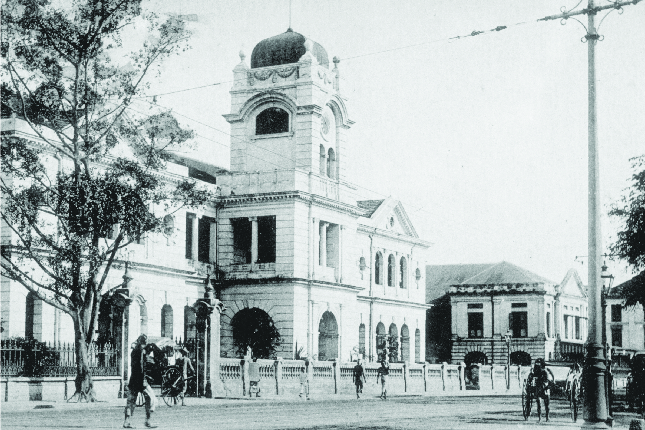

Once known among older Singaporeans as “Yit Hor Mata Chu” (Number One Police Station), the Central Police Station was a prominent landmark along South Bridge Road. Located in the heart of what was known as the ‘Greater Town’ south of Singapore River, it witnessed the transformation of the city as well as the challenges to law and order as Singapore thrived and developed. The Central Police Station was the base to police secret societies that dominated Chinatown for decades.

Policing the ‘Greater Town’

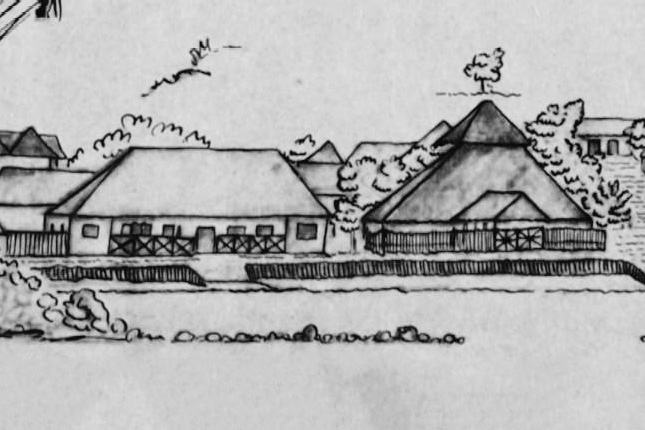

Originally the site of Singapore’s first civil jail (as opposed to convict jail that housed convict labour from abroad), the building which used to stand on this ground was converted into the Central Police Station in 1849. The civil jail was located in what European observers considered the ‘native’ quarters of Chinatown (together with Kampong Glam and Little India), in contrast with the ordered and tidy colonial district north of the river. Colloquially, the area, together with other precincts south of the river from Boat Quay to Tanjong Pagar, was known as the ‘Greater Town’ (大坡,or Dua Poh in Hokkien). It was a commercial centre unmatched in prosperity compared to other parts of the island. Yet, it was also teeming with disease, refuse, gangsters and vice. Kreta Ayer for instance, was described by a Chinese traveller in 1887 as a place filled with people, "restaurants, brothels and theatres" and yet "where filth and dirt are hidden".

A Symbol of Authority

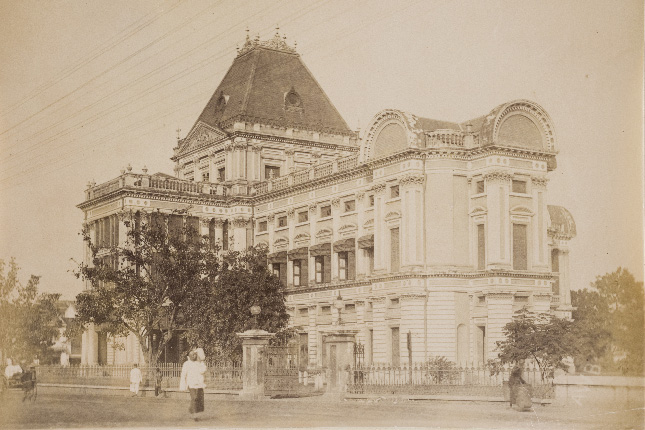

It housed the office of the Police Commissioner (later known as Inspector-General of Straits Settlements Police), barracks accommodation for officers, and the Police Courts before the courts moved into a building of its own across the road in the 1880s.

The Police were not mere law enforcers but also mediators between the colonial government and the local population. Maintaining order required a delicate balance among the needs of different segments of the community. There were instances when clumsy law enforcement led to violence. In 1872, the Superintendent of Police, who was new to the post, issued an order to clear the hawkers off the streets as they obstructed the roads. Coolies saw this as unreasonable because patronising roadside stalls was part of their daily lives. Their quarters were often too small and did not have cooking facilities. Furthermore, many Chinese earned their living as stallholders. Taking their discontent to the streets, they forced shops to close and attacked the Police and passers-by with stones, even besieging the Central Police Station. Order was only restored after the regulation was withdrawn following a consultation between the colonial authorities and leaders of the Chinese community.

After the War

By the 1930s, order in the city had improved – the operations of brothels had become illegal, opium dens reduced in number, and secret societies were under heavy surveillance. However, the aftermath of the Second World War led to a resurgence of gang activities in Chinatown. Social conditions deteriorated with high unemployment, poverty, and political uncertainty. Furthermore, Chinatown’s aging five-foot ways were cramped, overly populated, and run-down. In these conditions, secret societies proliferated.

The Central Police Station during these years became a base from which anti-secret society operations were carried out. A common practice in the 1950s or 1960s was for gangs to collect protection money from those in their territories. They harassed the hawkers who thronged the roads around People’s Park during Lunar New Year, on top of collecting $10-$15 a month from them. To combat the gangs, officers patrolled late into the night at the areas where the gangsters struck. In 1948, Police gate-crashed a gang initiation ceremony. It resulted in the arrest of 88 people and some triad initiation paraphernalia seized.

By the 1970s, the landscape of the city had been transformed. New residential neighbourhoods were built outside the city and the older parts of town were redeveloped. Central Police Station too, having played its role in securing law and order, was demolished in 1978 as part of urban redevelopment.

In The Vicinity - Vices & Secret Societies in Chinatown

After Singapore was founded as a British trading port in 1819, the number of immigrants arriving in Singapore increased rapidly. In a Town Plan drawn up by Lieutenant Philip Jackson in December 1822, the area south-west of Singapore River had been designated as the “Chinese Campong”. This later expanded into the general area known as Chinatown, which by 1836, had become the largest district with more than 13,700 settlers.

For much of the 19th century, the British adopted a laisse faire approach towards the increasingly sprawling and vice-ridden town. The Chinese were left largely under the control of their “Capitans” or clan leaders who were mostly secret society headmen. The unregulated approach was open to abuses and led to dire social consequences and the rise of crime associated with secret society activities. Almost all the Chinese belonged to secret societies where their headmen had absolute power over all the members. It was estimated that by 1831, when the police strength was only 18, there were already about 1,000 secret society members.

Clamping down on secret societies activities

By the mid-19th century, the peace of the town had been frequently disrupted by street riots arising from feuds among members of the secret societies. The Police resorted to using headmen of secret societies as special agents during the disturbances to restore peace. However, it became evident that the Police needed to be armed with legal powers in order to control the secret societies more effectively.

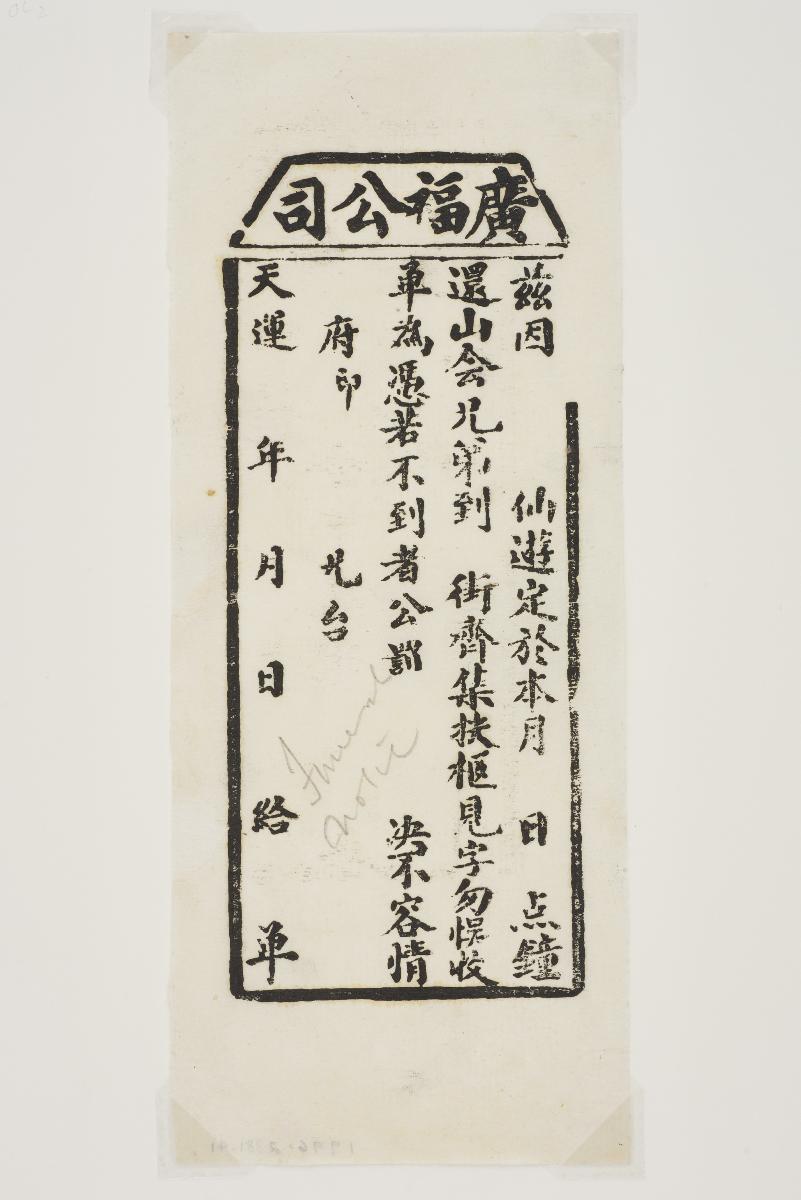

Amidst the worsening crime situation perpetuated by secret society members, the Suppression of Dangerous Societies Ordinance was enacted in 1869, requiring societies and associations with ten or more members to be registered with the Police. A total of 10 Dangerous Societies, 618 office bearers and 12,371 members were registered in the first instance. A second registration was done in 1871–2 with 12 societies and their headmen signing the register. The Ordinance enabled the Police to have constant supervision and control over the movements of these registered individuals.

By the early 1870s, the Police had managed to end the open feuds amongst secret societies. The threat of banishment under the Preservation of Peace Act 1867 also helped to bring the lawless classes under subjection. However, despite their outward subservience, the Police were well aware of the power of secret societies’ headmen to mobilise their members to mount a revolt at the slightest provocation.

In the ensuing years, more legislations were enacted in an attempt to tighten the noose on the secret societies but some were counter-productive. The Societies Ordinance of 1889 that gave police the power to outlaw secret societies only served to drive the societies underground. New and smaller groups also emerged alongside some of the traditional ones that were undeterred. They registered themselves as recreational groups, taking advantage of the loophole in the law that exempted societies formed for “recreation, charity, religion and literature”. Some of these recreational clubs continued to be active even after the Second World War.

Secret society activities reached a peak in the 1920s, and Singapore acquired the unsavoury reputation of being the “Chicago of the East”. In 1930, the Detective Branch (now Criminal Investigation Department or CID) was reorganised into specialised sub-branches to tackle crime and vices. Under the new arrangement, the supervision of Cantonese, Hakka, Hailam, FuChow, Teochew, Hokkien, Henghui and Hockchia secret society records were carried out by different dedicated sub-branches. In August 1930, the government also began restricting Chinese male immigrant numbers. There was no limit on immigration of women and children. Even up to the outbreak of Second World War, the Police were still combating crimes connected to secret societies like gambling and trafficking of women and girls.

Battling Secret Societies after the War

After the Second World War, there was a resurgence of secret society activities. Commissioner of Police (1946–1951), R.E. Foulger, noted it was a “gangsters’ holiday” as armed hold-ups and street battles involving shoot-outs between police and gangsters became rampant.

In late 1945, “Gangs” was established as a sub-branch in the Police Force. In the month of November 1945 alone, police conducted 21 raids against organised gangs, breaking up two large and dangerous gangs. In two of the raids, the police were fired upon by gangsters. On another occasion, a police patrol car was fired upon while chasing a car suspected to be conveying armed gangsters. As a result of the constant raids, it was reported that “all organised gangs of any size had ceased to exist by the middle of November. However, gangs involved in looting, pickpocketing and extortion continued to trouble the police. By 1947, crime showed an increase again over the whole island. The inability of the police to charge members of secret societies openly collecting money from shopkeepers allegedly for prayer meetings also affected the morale of the police.

In the 1950s, secret societies also entered the political fray when the communists and political parties like the Kuomintang began courting their support. During the Legislative Assembly Elections of 1954, 1955 and 1957, gangs hired by rival candidates disrupted the campaigns.

The Police also uncovered links between secret societies and labour unions. In May 1955 the leader of the Hock Lee Bus Riots was found to be a People’s Action Party (PAP) member as well as a leader of “18”, one of a secret society gang. During the Chinese Middle Schools Riots, there were 256 secret society members among the 375 students arrested. To curb the growing influence of secret societies, police launched Operation Dagger in 1956 and intensified the operations in 1957 to conduct spot checks and screenings of suspicious persons.

In 1958, the Commissioner of Police chaired a government-appointed committee to combat secret society activities. In August that year, new powers were given to the Police when the Criminal Law (Temporary Provisions) Ordinance was amended to provide for the preventive detention without trial of persons associated with criminal activities for up to six months.

In 1959, the Police also set up the Phantom Squad, later called the Special Squad comprising specially trained plainclothes police officers to deal with gangs assembling for a fight. It was met with much success but was soon disbanded in early 1961, the same year that police launched Operation Senjata. More than 1,900 policemen from divisional stations and reserve units, and members of the Volunteer Special Constabulary were mobilised to conduct surprise checks, road blocks and special patrols. Within a week, 4,420 persons were checked on, 165 persons brought into the CID headquarters for screening, 1 gangster detained, as well as the arrests of a wanted thug, an opium smoker and two persons found gambling in public. It resulted in an immediate drop in crime and secret society riots.

Due to its success, Operation Senjata was resumed in 1963, and then again in 1983 and 1984. By the 1990s, the power and influence of secret societies had been successfully curtailed. The gangs of today are but a pale imitation and mere shadows of the secret societies’ notorious past.

Behind the Spruce

Like other ethnic districts, Chinatown has been transforming progressively since Singapore’s independence in 1965. While much of the squalor have now been supplanted by the colourful façade, modernised shophouses and gentrified side streets and alleys, the stories and tales of Chinatown’s chequered past remain very much alive.

Carpenter Street

This part of town, west of South Bridge Road, was developed with the clearing of the marshes here in the mid-1840s. During this time, the physical development of Chinatown started to take off, as more land leases and grants for homes and trade were awarded.

The widespread influence of secret societies in the early 1800s was evident in early street names. Carpenter Street was originally known as Ghee Hok Street. China Street, in nearby Telok Ayer, was known as Ghee Hin Street. These secret societies started out as legal clan associations, organised along kinship and dialect groups, that the British relied on to govern the immigrant populations. New arrivals would approach these clans for assistance in a wide range of matters such as finances, accommodation, jobs, and their social and cultural life. The Ghee Hin was the first association to be established in Singapore in 1820. Many others followed including the Ghee Hok in the 1830s-50s. These were 2 major clans in the 1860s. However, the clans’ involvement in illegal vice activities and level of influence eventually led to them being outlawed in 1890 as secret societies.

Before they were outlawed, clan associations were allowed to operate lodges in association buildings. It is likely that the streets were named as such due to the presence of clan buildings along them. Colonial records show that the Ghee Hok’s kongsi house was located at No.25-4 Carpenter Street in the 1860s – 1880s. Later on, secret societies went underground and were housed in coolie quarters (known as pangkeng or room). These pangkengs were run by unemployed hooligans who looked to recruit vulnerable groups of people for their means. Their main sources of income was operating gambling dens, selling opium, or collecting protection money from those residing in the territory of the pangkeng. The decentralisation of secret societies meant they could evade authorities more easily.

Hong Kong Street

Hong Kong Street was renowned for underworld establishments, with several brothels, opium dens, and taverns. It used to be part of the red-light district in the “Greater Town” area, along with North Canal Road, Upper Hokkien, Chin Chew, and Chin Hin Streets from 1850-80. Cantonese women, who only received Chinese clients, resided on this street. It was reported that there were 45 brothels on this street in 1877, and that the Ghee Hok collected protection money from them. The red-light district would later move several blocks down into the Sago, Banda, and Spring Streets in Chinatown in the 1890s.

Prostitution in Singapore used to be commonplace in the 19th century, due to the city’s gender imbalance. This trade was heavily controlled by secret societies who were not only involved in trafficking women but also the operation of brothels in Singapore. Samsengs (or gangsters) from secret societies were deployed at brothels to enforce control over the sex workers or deal with unruly patrons.

No. 1 Trengganu Street

Life for sex workers was tough. Many were sold into the trade from an early age, with little hope for escape. It was common for sex workers to suffer and die from venereal diseases, fatal fights resulting from business rivalry, alcoholism and drug abuse. Many prostitutes committed suicide – by overdosing on opium or ingesting poison, or by hanging or slitting their throats and, in one gory account, being burnt alive – because they had no chance of ever leaving the brothel.

In September 1898, a brothel keeper and two other persons were tried for abducting and wrongfully confining a young woman. The victim and her husband, Liong Ah Kwai, had come to Singapore in search of employment. Liong ended up in jail after being wrongly accused of theft as part of an elaborate conspiracy to separate him from his young wife. His wife was sold for $100 by the captors to a brothel. The girl jumped to her death from the second storey window of No.1 Trengganu Street where she was confined, preferring death to being forced into prostitution. She was only 18 years old.

North Canal Road

This historic road used to be known as Kau Kia Ki (Hokkien for “the side of the little drain”), named after the adjacent Singapore Canal constructed in the 1800s to drain the swamps where the financial district now stands.

The shophouses along this road was home to a multitude of wholesale traders selling produce. Operating alongside them were vice activities in its many forms. The Hok Hin secret society, the third strongest after Ghee Hin and Ghee Hok in the 1860s, had their place of meeting here. The Hok Hin was known to be a wealthy society, with a large reserve fund which enabled it to provide banking services such as remittance and loans for its members. Tay Hoh Swee (Bukit Ho Swee named after him) was recorded as a headman of the society.

People’s Park

The Park Road riot on the night of 3rd March 1908 was recorded as one of the notable disturbances that year. The pre-arranged fight at People’s Park, between the “36 Friends” and “Pig Basket Friends” secret societies, ended with one stabbed to death and five wounded.

A crowd of people was listening to a storyteller at People’s Park when two rickshaws pulled up, one loaded with sticks. At about 9pm, the fight broke out when someone shouted “Pah” (meaning strike). Police in the Lower Barracks at the foot of Pearl’s Hill rushed out after hearing the commotion outside. They saw more than 300 men fighting with sticks and other weapons.

At the trial, Police Prosecutor Detective Inspector Frayne tried and convicted four men.