Chinese Weddings

Chinese weddings are traditionally elaborate affairs, comprising numerous ceremonies and rituals that are rich in meaning and symbolism. Many of the customs embody blessings for a happy marriage and for bearing children. They also help to reinforce the ethnic identity of the participants, especially that of dialect groups since each group has its distinct wedding practices.

Geographic Location

The wedding rituals take place mainly at the homes of the groom and bride, while the wedding banquet is commonly held at a restaurant, hotel ballroom or event hall. Some rituals take place two weeks before the wedding at homes, while the banquet is held in the evening of the wedding day itself.

Communities Involved

The families of the bride and groom are directly involved in the wedding. Other relatives and friends may help with the planning, as well as participate in some of the wedding activities and rituals.

Also involved are wedding planners and Chinese wedding speciality shops. These individuals or companies have taken over the role that was once played by professional matchmakers known as mei po (媒婆) in terms of providing knowledge of the wedding rituals and customs.

Associated Social and Cultural Practices

Most Chinese wedding practices today begin with a betrothal ceremony called guo da li (过大礼). It is held two to four weeks on an auspicious day before the actual wedding day, and involves the groom, accompanied by a female relative, bringing gifts to the bride’s family. The bride’s family then returns some of these gifts, known as hui li (回礼), to symbolise the acceptance of the marriage. They also present the groom’s family another set of gifts. This is also when the bride receives her trousseau, known as jia zhuang (嫁妝). The gifts exchanged are usually elaborate, with items chosen specifically for their symbolism. For example, mandarin oranges are given for good luck, while charcoal signifies a good life after marriage.

The next step is preparing the matrimonial bed in a ritual known as an chuang (安床). This takes place three days to one week before the wedding. The steps include covering the bridal bed with new bed linen, on which is placed a big red tray filled with an assortment of items meant to signify prosperity for the couple. On the wedding day, before the bridal couple arrive, a young boy (ideally one born in the Year of the Dragon) is asked to jump and roll on the matrimonial bed as a way to bless the couple with many children.

The night before the wedding includes a hair-combing ritual called shang tou (上头) to symbolise the couple’s transition into adulthood. The ritual takes place in the respective homes of the groom and the bride. Each of them faces a pair of lighted candles while a woman considered to have good fortune (someone whose husband, children, and grandchildren are alive) combs the hair four times and repeats an auspicious phrase each time.

On the wedding day, the groom goes to the bride’s home to bring her back to his home. But first, there is a ritual called “gatecrashing”, where the bridesmaids make the groom and his groomsmen complete a series of playful tasks before he can see the bride. As the bride leaves her home, she is sheltered with a red umbrella. When she gets into the bridal car, the bride will throw a red foldable fan known as the “Lady Fan” out of the car window to symbolise leaving negative things behind.

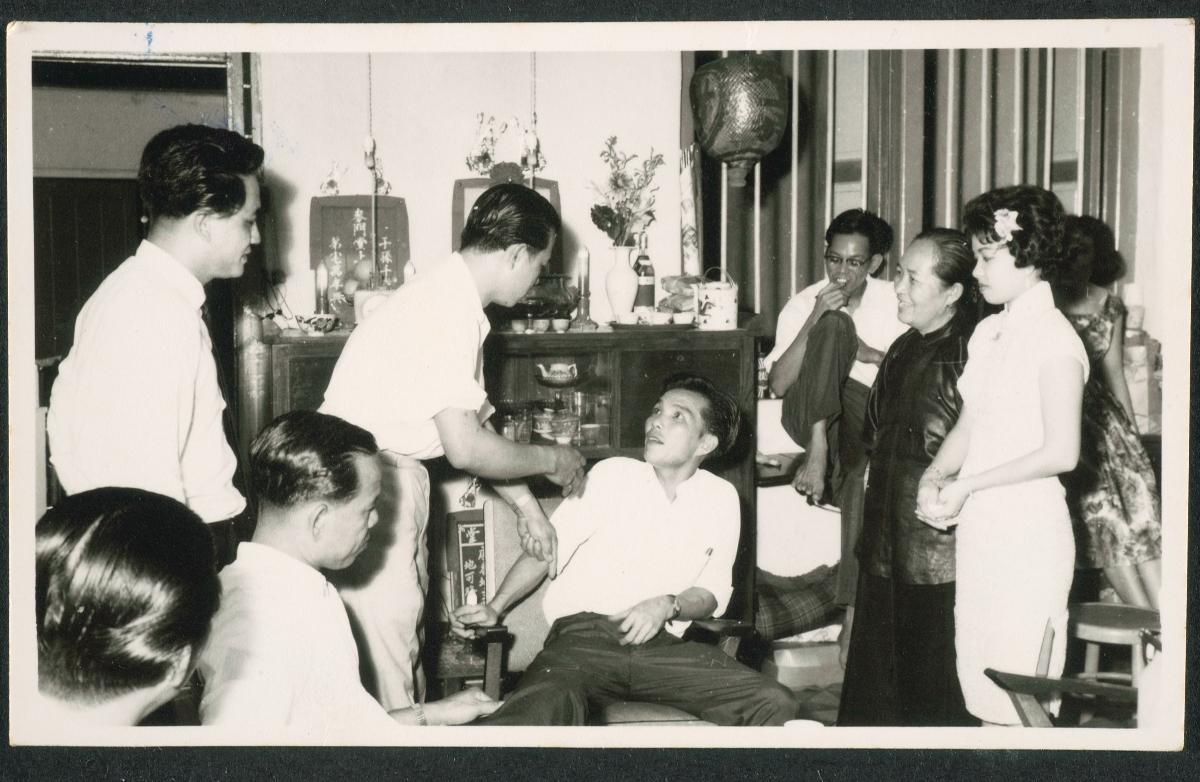

The first part of the tea ceremony then takes place at the groom’s home. If deities and ancestors are worshipped at home, the couple will pray at the family altar before serving tea to the elders of the family. The elders will give their blessings to the couple.

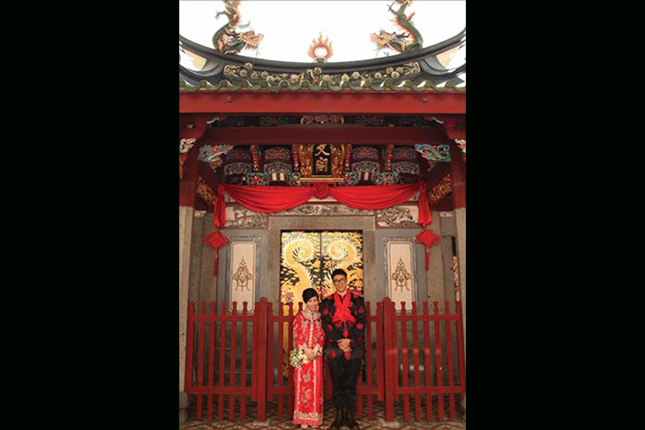

The couple then leave for the bride’s house to hold a separate tea ceremony for the bride’s family, after the bride changes into a kua (褂). The kua is a traditional red Chinese wedding dress embroidered with auspicious symbols.

The banquet is the last part of the wedding, where families, friends and colleagues will be invited to attend the event, which often takes places at a restaurant, hotel ballroom or event hall. During the dinner, the couple’s entourage is invited on stage for a toast. This is known as the yam seng, and involves the guests in the entire hall shouting “yam seng” (or “cheers”) three times as loud as they can, to congratulate and confer blessings to the new couple. The couple then visits each table and toasts the guests.

With regards to the attire on the wedding day, many couples these days prefer to wear western suits and gowns for their weddings. Some couples may retain the tradition of wearing traditional Chinese wedding outfits for rituals such as the tea ceremony, such as the ma kua (马褂) for the groom, and red qun kua (裙褂) for the bride. The red symbolises good fortune and happiness, and the embroidery work on the qun kua often features motifs of phoenix and flora patterns.

Experience of a Practitioner

Ms Rubina Tiyu has about 13 years of experience in the wedding planning industry. She shares that though couples do refer to wedding planners as a source of information for Chinese wedding practices, she feels that the most important institution involved is still the family. Ms Tiyu regards weddings as “community involvement” events where families are also involved in rituals, and in deciding the wedding practices to follow.

Ms Tiyu firmly believes that a couple should seek their family’s opinion and knowledge about marriage traditions and rituals. “I always tell the couples to ask their families because you don’t want to disrespect them at the end of the day. If they suggest one small thing that would ultimately make everyone happy, why not? Besides, I think it creates a sense of festivity as well,” Ms Tiyu explains.

Ms Tiyu explains that the different Chinese dialect groups in Singapore have their own practices and traditions. For example, among the Cantonese, the bride usually wears the qun kua (裙褂) as her wedding dress when the groom goes to fetch her. The Teochews believe that the bride should leave her home before sunrise, and thus hold the gatecrash ritual very early in the morning.

Present Status

Many couples still maintain several of the core wedding practices. Over time, modernisation, busy schedules and budget constraints have led some to the simplification of certain rituals. Some couples may also be unaware of the value or meaning behind certain Chinese wedding practices and hence do not follow them. Nevertheless, the rituals and values that have been passed down from generation to generation continues to evolve and be observed in Chinese weddings in Singapore.

References

Reference No.: ICH-017

Date of Inclusion: April 2018; Updated March 2019

References

Freedman, Maurice. Chinese Family and Marriage in Singapore, London: Her Majesty’s Stationery Office, 1957.

Heng, Terence. Making Chineseness in Transdiasporic Space: It’s a Matter of Ethnic Taste, Department of Sociology, University of London Ph.D. dissertation, 2010.

Heng, Terence. “A wedding photographer’s journey through the Chinese Singaporean urban landscape.” Cultural Geographies 19(2): 259–270, 2011.

Leong, Huan Chie. Understanding Marriage: Chinese Weddings in Singapore, Masters thesis, Department of Sociology, National University of Singapore, 2011.

Lim, Kimberly. “Wedding gatecrashers: Putting love to the test by eating Nutella from a diaper”. The Straits Times, 6 November 2016.

Singapore Federation of Chinese Clan Associations. Chinese Customs and Festivals. Singapore: Singapore Federation of Chinese Clan Associations, 1989.

Singapore Hokkien Huay Kuan. 阮这世人:新加坡福建人的习俗 (Customs by Hokkiens in Singapore). Singapore: Singapore Hokkien Huay Kuan, 2009.

Soh, Audrie. “Wedding Traditions – The Traditional Bride”, Singapore Brides, 2012, https://singaporebrides.com/articles/2012/10/wedding-traditions-the-traditional-bride/. Accessed 15 January 2018.

Tham, Seong Chee. Religion and Modernization: A Study of Changing Rituals Among Singapore’s Chinese, Malays and Indians. Singapore: Graham Brash, 1985.

.ashx)