TL;DR

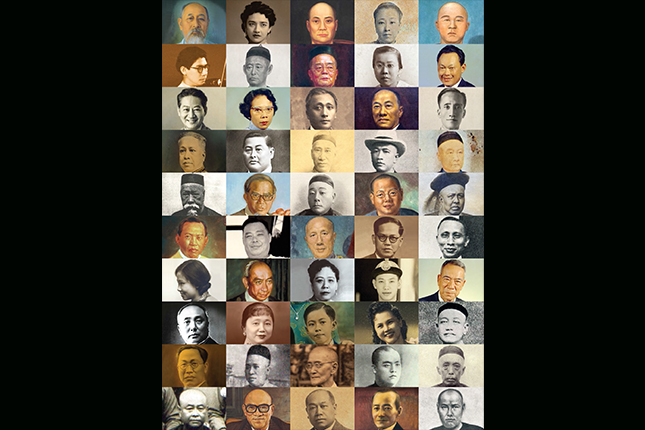

The scheduled restoration of Sun Yat Sen Nanyang Memorial Hall, a National Monument, was a chance for the institution’s team to reflect on their care and custodianship of the displayed artefacts, many of which are important to preserving the history of Singapore’s Chinese community. Tanya Singh, who worked on the deinstallation process, shares her views.As the Sun Yat Sen Nanyang Memorial Hall, or Wan Qing Yuan, closes its doors for restoration, we the staff found ourselves reflecting on the vibrant history encapsulated within its walls. This elegant villa, once the residence of prominent local businessman Teo Eng Hock (1872-1959), served as a crucial revolutionary base for Dr. Sun Yat-Sen (1866-1925) during his sojourns in Southeast Asia. It was within these walls, from 1906 to 1911 that the air crackled with whispered plans of revolution as Dr. Sun and his loyal supporters plotted to topple the Qing Dynasty, establishing the villa as the Nanyang headquarters of the Tong Meng Hui (Chinese Revolutionary Alliance).

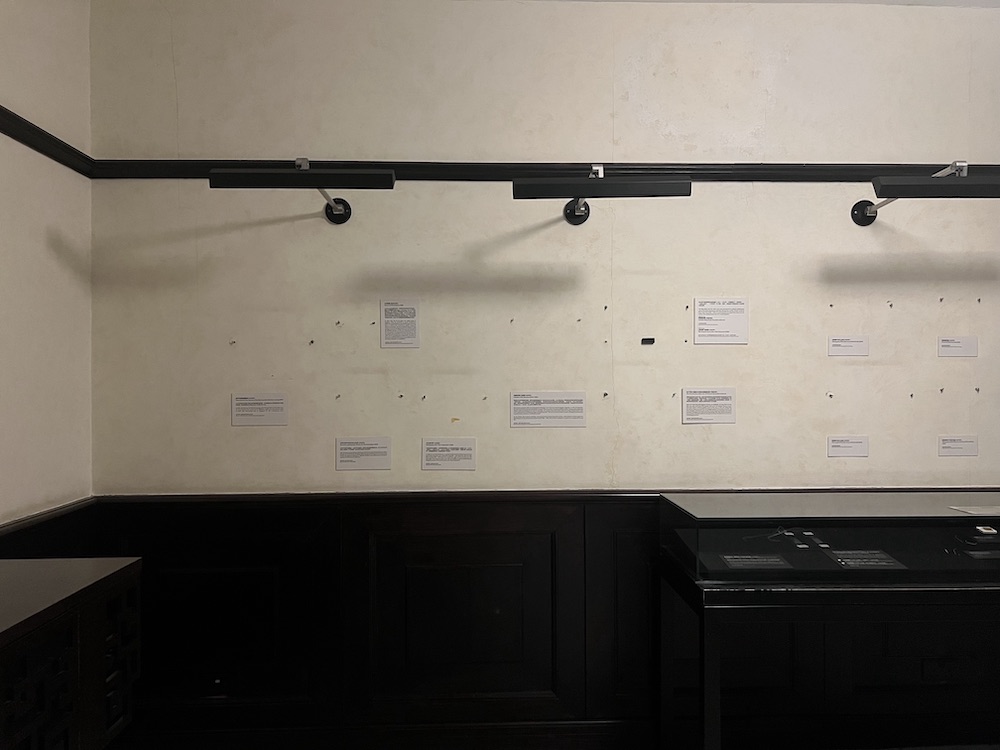

Gallery 3 after the deinstallation of artefacts from the showcases. (2024. Courtesy of Sun Yat Sen Nanyang Memorial Hall.)

The name "Wan Qing Yuan", meaning “Serene Sunset Garden”, evokes a sense of tranquillity, yet this serenity is now amplified by the absence of the gallery objects that once filled its halls with vibrant stories. The silence now permeating these rooms echoes with the ghosts of heated debates, revolutionary discussions, and dreams of a new China. These bare rooms stand as a powerful testament of how fervently the Chinese community in Singapore embraced Dr. Sun’s vision of change, their dedication etched into the very fabric of this historic villa.

The markings and nails left behind on the wall, as artefacts are deinstalled for storage during the building’s restoration. (2024. Courtesy of Sun Yan Sen Nanyang Memorial Hall.)

Packing Up a Community’s History

In preparation for the restoration and content refresh, the deinstallation process commenced on 23 September—a delicate task that took three weeks to complete. Of the 200 objects deinstalled, around 90 belonged to our National Collection. These were carefully prepared for their temporary return to the Heritage Conservation Centre in Jurong, where they would rest until the memorial hall reopens its doors. The deinstallation team approached each artefact with meticulous attention, ensuring that every piece, regardless of size, was treated with the utmost care.

Deinstallation of a grandfather clock. (2024. Courtesy of Sun Yat Sen Nanyang Memorial Hall.)

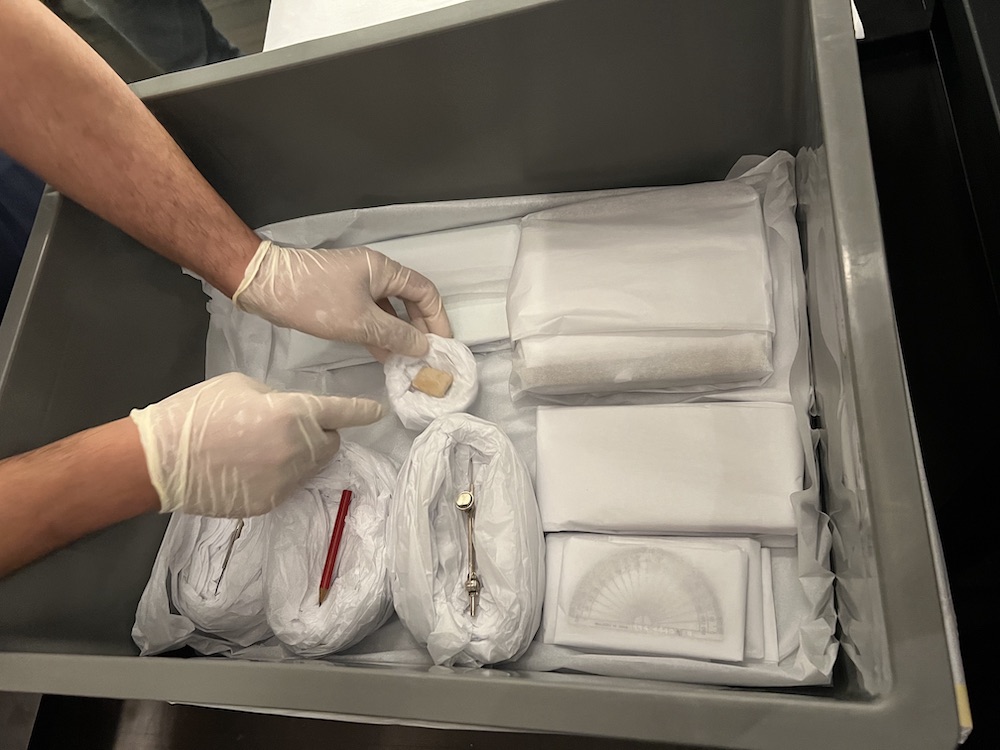

Delicate paper artefacts, representing various facets of Singapore’s Chinese community’s history, were carefully removed from display and wrapped in acid-free paper to prevent any damage during transit. In addition to the paper artefacts, the team carefully deinstalled a collection of badges from Chinese community organisations in Singapore. Despite their diminutive size, these badges carry weighty historical significance. Each badge was meticulously packed, in temporary cradles and covers made with acid-free paper to shield them from impact and moisture. Once secured in their cocoons, the badges were diligently labelled with their accession numbers preparing them for storage. . This attention to detail ensured that even the tiniest pieces would remain intact and ready for future display.

Artefacts that recreated a 20th-century schooling experience, such as a geometry box and magic ruler, are packed in acid-free paper cradles for transfer to the Heritage Conservation Centre. (2024. Courtesy of Sun Yat Sen Nanyang Memorial Hall.)

The Heidelberg windmill letterpress presented our most formidable challenge —a colossal machine weighing over 1000 kg. This machine, acquired from the Kuon Ying Press in Kampar, Ipoh, was encased in a large glass showcase that had to be disassembled. Due to its sheer bulk, the press could not fit into the elevator, necessitating its extraction through a second-floor window. The process involved creating a customized galvanised steel base to support the weight of the press, protecting the flooring with metal plates, and employing a pallet jack to manoeuvre it toward the window. Once positioned, a crane was summoned to hoist the letterpress onto a platform. It was a breathtaking sight, a dance of machinery and careful planning that culminated in its safe transfer to a truck bound for the Heritage Conservation Centre.

Dismantling the glass showcase which housed the Heidelberg windmill letterpress. (2024. Courtesy of Sun Yat Sen Nanyang Memorial Hall.)

Alongside the letterpress, a complete set of movable typesets, featuring a full range of about 100,000 Chinese characters, was also deinstalled. These typesets were arranged in four heavy trays, each weighing about 50 kg, highlighting the intricate craftsmanship of the printing trade. Before being carefully packed for transport by our art handlers, conservators examined each typeface for signs of corrosion and deterioration, ensuring that the integrity of these pieces was preserved. The typesets now lie at rest beside the letterpress, their silent presence a reminder of the artistry and dedication that once breathed life into printed words, waiting to share their stories once more.

Conservator Jingyi Zhang inspecting the condition of the movable typesets before they are packed away. (2024. Courtesy of Sun Yat Sen Nanyang Memorial Hall.)

In addition to the objects from our National Collection, several significant loans were deinstalled from the memorial hall, including personal effects belonging to Tan Chor Lam (1884-1971), a prominent businessman in Singapore known for his influential role in promoting female education. Among the items carefully removed were his elegant pocket watches, which reflected the era's craftsmanship and style, as well as his personal seal, an emblem of his identity and achievements. Each of these artefacts carry a rich narrative, representing not only Tan Chor Lam's legacy but also the broader historical context of educational reform in Singapore.

Tan Chor Lam’s pocket watch and personal seal. (2024. Courtesy of Sun Yat Sen Nanyang Memorial Hall.)

We also bid farewell to the “Harbingers of Revolution” installation, a striking piece featuring 40 galvanised steel crows suspended above the main staircase. To facilitate the removal, temporary scaffolding was erected, allowing the team to safely access the artwork. Each crow was taken down individually during a coordinated effort that showcased the team’s skill and precision.

Temporary scaffolding erected for the deinstallation of the ‘Harbingers of Revolution’ (2024. Courtesy of Sun Yat Sen Nanyang Memorial Hall.)

Personal Reflections

Reflecting on my journey in the heritage sector, I can’t help but feel a deep sense of connection to the Sun Yat Sen Memorial Hall, particularly as I lead the deinstallation process of a gallery that I once helped revamp. My first project with the museum design firm I previously worked for was project managing the redesign of Gallery 4 in this very building. Back then, my focus was primarily on design, and I did not have the opportunity to learn a lot about the intricate processes behind the installation of artefacts. Now, stepping into the role of overseeing this deinstallation, I recognize the personal growth I’ve experienced in my approach to heritage work. This moment evokes a mix of excitement and nostalgia; the silence of the empty gallery signifies a transition—a chance to create new narratives and opportunities for storytelling. It reminds me of the enthusiasm I felt when I first embarked on my career in this field, reinforcing my belief in the importance of evolving our spaces to honour the stories they tell.

As we look forward to the reopening of the Sun Yat Sen Nanyang Memorial Hall in 2027, the deinstallation process serves as a poignant reminder of the importance of preserving history while adapting to the future.