TL;DR

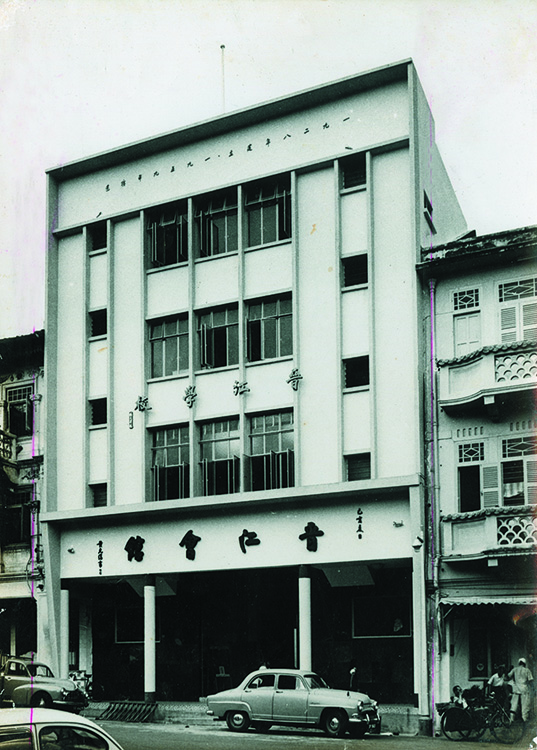

Once an important venue for aid and assistance for the swathes of men arriving from the Jinjiang (晋江; Chin Kang) county in Fujian, China, the almost century-old Chin Kang Huay Kuan association building in Bukit Pasoh now tells the story of the grim fate the men endured as indentured labourers.

Association president Jimmy Teo walks MUSE SG through the clan's new heritage gallery, and shares about his family's ties to the coolie trade.

What’s your personal story and link to the Jinjiang people and the association?

It all started with my grandfather, Teo Seow Eng, who moved to Singapore from Jinjiang county in Fujian province in the 1950s. Jinjiang is a city next to the sea. Due to internal unrest like wars and riots in the 1920s, many were desperately poor and men risked being conscripted to fight in the army. To escape these hardships, tens of thousands fled southwards to places like the Philippines, Indonesia and Singapore to find work.

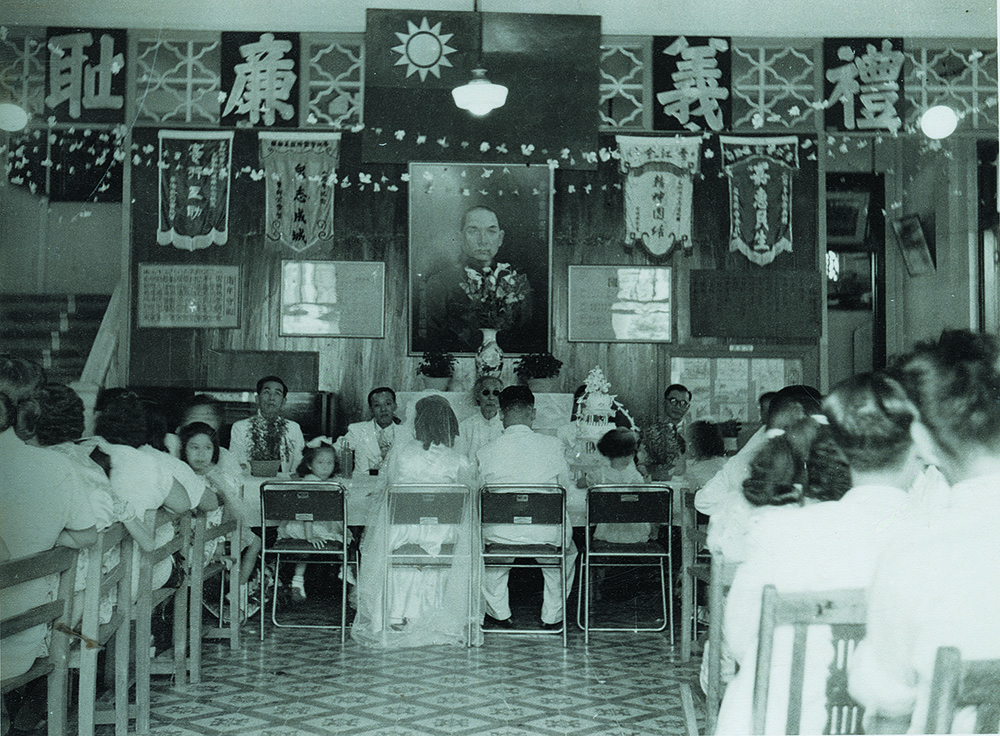

The majority of Singapore's early Jinjiang immigrants worked as indentured manual labourers, commonly referred to as coolies. The Jinjiang people formed one of the largest coolie groups in Singapore at the time, and the Singapore Chin Kang Huay Kuan was established to support them. Upon arriving in Singapore, my grandfather, who had some basic writing skills, was assigned clerical work by his bosses. Outside of his day job, he served as a community leader at the association, and helped write letters and petitions on behalf of his fellow immigrants.

Occasionally, my grandfather’s community work took him beyond the desk. Some Jinjiang fishermen, who relied on their boats for income, would sometimes drift into Indonesian waters by accident and get detained by the authorities. Many of these fishing families were extremely poor. My grandfather, out of his own pocket, would hire a boat to Indonesia, negotiate for the return of the confiscated vessel, and then arrange for it to be towed back to Singapore.

I grew up with my grandparents in an old semi-detached house in Katong. I vividly recall a commotion when I was about five, after one such successful intervention. While my grandfather was on the way home from Indonesia, my grandmother had accepted a lavish feast from the grateful family he had helped. They had sent us meat such as pig trotters, a rare luxury at the time. My grandfather was really furious that my grandmother had accepted food from such a poor family, and, true to his principles, insisted we return the spread.

When I joined the Singapore Chin Kang Huay Kuan in 1997, I began reconnecting with older clan members who knew my grandfather. That’s when I got a fuller picture of the depth of his character and the breadth of his voluntary work with the association. For example, I learnt that he personally provided regular financial aid to a family whose breadwinner was killed by a bomb during the war. He also channelled money to school building projects in his hometown to educate new generations of Jinjiang children.

“I knew there and then that I wanted to carry on my Ah Gong’s legacy. It was also because of him and the many others like him that we decided to build this gallery. Their lives were centred on quietly helping their fellow villagers, as well as the generations after them. As a clan, we feel that their stories and sacrifices are important to document and share as they offer us a window into the past and provide a more detailed picture of the Singapore story. “

A fair number of Singaporeans who grew up in the 1980s and 1990s are familiar with the coolie story, having watched local dramas which depicted their journeys to Singapore in the belly of ships for a life of toil. How would you present the story of the coolie to new generations of Singaporeans?

Unlike most workers in Singapore today, coolies had no insurance, workplace benefits, or access to physiotherapists. And they had the hardest jobs. They worked backbreaking 24-hour shifts hauling, handling and carrying 100-kilogramme loads of grain, corn, pepper, spices, tea and the like. Machines were scarce, with no cranes or robots to ease the burden on workers. There were simply no shortcuts.

At the end of their shifts, coolies returned to damp, tiny and overcrowded quarters in Amoy Street and Telok Ayer where they slept on canvas sheets on the floor.

To soothe aches and sprains, they used ointments on their joints. Tonic tincture was one of the few items they brought along with them from China. However, herbal tonics were not always effective. To dull their pain whether at work or rest, many turned to opium.

Today we’re still in contact with about 10 coolies with Chin Kang roots. Many others have passed on, which is why we put together a gallery focused on retelling the coolie story. No such dedicated gallery exists in Singapore and it’s important we capture the coolie account for new generations of Singaporeans to familiarise themselves with a key chapter of our history.

What are some of your favourite coolie artefacts in the gallery? What do they tell you about the coolies’ work ethic?

We've a weather-beaten hat on display, someone's old blue work overalls, and a typical wooden box which coolies used to store their handful of belongings. On colder nights, they used gunny sacks as blankets.

Coolies were paid based on the number of bags they carried. Upon ferrying one bag, they were given a stick which they could exchange for a few cents at the end of each shift. There were three types of coolies who worked along the Singapore River—the ones who loaded items from the big ships onto smaller ships, another group which took over the journey of a product from smaller ships to land, and a third group which hauled items from land to the warehouses in the area.

We are very blessed because some of our members who were former coolies donated their tools and equipment to our association before they passed on. They used iron needles to mend torn gunny sacks and shovel pipes to collect samples and examine goods.

Many of the items on display tell the story of a hard, cruel life centred on work and very little rest and recreation. Our artefacts are accompanied by text, images and videos to help visitors vividly experience and intimately connect with the tireless spirit of Singapore’s Jinjiang pioneers.

This project was supported by the National Heritage Board’s Major Project Grant.

The Chin Kang gallery is located on the fourth floor of the Chin Kang Huay Kuan (Clan Association) building at 29 Bukit Pasoh Road, Singapore 089843 and is open every Tuesday, Thursday and Saturday from 10 am to 3 pm. Admission is free.