Weaving Ketupat

Ketupat is a rice cake wrapped with coconut leaves. Rice is a staple food for many communities in Southeast Asia. For the Malay community, there are several ways that rice is served- and ketupat is one of the ways where rice is cooked in small pouches made from young coconut leaves. The use of coconut leaves is a commonly found example of traditional food packaging found in the region.

Ketupat comes in various shapes and sizes. The manner of weaving the ketupat is the same, and the difference lies in the complexity of each weave, particularly the kepala (head) and ekor (tail). The more complex ketupat can use up to four leaves.

Traditionally used in religious ceremonies in the Malay world as a form of offering, the name ketupat is believed to be derived from the Javanese words ngaku lepat, which may be translated as “admitting one’s mistakes”. The crossed weaving of palm leaves is said to represent mistakes and sins committed by human beings, while the inner white rice cake is said to represent purity and deliverance from sins after observing the Ramadan, prayers and rituals.

In Singapore, ketupat is often prepared as a celebratory food, commonly enjoyed by families during the Hari Raya celebrations where they are served with a variety of other dishes.

Geographic Location

Variations of ketupat can be found in Southeast Asia, including in Indonesia, Malaysia, Singapore and the Philippines.

Natural materials have been used for food packaging for generations in many communities in the region, and the coconut leaves and banana leaves are the leaves that are more commonly found and used in Singapore.

The weaving and preparations of ketupat often takes place in households, before festivities and celebrations. Usually about a week before Hari Raya, young coconut leaves would be collected or sold in markets.

Communities Involved

In Singapore, the weaving and eating of ketupat is mostly associated with the Malay Muslim community, though ketupat is also consumed and enjoyed by many beyond the community and across the population.

Associated Social and Cultural Practices

Although ketupat can be eaten at any time, it is closely related to celebration of Hari Raya Puasa and Haji in Singapore, as the celebratory atmosphere of the festivals is said to give a different kind of pleasure as an occasion to savour the delicacy with loved ones.

Ketupat weaving used to be a family activity when children were taught how to make it and when family members competed with one other to weave the most ketupat. Ketupat pouches were also woven from colourful ribbons which typically adorn Malay homes during festive periods. Due to the level of difficulty and practice required for mastery, the weaving of ketupat is increasingly becoming a rare activity.

The weaving of ketupat involves the following steps: First, the leaf is separated from the spine. The spine is also useful as it can be made into part of a broom after it has been smoothened. The more pliable part of the spine could also be used as a string for tying the ketupat. The weaver will have to wrap one part of the coconut leaves onto the right and left hand as many as four times, and this will determine the size of the ketupat. Next, the weaver has to hold the end of the leaf on the right hand and left hand tightly, and insert the leaf coil, right over left, continuing with the next like weaving a mat. When the weaving is completed, the ketupat can be tightened by pulling gently on the “tail”, to tighten it.

Rice is put into these woven pouches, and the ketupat is boiled for several hours, and cooled before serving.

The Malay Muslim community believes that the way to eat the ketupat is not by peeling away the coconut leaves but by cutting them into halves.

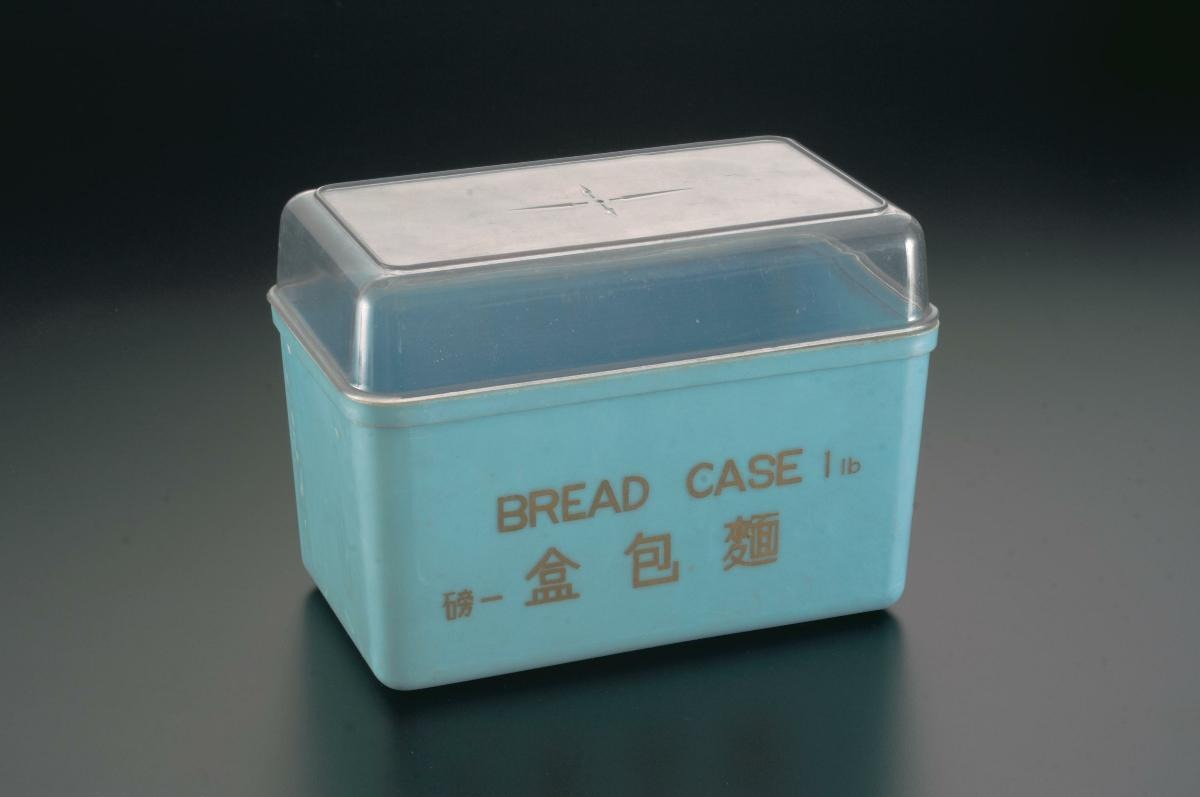

In Singapore, ketupat is particularly associated with satay and its accompanying peanut sauce, but traditional ketupat is hardly found at satay stalls now. Instead, those are commonly available are either wrapped in plastic or banana leaves. These days, plastic-wrapped ketupat, also known as “instant ketupat” can be bought easily, while pre-woven empty ketupat pouches can also be purchased for quicker preparations.

Experience of a Practitioner

Mdm Anita binte Tompang started learning the skills of weaving ketupat at the age of 11 from her mother. Now with 50 years of experience – she has been keeping this tradition within her family of five by leading them in the weaving of ketupat by hand every Hari Raya (roots.gov.sg) for over 20 years. Mdm Anita and her family typically prepare and weave the ketupat leaves on the first day of Ramadan, and prepare the rice to be used in the ketupat in the early morning of the next day. While Mdm Anita and her daughters fill up the ketupat with rice, her husband and son prepare a charcoal fire to boil the ketupat in a pot filled with water and pandan (pandanus; an aromatic tropical plant prized for its sweet floral fragrance) leaves to give the ketupat a distinct fragrance.

Mdm Anita then serves the ketupat as a dish to break-fast with during the month of Ramadan – a practice which she and her family take pride in and look forward to, and which she believes gives meaning and joy in the celebration of Hari Raya for her family. To Mdm Anita and her family, the weaving of ketupat is regarded as a symbol of love and to strengthen family connections. Mdm Anita continues to put in concerted effort to transmit this knowledge and to cultivate the skills and appreciation for ketupat weaving to her children, in hopes that the tradition will continue on to her grandchildren as well.

Present Status

Community members have observed that the sustainability of this tradition is affected not just by the modern lifestyle but also the attitude of the community about tradition and the maintenance of traditional practices. For Madam Anita’s family, the tradition of weaving ketupat continues to be transmitted across generations, with determination and enthusiasm. Mdm Anita has also persisted in her efforts to keep this craft alive within the wider community in Singapore, by teaching and promoting ketupat weaving through public workshops, and by experimenting with and applying a range of different ketupat weaving forms and techniques through participation in the Craft X Design (nhb.gov.sg) programme.

References

Reference No.: ICH-076

Date of Inclusion: October 2019; Updated March 2023

References

Ibrahim, Fuziah and Jamaluddin, Rusli. “The Malay Traditional Leafen Art Food Packaging, paper presented at The 5th Tourism Educators' Conference on Tourism and Hospitality, 3-4, Universiti Sains Malaysia, Penang, Malaysia, August 2007.

Rianti, Angelina, Novenia, Agnes E., Christopher, Alvin, Lestari, Devi, and Parassih, Elfa K. “Ketupat as traditional food of Indonesian culture”, Journal of Ethnic Foods 5 (1): 4-9, March 2018.

Yousof, Ghulam-Sarwar. 2015.One Hundred and One Things Malay. Singapore: Partridge Publishing, 2015.

Hamid, Abdul Ghani. “Dari anyaman ketupat ke lontong segera”. Berita Harian, 17 October 2002.