Roti Prata

Roti prata is a type of flatbread with origins from India. The word “roti” is derived from the Hindi language, meaning bread, while “paratha” means flat. Flatbreads are found in different forms in different parts of Asia, and the version in Singapore is believed to be a result of culinary inventiveness by Indian migrants who came to the Malay Peninsula. In Singapore, roti prata has been localised to the extent that innovative recipes with ingredients like durian, red bean and kaya have emerged.

Geographical Location

Roti prata is available in different forms across Asia, in countries such as India, Myanmar, Sri Lanka, Thailand, Malaysia, and Singapore. These regional variations come in the form of different names, tastes and ingredients. While the standard ingredients used to make roti prata — flour, egg, salt, water, ghee, condensed milk, and sugar — are generally the same everywhere, extra ingredients may be added as fillings. In Singapore, many different ingredients can be added based on individual preference — from the more typical egg and onion to more creative options like milo powder, kaya, and red bean.

Communities Involved

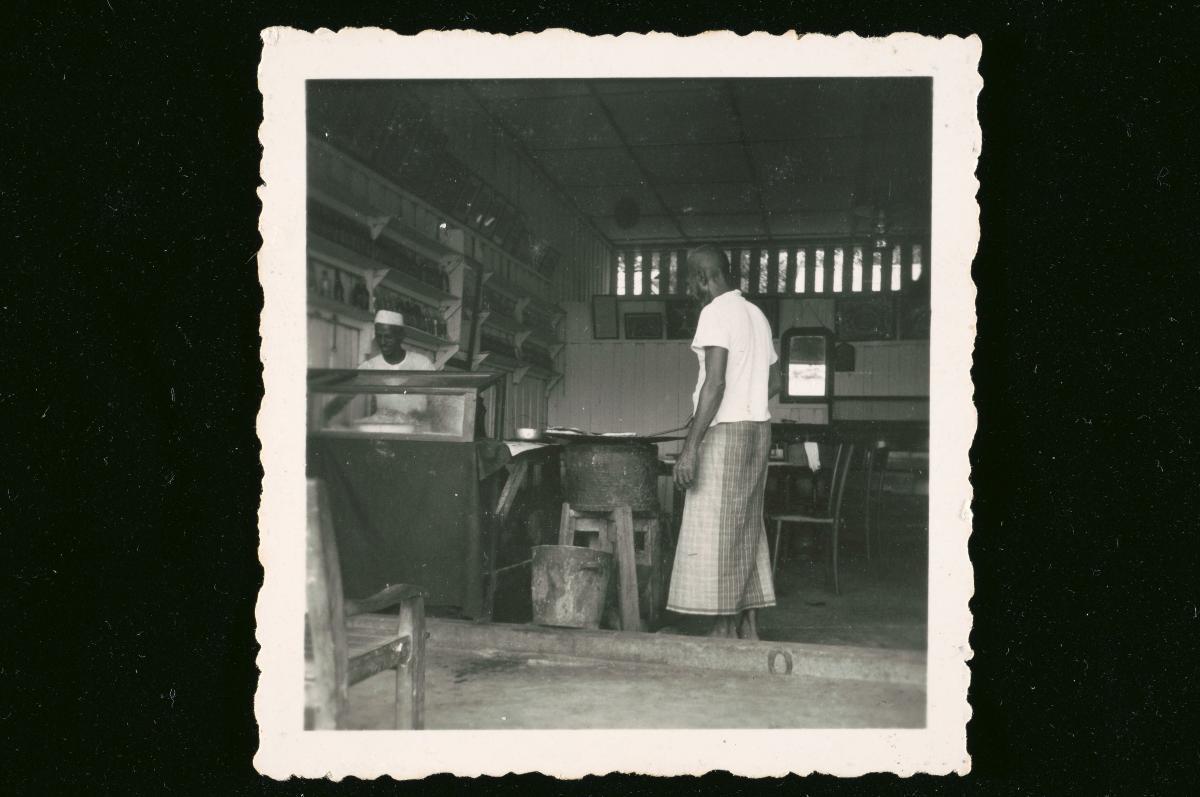

Roti prata is usually prepared by Indians or Indian Muslims at neighbourhood coffee shops or restaurants, and is enjoyed by different ethnic communities in Singapore. Roti prata is highly popular as a breakfast dish though it can be consumed at any time of the day as seen from 24-hour restaurants such as R K Eating House and Al-Ameen Eating Corner.

Associated Social and Cultural Practices

The art of making roti prata requires knowledge of traditional recipes and practical skills in preparing the ingredients. Recipes are sometimes passed down orally, or through training under a skilled practitioner.

Roti prata is made from dough, which is prepared by mixing plain flour, water, egg and salt. It is kneaded and then divided into small parts, flattened slightly before ghee or margarine is added. The dough is left to rest, possibly refrigerated, for about 5-8 hours or overnight.

To prepare the dough before cooking, the dough ball is rolled using a rolling pin that has been oiled into a circle on a greased work table. The dough is then sprinkled with ghee before it is rolled up into a long rope, coiled into an S-shape, then set aside for one hour before it is rolled again into a circle. Lastly, the dough is flattened on the work table and flipped until it is paper thin and about four to five times its original size. Flipping the dough is considered a most difficult step, requiring much skill. The stretched dough is folded into a rectangle or a circle, and then fried over medium heat on a griddle which has been greased with vegetable oil or ghee. The roti prata is cooked until it is crispy on the outside and soft on the inside.

Experience of a Practitioner

Mr Somasundram Mohgan runs a popular roti prata stall, Mr and Mrs Mohgan’s Super Crispy Prata. He started making roti pratas in 1982 at the age of 16, learning the skills from his mother. He then worked in different places—the Satay Club, Haig Road Food Centre, Poh Ho Restaurant—before he relocated to Tin Yeang Restaurant (a coffeeshop in Joo Chiat) in October 2018. He identifies strongly with the craft of making roti prata and takes pride in his roti prata being listed as one of the best in Singapore by various food blogs and media publications.

Mr Mohgan has a 27-year-old apprentice, Mr Mohammad Jihath, who has been helping him for the last 7 years. He plans to pass on his roti prata recipes to his children and apprentices in the future when he retires. He is receptive to the different ingredients and combinations that have emerged in recent years, noting that some of the ingredients, like cheese and mushroom, go quite well together with fish curry and that sugar is a good alternative for children who cannot take curry.

Present Status

The making of roti prata is still going on strong, though Mr Mohgan acknowledges that the younger generation of locals are more interested in eating roti prata than making it. He has had problems getting locals to help with his business and knows of some stores that have closed down because they could not get enough help.

According to Mr Mohgan, anybody who is interested in learning how to make roti prata can learn from current practitioners, though it may take up to 6 months to learn how to properly make it. In his opinion, the hardest step in making roti prata is flipping the dough, and this skill is difficult to learn without the opportunity to observe an example. The correct proportions of ingredients for making of roti prata also requires some time to master.

Information about roti prata making is well documented. Cookbooks and online audio-visual materials provide information on how to prepare the dough and fry it, while many websites listed in Singapore include information on different types of roti pratas that are available.

References

Reference No.: ICH-088

Date of Inclusion: October 2019

References

Duruz, Jean. “Tastes of hybrid belonging: following the laksa trail in Katong, Singapore”, Continuum, 5: 605-618, 2011.

Henderson, J. Catherine. “Food and culture: in search of a Singapore cuisine.” British Food Journal, 116: 904–917, 2014.

Lai, Ah Eng. “The kopitiam in Singapore: An evolving story about migration and cultural diversity”, Asia Research Institute Working Paper Series, 132: 3-29, 2010.

Lee, Raymond L.M. “Malaysian identities and mélange food cultures”, Journal of Intercultural Studies 38(2): 139-154, 2017.

Pillai, Patrick. Yearning to Belong: Malaysia’s Indian Muslims, Chitties, Portuguese Eurasians, Peranakan Chinese and Baweanese. Singapore: ISEAS-Yusof Ishak Institute, 2015.

Yeo, Chris. and Joyce Jue. The cooking of Singapore: Great dishes from Asia’s culinary crossroads. California: Harlow & Ratner, 1993.