records as well as new archaeological findings continue to (re)inform the way Singapore’s history is studied and (re)written while earlier Malay manuscripts, sources and material culture are often studied only at the margins of historical enquiry.

The following selection of artefacts and manuscripts bring the focus back to the latter and showcases how Malay manuscripts and sources often offer an alternative lens to better understand Singapore’s past before and during the colonial period.

Melayu — Jawa: Order and Innovation

The paucity of archaeological and indigenous documentary evidence after Parameswara-Iskandar Shah fled Singapura as well as a climate change theory of a regional Little Ice Age between the 14th and 18th centuries suggest that Singapura experienced a decline during that period and bolsters the argument that the island was abandoned and played a limited role in the going-ons in the region until its revival by British colonial enterprise in the 19th century.

While this interpretation of Singapura’s past is valid to a certain degree, Singapura still retained a symbolic significance in the feudal politics of the Malay kingdoms at the time. This is because successive Malay royal genealogies since Sang Nila Utama-Sri Tri Buana have relied on narratives of the founding and subsequent flight from Singapura to legitimise the establishment of later Malay kingdoms. Subsequent rulers of the various Malay kingdoms also played the diplomacy game, using means such as exchanging gifts, paying tribute and even brokering royal marriages to establish alliances and extend their influence vis-à-vis their rivals.

Singapura’s economic importance as a collecting station and transit node in regional and international maritime routes of trade and exploration was renewed when it was incorporated into the new Johor-Riau kingdom in 1528. As contact with Western powers intensified from the 18th century onwards, the cultures and ways of life of indigenous Malay societies came under increasing scrutiny by Western social scientists and colonial administrators. These foreigners viewed and evaluated the Malay world through the lenses of Western civilisation, science and progress to such an extent that indigenous forms were generally deemed as inferior to those in the West.

Orang Atas Angin: Folk from Above the Winds

The arrival of Europeans in the Malay world is often presented as heralding a significant new chapter in the history of the region. In contrast, indigenous sources such as Malay manuscripts depict the arrival of the Europeans as a minor event within the expanded history of the Malay world.

In these indigenous sources, European arrivals are further identified not by their nationalities but by broad cultural identities such as “Rum”, “Peringgi”, “Orang Puteh” etc. Collectively, the Europeans were described as hailing dari atas angin or “from above the winds” (referring to countries that lay west to the Nusantara) and the term seeks less to identify the Europeans than to convey the position of the indigenous peoples vis-à-vis the Europeans.

The following prints highlight some of these early encounters between the indigenous groups in the Malay Archipelago and the Europeans, and showcase some of the literary archetypes of the latter who arrived in the region. These archetypes reflect the Malay community’s own views and impressions towards foreigners and refracts the notion that the indigenous communities were unaware or had little opinion of these arrivals from the west.

Sites and Straits

The Malay world did not always exist as discrete and separate political territories. Up until the 19th century, the geographical boundaries of the Malay world were informed by its own political logic – one where kingdoms, territories and people regularly shifted, in accordance with the waxing and waning of political influences within the Malay court.

The constant shift in geographical boundaries throughout the different periods is captured in cartographic and seafaring manuals from the region, in which borders are not fixed. Rather, various sites and straits are identified in order to facilitate and mirror movements through the region.

When the Dutch and the British arrived in the 18th century, they were required to refer to these indigenous sources in order to navigate the region – but not before eventually dividing the Archipelago along colonial boundaries.

The following artefacts and images present different perspectives of Singapore according to both indigenous as well as colonial conceptions of space.

Polities and Forests

In 1849, Malacca-born writer Munshi Abdullah reflected on some of the changes in Singapore shortly after the arrival of the British: “Forests have become nations, whilst [other] nations have become forests”. These changes to the natural and physical environment arose in part due to the colonial impulse to survey, map and document the local flora and fauna. From the works of British naturalist Alfred Russel Wallace to ethnographer Walter William Skeat, there are many examples of colonial studies into the naturistic realm of the Malay world.

However, as the various artefacts in this section show, knowledge of the natural environment was not the sole reserve of the European administration but also reflect indigenous attitudes towards and mastery of the natural environment, and how the colonial administration sometimes relied on and/or obscured such examples of indigenous expertise relating to flora, fauna and supernatural phenomena in order to assert European influence in the region.

Encountering the West

At the turn of the 18th century, Singapore was located in the heart of a power struggle that took place between the Dutch and the Malay world, as well as within the Malay court.

Within the Johor Sultanate, power was split between a faction led by the Bugis, and a faction led by other members of the court. This power struggle was complicated by the entry of Dutch and British forces into the region in the late 18th century, whose interests in the region manifested in the conquest of Malacca and parts of the Riau Islands, amongst other things.

Amidst this political landscape, Temenggong Abdul Rahman was said to have moved to Singapore in 1818 following a fall-out with Raja Ja’afar in Riau regarding the issue of colonial involvement in the region. It is within this context that the British East India Company, and Sir Stamford Raffles arrived in Singapore.

Tales of Our Shores

The establishment of a British trading post in Singapore in 1819, followed by the 1824 Treaty of Friendship and Alliance has foregrounded much of present-day understandings of trade, sovereignty and politics in Singapore. These treaties cemented Singapore’s eventual position as a British colony while eclipsing Singapore’s historical and cultural links to the wider Malay world.

Fortunately, these links are preserved in folk tales, literary manuscripts, documents and artefacts found across the Malay peninsula and Archipelago. Composed of both tangible and intangible mediums, the aforementioned historical sources also rarely remain unchanged over time, as new discoveries and insights are bound to emerge which may challenge and/or enrich one’s understanding of history, and by extension, one’s identity.

The Singapore Bicentennial offers Singaporeans with an opportunity to revisit inherited narratives and to refract these narratives through the lens of other perspectives – in this case, perspectives from the Malay world. In this concluding section, artefacts from more recent times are featured in order to illustrate how history is still constantly being revisited, (re)presented, refracted and reinvented.

Outdoor Installations