Changi Prison was designed to be a maximum security prison to house up to 600 criminals sentenced to long-term imprisonment in British Singapore. The remaining structures of the original prison – the entrance gate, wall and turrets – stand as an enduring symbol of the suffering of those who defended Singapore and the tumultuous years of the Japanese Occupation (1942-1945).

The Incarceration Systems of Early Colonial Singapore

Two decentralised systems of incarceration co-existed in Singapore between 1825 and 1873 – the Convict Prison which was supervised by the head of the Public Works Department and the Civil Prison which was managed by the High Sheriff. The Convict Prison at Bras Basah housed convicts who had been transported from India and the Civil Prison at Pearl’s Hill held local offenders awaiting trial. By modern standards, prison discipline was lax, allowing for infractions such as jailbreak.

Reforms were introduced after 1871, when a Prison Discipline Commission was convened to review prison issues in various British colonies. The commission published a report in 1872 which laid the foundation for a more organised prison administration. This translated to improvements in Singapore’s prison system, such as the Prisons Ordinance of 1872, which established the office of the Inspector of Prisons to oversee all jails in the colony, formalised regulations for prisons management, and established a more rigorous framework for prison discipline.

However, prison overcrowding continued to be a problem and the new Criminal Prison at Pearl’s Hill, which was completed in 1882, only managed to temporarily alleviate overcrowding. The pressing need to relieve prison overcrowding resulted in the construction of Changi Prison.

Changi Prison: A Maximum Security Prison

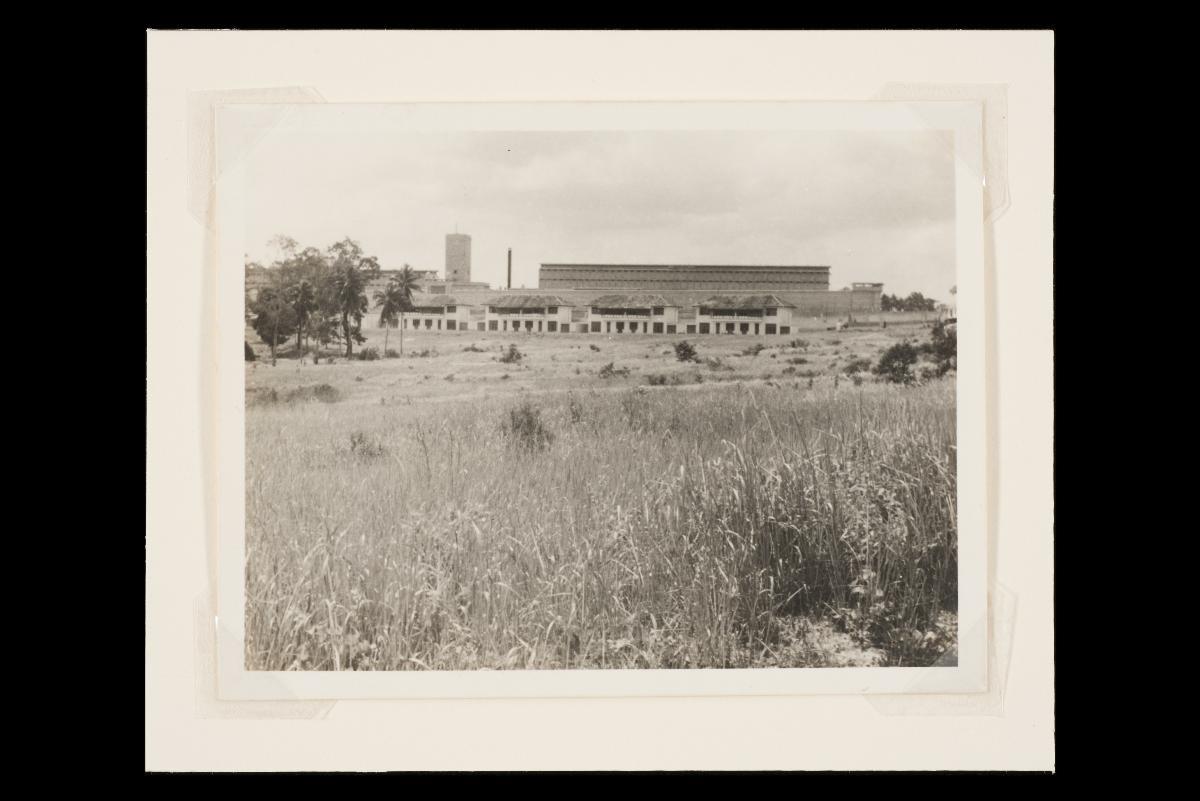

Completed in 1936, Changi Prison was described as the most modern institution of its kind in the East, boasting a comprehensive alarm system and electrical lights in its cells. It became operational on 4 January 1937, with the transfer of long-term prisoners from Pearl’s Hill Criminal Prison (later known as Outram Road Prison) which was then used to house short-term convicts.

Changi Prison was designed to be a maximum security prison to accommodate up to 600 criminals sentenced to long-term imprisonment in British Singapore. These were prisoners serving sentences of more than 15 months for crimes ranging from theft to attempted murder. The steel and concrete facility was enclosed in a high perimeter wall (of more than 20 feet in height) which made escapes impossible. It was designed with four turrets that functioned as watchtowers overlooking the prison compound. Access to the Prison was via a double-leafed steel entrance gate.

The Prison also exemplified a ‘telephone-pole’ layout plan which was commonly adopted for prisons constructed during the late nineteenth and twentieth centuries. It comprised two four-storey blocks of prison cells branching out from a central covered corridor which facilitated wardens’ quick access to the blocks.

Japanese Occupation: Prisoner-of-War Camp

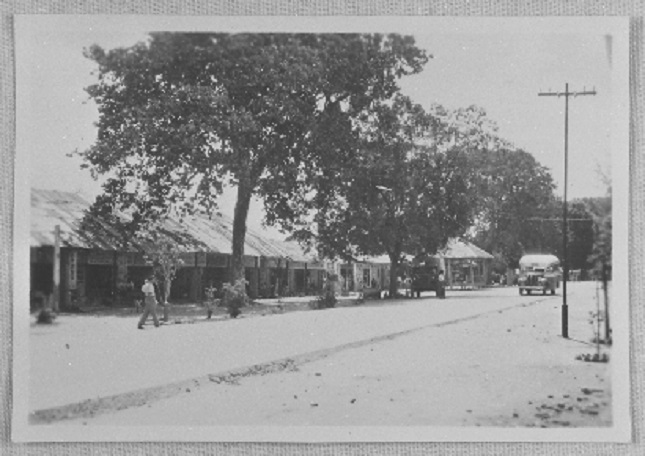

After Singapore fell on 15 February 1942, with the British surrender formalised at the Ford Factory, the entire Changi area became the principal Prisoner-of-War (POW) camp in Southeast Asia. This area encompassed Changi Prison and Kitchener, India, Roberts and Selarang barracks. It also served as a transit camp for POWs who had been captured in Java and Sumatra, before they were transported to other parts of the region.

Changi Prison was converted into an internment camp for civilians and POWs – a well-known stage in the Prison’s history. On the morning of 17 February 1942, European civilians were rounded up on the Padang and marched to Changi. More than 2,500 civilians and POWs, including the entire British civil service, were packed into Changi Prison. Temporary shelters were constructed to provide additional accommodation and internees were separated into two groups: women and children stayed in one block while the men were housed in the other three. The internees included then-Governor of the Straits Settlements, Sir Shenton Thomas, British, Australians (including former Australian Foreign Minister Alexander Downer’s father), New Zealanders, Dutch, Americans and locals.

Life in Changi POW Camp

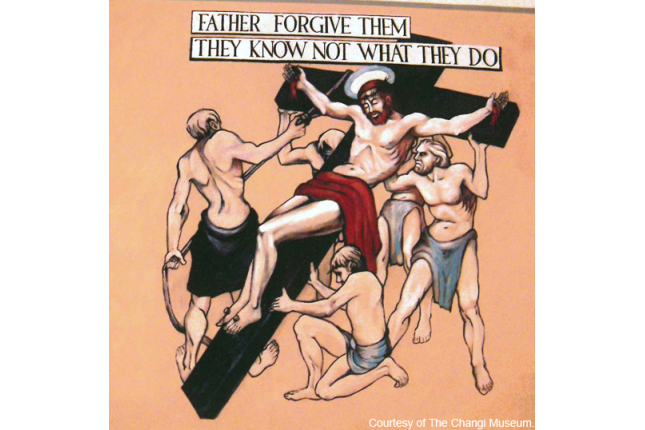

Due to the shortage of Japanese personnel, internees had partial control over camp affairs, subject to the final authority of the Japanese officer-in-charge. This allowed them to initiate a variety of activities to cope with incarceration – including the publication of a few newspapers (Changi Guardian, Changi Times and Pow-Wow), cricket and soccer matches, and entertainment by the Changi Concert Party.

Some internees were also involved in the children’s education throughout internment. The POWs overcame shortages by making their own supplies: soap was created from palm and potash, and wooden clogs replaced rotted boots. Internees also had to grow their own crops for self-sustenance, due to the food shortage.

Double Tenth Incident and Later Years of the Occupation

The internees also endured overcrowding, malnutrition, and diseases such as beriberi, malaria and dysentery. They were also subjected to punishment for disobeying camp rules. The ill-treatment of internees also worsened after the ‘Double Tenth Incident’ on 10 October 1943. On that day, the Kempeitai (Japanese military police) raided the cells to ferret out POWs who were suspected of being involved in the destruction of Japanese ships at Keppel Harbour in Operation Jaywick (26-27 September 1943). The interrogation and torture the POWs were put through claimed the lives of 15 men.

Living conditions in Changi Prison deteriorated as the Occupation wore on. Many internees were reduced to skin and bones due to the worsening food shortage. By May 1944, there were over 5,000 prisoners packed into poorly ventilated cells. The POWs had to erect attap huts in the prison courtyards, to mitigate the severe overcrowding. This was despite the civilian internees moving out of Changi Prison to make room for military POWs from the various barracks in Changi and those who had returned from constructing the Thai-Burma Death Railway. Towards the end of the war, the extreme scarcity of food forced the POWs to turn to a range of wildlife, including sparrows and rats, to supplement their diet.

The POWs were released after the end of the Second World War on 6 September 1945, six days before the Japanese signed the surrender document in the Municipal Building. From then until 1947, Changi Prison was the venue for several military courts and those convicted of war crimes against the POWs and civilians were hanged there. The Prison returned to civilian control on 15 October 1947.

Post-War Singapore

In the post-war years, Changi Prison resumed its function as a civilian prison and went on to be associated with events in Singapore’s progress towards independence. In October 1956, several members of the People’s Action Party (PAP) were arrested for their involvement in labour strikes and detained in Changi Prison. This group included Mr C. V. Devan Nair, Mr Lim Chin Siong and Mr Fong Swee Suan. When the PAP won the 1959 Legislative Assembly General Elections by a landslide, Mr Lee Kuan Yew made the group’s release a condition before he would agree to form Singapore’s first elected government. After successful negotiations with then-Governor of Singapore Sir William Goode, over 2,000 party members and supporters greeted the men when they were released from Changi Prison on 4 June 1959.

Preservation

Much of the original Changi Prison made way for a new prison complex in 2004. Key architectural features, namely the entrance gate, a 180-metre stretch of the prison wall, and two corner turrets have been retained and collectively gazetted as Singapore’s 72nd National Monument.

Our National Monuments

Our National Monuments are an integral part of Singapore’s built heritage, which the National Heritage Board (NHB) preserves and promotes for posterity. They are monuments and sites that are accorded the highest level of protection in Singapore.