TL;DR

The Nine Emperor Gods Festival is a nine-day celebration deeply rooted in Chinese traditions, involving rituals, temple visits, and a grand send-off ceremony. One of the largest religious festivals in Singapore, it allows followers to seek blessings and pay respect to the Nine Emperor Gods, while also serving as a time for communities to come together in self-purification and abstinence. Delving into the origins, traditions, material culture and communities associated with the festival, the Sun Yat Sen Nanyang Memorial Hall (SYSNMH) and the Singapore Chinese Cultural Centre (SCCC) co-present ‘Expressions of Devotion: The Nine Emperor Gods Festival in Singapore’ at SCCC Level 6 Creative Box, from 18 July 2024 – 11 August 2024.

Introduction

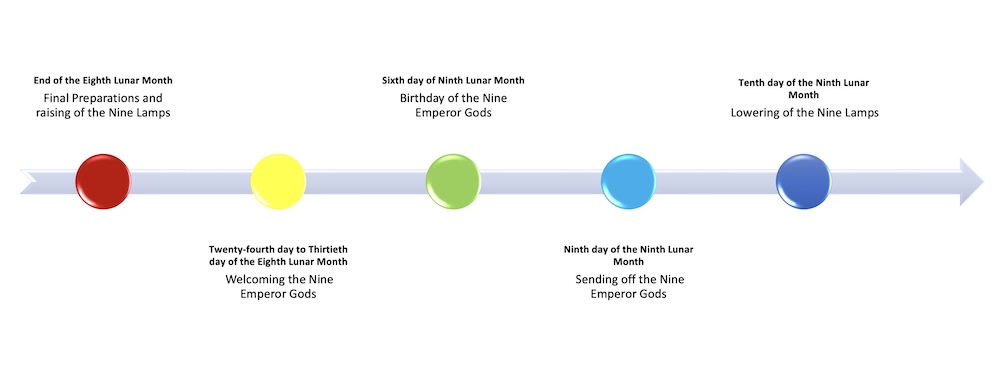

Every year, as the eighth lunar month comes to a close, the usually quiet Nine Emperor Gods Temples and their constituent communities burst into activity. Temple members and helpers converge from different parts of Singapore to prepare for the arrival of the Nine Emperor Gods. Every nook and cranny of the temple is meticulously cleaned, from religious paraphernalia to the temple facade and culinary tools. The customary red decorations are removed and replaced with yellow banners and lanterns (photo 1, 2, 3 and 4). Yellow is a homonym for ‘emperor’ and imperial power in China, and it represents the presence of the Nine Emperor Gods within the temple. Following the cleaning, the temples raise the zhai jie (斋戒 means “vegetarian diet and abstinence” in Chinese) sign. From this point of time onwards, devotees visiting and helping in the temple must adhere to a rigorous regime of vegetarianism and mental discipline. This is a significant characteristic of the Nine Emperor Gods Festival.

The Nine Emperor Gods Festival, deeply rooted in the history and communities of the Chinese in Singapore and Southeast Asia, spans nine days. It commences with the raising and lighting of the Nine Lamps and concludes with their lowering. The festival is a time for seeking blessings from the Nine Emperor Gods and for devotees to strengthen bonds of friendship and kinship through their shared devotion.

Origins

The narratives surrounding the origins and manifestations of the Nine Emperor Gods are diverse and varied. Some view them as the nine-star deities of the Northern Dipper, while others believe they are the nine brothers who resisted Qin Shi Huang’s (259-210 BCE) tyranny. One of the widely circulated beliefs in Singapore is that the Nine Emperor Gods are loyalists of the Ming dynasty (1368-1644) who were beheaded by Manchu forces.

Landscape of Nine Emperor Gods Temples

In Singapore, there are more than twenty temples celebrating the Nine Emperor Gods Festival. Among them is the Hougang Tou Mu Kung (后港斗母宫), established in 1921 and one of the oldest temples dedicated to the Nine Emperor Gods. The temple was started by a man called Ong Choo Kee in 1902, who invited the incense ashes from Hong Kong Street Dou Mu Gong (香港巷斗母宫) in Penang and enshrined them within his house. Subsequently, the shrine was relocated to five and a half milestone Upper Serangoon Road and Hougang Tou Mu Kung (后港斗母宫) was built there (currently 779A Upper Serangoon Road) in 1921.

Similar to Hougang Tou Mu Kung, some of the earliest Nine Emperor Gods temples in Singapore were founded using incense ashes from the two oldest temples in Malaysia: Hong Kong Street Dou Mu Gong (香港巷斗母宫) in Penang and Nan Tian Gong (南天宫) in Ampang. For instance, Hong San Temple (凤山宫), Shin Sen Keng (神仙宫) and Jia Zhui Kang Dou Mu Gong Feng Shan Si (汫水港斗母宫凤山寺) were established using incense ashes brought over from Nan Tian Gong (南天宫) in 1906, 1920 and the 1900s, respectively.

Another notable feature of these early Nine Emperor Gods temples in Singapore is their strong affiliation with the surrounding village communities. For example, Hougang Tou Mu Kung temple (后港斗母宫) served the Hokkien and Chaozhou communities in Hougang and Upper Serangoon areas; Kew Huang Keng (葱茅园九皇宫) served the Lemongrass Garden Kampong (near present-day Geylang Serai); Hong San Temple (凤山宫) served the Tai Seng Village; Tao Bu Keng Temple (蔡厝港斗母宫) served Sungei Tengah Village; and Jia Zhui Kang Dou Mu Gong (汫水港斗母宫凤山寺) served the Jia Zhui Kang Village. The festival was a communal event involving the entire community, with temples observing yew keng (游境, which means 'tour of the area' in Hokkien / Teochew) throughout the different communities in the village.

With the end of World War Two in 1945, the number of Nine Emperor Gods Festivals in Singapore rapidly increased. This was attributed to the establishment of new temples dedicated to the Nine Emperor Gods, as well as the adoption of the Nine Emperor Gods as the main deities of already existing Chinese temples. Many of these new temples emerged due to instructions and revelations from the deities, as evidenced in the origins of temples such as Yu Hai Tang (玉封玉海棠观音堂), Nan Shan Hai Miao (南山海庙), Leong Nam Temple (龙南殿), and Leng San Giam Dou Mu Gong (龙山岩斗母宫). For example, in 1971, Nan Shan Hai Miao (南山海庙) began hosting the festival in Jalan Ang Teng following instructions from the Dua Li Ah Pek (大二爷伯, Great Uncle and Second Uncle) deities. Similarly, Leong Nam Temple (龙南殿), initially a Guan Di temple in Geylang Serai in the 1950s, began hosting the Nine Emperor Gods Festival in the 1960s under the direction of the bodhisattva Guan Yin, who conveyed her wishes through a medium.

Following Singapore’s independence in 1965, the number of temples continued to increase, many of which were led by young leaders with dedicated followers. For instance, in 2008, Yu Feng Jiu Huang Dian (玉封九皇殿) was established by a group of young devotees. Initially located in the founder’s house, the temple later moved to Mandai Estate and then to Bukit Batok Street 23. Presently, the temple holds its annual festival near Yu Hua Market in Jurong East. Similarly, since the 2010s, Zhun Ti Tang, a Buddhist Temple, has been hosting an annual Nine Emperor Gods Festival. Initially held in the owner’s home, the festival later moved to an open space near Rivervale Plaza.

Rapid urban redevelopment has compelled many temples to relocate to new areas. Village communities have also dispersed to different housing estates. As these temples establish new communities and networks, they have also developed new traditions and practices to maintain ties with their original locations. For instance, Kew Huang Keng holds a Yew Kampong (游甘榜, meaning “procession throughout the village” in Hokkien / Teochew) on the sixth day of the festival. The procession visits makeshift altar stations in Haig Road, Geylang Bahru, Bedok, and Bedok North, where the villagers have resettled. During this event, incense is exchanged, and the palanquins bless the altar stations, symbolising the continuation of kampong bonds and ties. Below are some photos of Yew Kampong in Kew Huang Keng.

Traditions and Practices

The Nine Emperor Gods Festival starts with the receiving of the Nine Emperor Gods by a water body and the ceremonial raising of the Nine Lamps. This typically occurs during the last week of the eighth lunar month. The Nine Lamps serve to inform the heavens and surrounding area of the commencement of the festival and symbolises the presence of the Nine Emperor Gods.

The receiving of the Nine Emperor Gods is a grand affair. The temple forms a contingent comprising palanquins, an incense censer, and, in some cases, mediums. The procession goes to the beach to receive the Nine Emperor Gods, who are usually represented as incense censers and are then invited into the palanquins. Subsequently, the deities are escorted back to the temple and invited into a separate room known as the Inner Chamber (内殿), where they reside for the duration of the festival. Access to the chamber is restricted to selected individuals observing strict vegetarian diets and abstinence regimes.

Over the next few days, the temples remain open throughout the night for devotees to pay respects and seek blessings. Various rituals are conducted, including rewarding the spiritual armies (稿军) deployed to protect the festival premises, sticking strips of paper with devotees' names on the Dragon Ship to seek blessings, seeking consultations from mediums, and refilling the Nine Lamps with oil. Devotees can also cross the Bridge of Blessing (平安桥) to seek protection from misfortune. Opera and traditional musical performances are also arranged for the deities.

.ashx)

The sixth day of the ninth lunar month is widely regarded as the birthday of the Nine Emperor Gods, marked by special offerings and rituals. Daoist priests present petitions and prayers to the Nine Emperor Gods on behalf of the temple’s leadership and devotees. Among modern-day offerings is an eggless birthday cake. Additionally, temples such as the Hougang Tou Mu Kung(后港斗母宫) and Jia Zhui Gang Dou Mu Gong (汫水港斗母宫凤山寺) may also perform a separate ritual known as “Inviting Water” (请水), where water from various bodies of water is drawn and used by Daoist priests to perform purification rituals.

Visits between different Nine Emperor Gods temples, also known as “worship ceremonies” (参拜) or “offering incense” (进香), are also another key event that takes place during the festival period. Temples form an entourage bringing gifts, sandalwood, and incense, embarking on a tour to other organisations. The temples exchange incense as a gesture of friendship. Periodically, a grander scale of yew keng may take place, involving the tour of palanquins, devotees, and cymbal and drum troops.

On the ninth day of the ninth lunar month, the temples send off the Nine Emperor Gods. The incense censers are brought out from the Inner Chamber. Together with the palanquins, the sending-off contingent moves towards the sea. At the beach, the censer is carried into the sea to symbolise the departure of the deities. The ceremony concludes with the burning of the dragon ship. Below is a sequence of events during the sending off ritual.

Finally, on the tenth day of the tenth lunar month, the Nine Lamps are lowered, marking the conclusion of the whole festival.

Conclusion

The Nine Emperor Gods Festival is an integral part of Singapore's intangible cultural heritage, deeply rooted in the traditions of the Chinese community. It not only allows followers to seek blessings and pay respect to the Nine Emperor Gods, but also serves as a time for both old and new communities to come together during a period of self-purification and abstinence.

The author would like to thank the Nine Emperor Gods Festival Documentation and Research Project for the photo contributions, as well as Esmond Soh and Prof Koh Keng We for reviewing the article.

Notes

Koh, Keng We, Lin, Chia Tsun, Koh, Kah Wee Ernest, Lim, Yinru, and Soh, Chuah Meng Esmond.

The Nine Emperor Gods Festival in Singapore: Heritage, Culture and Community,

two vols. Singapore: Nine Emperor Gods Project, Singapore Chinese Cultural Centre, 2023.

Lin, Chia Tsun and Koh, Keng We. Sacred Ties: A Century of Devotion to Nine Emperor

Gods in Tao Bu Keng Temple. Singapore: Tao Bu Keng Temple, 2023.