TL;DR

The iconic sarong kebaya is a shared heritage of nyonyas and other communities in Southeast Asia, but during the colonial era, Peranakan Chinese ladies also embraced global fashion trends, occasionally donning Western dresses. Early 20th-century images from Java reveal how nyonyas wore fashionable white lingerie dresses in a unique way. This article explores the impact of Western lingerie dresses on Peranakan women's self-expression. It highlights the hybridity of Peranakan fashion and emphasises the importance of understanding the community's diverse cultural responses in defining their unique identity.

Dr Bahar Gürsel, Department of History, Middle East Technical University (METU/ODTÜ), Turkey

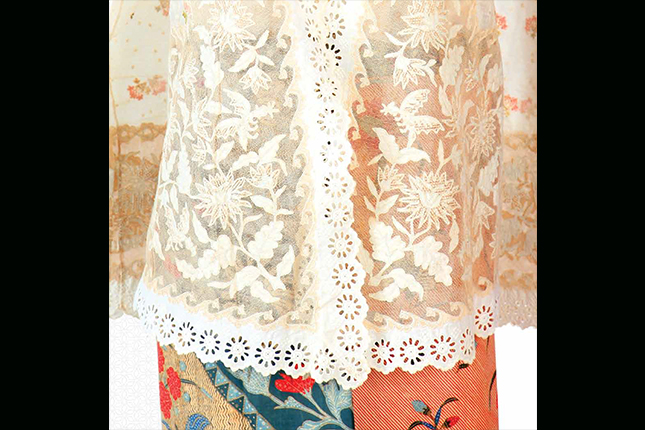

The sarong kebaya is often considered the iconic attire of nyonyas (in particular, Peranakan Chinese women) in Southeast Asia, although it is a shared heritage of the region. Yet, during the colonial era, nyonyas also followed global fashion trends, and occasionally put on Western dress “to suit the prevailing style” in their surroundings.2 The most significant evidence for this can be seen in some early 20th century images from Java. By exploring a number of portrait photographs from the collections of the Peranakan Museum, this article explains how nyonyas wore fashionable white lingerie dresses in their own unique ways.

Worldwide admiration for the lingerie dress

The naked dress is widely recognized as one of the most striking global fashion items that dominated 21st century red carpets. These see-through gowns are designed in different colours and cuts, using plenty of lace, mesh, net and other transparent and translucent fabrics. While garments worn by Marilyn Monroe, Jane Birkin, and Cher in the 1900s are often considered iconic examples of naked dresses, the true precursor of this fashion trend was the muslin gown of Marie Antoinette, the Queen of France. The simple and light chemise à la reine of the 1780s was made of imported cotton instead of French silk and signified the start of an “‘underwear as outerwear’ style revolution” in Europe and England.3 Many things changed after the Revolution, but the impact of this new garment endured until the 1820s. The resurgence of the lingerie gown in the late 19th century saw the delicate and embroidered "invisible" white gown extend its influence globally.

The lingerie dress was the principal garment for warm weather and climates in the Edwardian wardrobe. As a representative of the daring “underwear as outerwear” vogue, it highlighted a woman’s “femininity, charm, and grace,” and used white and pastel fabrics such as linen, cotton, or muslin that were trimmed generously with “embroidery, lace, or net inserts.4 Lightweight and delicate lingerie dresses were embellished with various ornaments like ruffles, frills, ribbons, and sashes. Women from different social classes wore these gowns in their everyday lives. Handmade lingerie dresses were very expensive and were “richly embroidered” whereas, after the 1890s, the ready-made versions were cheap and were sewn by using “lower quality washable fabrics”.5 Machine-made laces became the symbols of “the democratization of the lingerie dress” by enabling women from all social classes to fulfil their dream of “floating on a cloud of lace”.6

In overseas colonies—where the weather was mostly warm and humid—Western-style attires became emblematic especially of local elite women’s socio-economic and educational backgrounds. In this context, wearing lingerie dresses also became a way to exhibit privilege and sophistication for the women of the colonised lands. However, these women did not simply imitate their Western counterparts when wearing these gowns—they created their own unique styles by mixing and matching their vernacular accessories with the immensely popular lingerie dresses.

Nyonyas and their lingerie dresses

Until the early 20th Century, baju panjang—a loose tunic worn over a sarong—was the traditional attire of nyonyas. However, they abandoned it in the Dutch East Indies around 1900 in favour of the refined and sleek white lace kebaya and floral sarong.7 In Java, according to the 1872 statute, “it was illegal to appear in public attired in any manner other than that of one’s own ethnic group”. 8 This law was designed to prevent the natives from dressing like their colonisers. Peranakan women were not allowed to put on Western attire until 1910, when the newly-issued Dutch Nationality Law “declared that all children born of parents vested in the East Indies were Dutch subjects even if not Dutch citizens”. 9 Hence the Peranakan Chinese became Dutch subjects, and accordingly “adopted European dress for public occasions”. As such, the European and Eurasian women in the region adopted the lace kebaya and batik nyonya with European floral motifs. Their Peranakan counterparts in Java and later in the Straits Settlements devotedly embraced this Europeanised version of sarong kebaya.10

Peranakan scholar Peter Lee highlights how photographs from the past portray how Peranakans “dressed in different modes, and sometimes in diverse kinds of hybrid modes, when it suited them to do so”.11 Moreover, reporting on fashion steadily increased during the Edwardian era, and renowned journalists’ articles in fashion magazines “encouraged readers to view fashion as a guideline rather than a prescription for dress”. In this respect, the “Design and Fashion” column of The Straits Times extravagantly presented the lingerie dress to its female readers in the region:

Prominent among the most remarkable successes of the season are those soft lingerie gowns in the finest of white muslins and French lawns…Cut on those long, straight lines which give the favourite silhouette of the moment, already scoffingly described as length without breadth, these lingerie gowns are made as a rule in the form of Princess robes, with the skirts and bodices most ingeniously connected by waistbelts of insertion, lace, and embroidery, so that they have the appearance of a garment which is made all in one piece from throat to feet. The long, trailing skirts are trimmed with embroideries of a more or less elaborate description, crossed and recrossed by many lines of transparent lace insertion. For wearing under these lingerie gowns special slips are provided made in white batiste for the more economical, or in white soft silk or satin for those who can afford such luxuries. These lingerie gowns will certainly prove a good investment, since they are very easily washed or cleaned, and most useful. 13

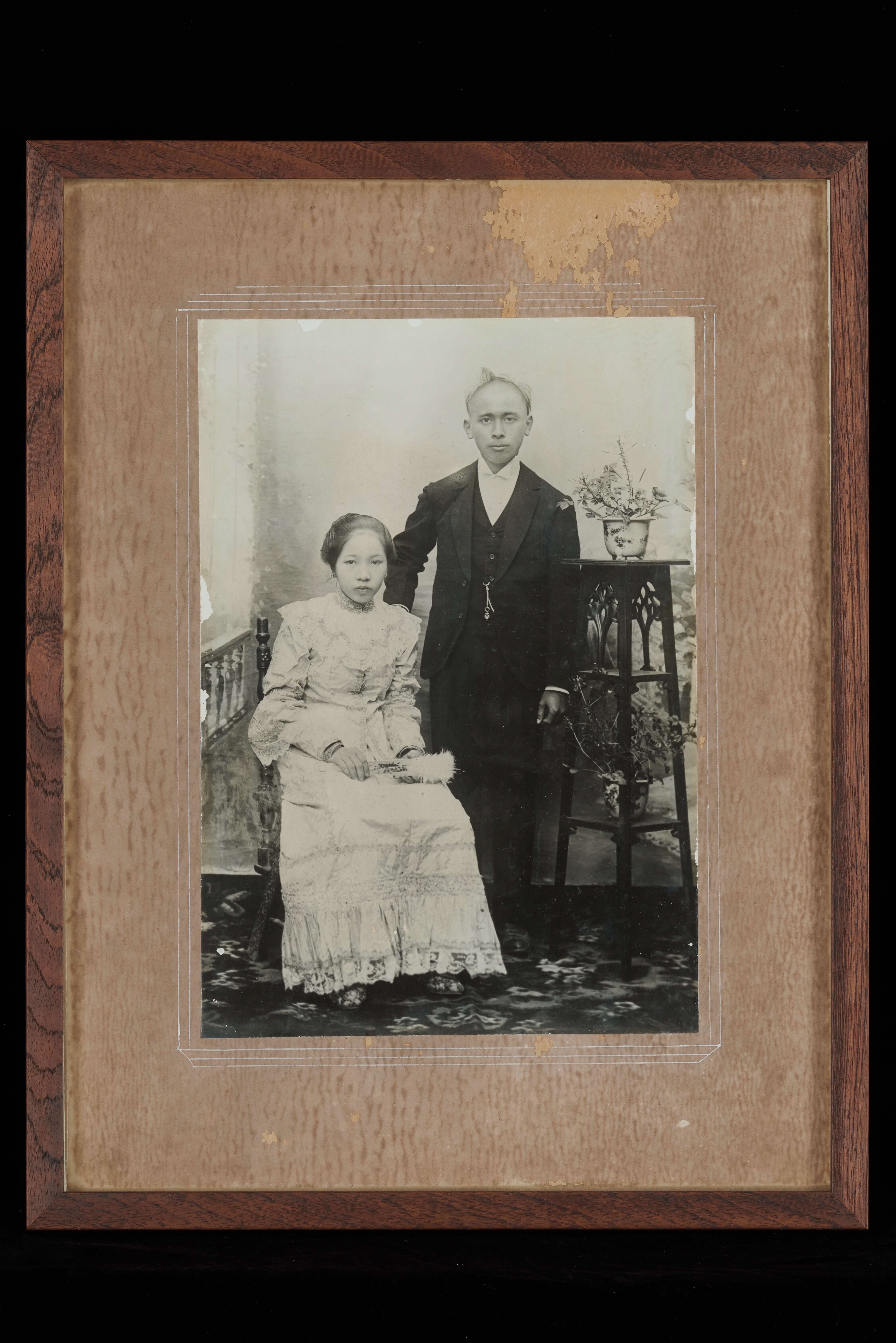

The Europeanised sarong kebaya was an indicator of the hybridity in Peranakan style of clothing and fashion, yet not its sole manifestation. Some studio photographs taken in Java during the early decades of the 20th century reveal that quite a considerable number of women fancied wearing the fashionable lingerie dresses of the era. In Figure 1, for instance, the nyonya sits on a chair in her lace-trimmed two-piece costume. The pleats and flounce arms give the outfit a fashionable appearance, and the floral motifs on the self-patterned white fabric are hazily recognisable on the upper part of the dress. Although the dress looks plain, different types of waved braids on the stylish mandarin lace collars and skirt show that a considerable amount of time was spent on embroidery. The husband's three-piece black suit reminds us that Peranakan men "had already adopted Western-style clothes" during the early half of the 20th century.14

Framed studio photograph of Peranakan Chinese couple, Java, around 1910s.

Collection of the Peranakan Museum, Gift of Mr and Mrs Lee Kip Lee

Aside from noting the cross-cultural features of the dress, it is worth mentioning the hybridity of the young woman’s accessories. In her right hand, she holds a closed white feather fan on which a floral design is vaguely visible. Ostrich feather fans were among the most popular accessories of the age in the West, and holding a closed fan gave the impression that the holder was a decent wife and/or mother rather than a flirtatious coquette who used her fan to draw men’s attention.15

Jewellery had a very significant role in the lives of nyonyas who wore extravagant anklets, bangles, belts, bracelets, brooches, earrings, hair pins, lockets, pendants, and rings to demonstrate their socio-economic background.16 Nyonyas wore bangles and bracelets (gelang tangan) always in pairs. Considering this, it is possible to observe that the young woman in the photograph is adorned with traditional jewellery. She has a pair of bracelets on her arms and unembellished diamond ear studs. Her hair is tied up in a bun (sanggul), yet her hair pin (cucuk sanggul) is not visible.

One of the most distinctive feature of Peranakan dress was the wearing of beaded or embroidered slippers (known as kasut manek or kasut sulam). The nyonya in the image integrates her Western dress with these slippers distinctive to her culture, and hence does not simply emulate the coloniser’s way of life but also complements it with her own unique culture using meaningful and symbolic items.

Another studio photograph from the same period presents another nyonya wearing a Western-style lingerie dress (Fig. 2). Similar to the previous image, this young woman wears a pair of bracelets—more lavishly designed—and a pair of identical diamond rings on her right hand. Another typical Peranakan accessory is her eye-catching diamond necklace that covers the high-necked lace collar of her dress. However, the watch ribbon which she wears on a slide chain is representative of Victorian and Edwardian fashion. By mingling her culture’s characteristic jewels with a fashionable Western garb and accessory, this young Peranakan woman interprets global trends in her own unique way.

On back: “Souvenir”, Straits Settlements or Indonesia, 20th century.

Collection of the Peranakan Museum, Gift of Mr and Mrs Lee Kip Lee

Untitled, Semarang, Java, Indonesia, c. 1922 to 1950s.

Collection of the Peranakan Museum, Gift of Mr and Mrs Lee Kip Lee

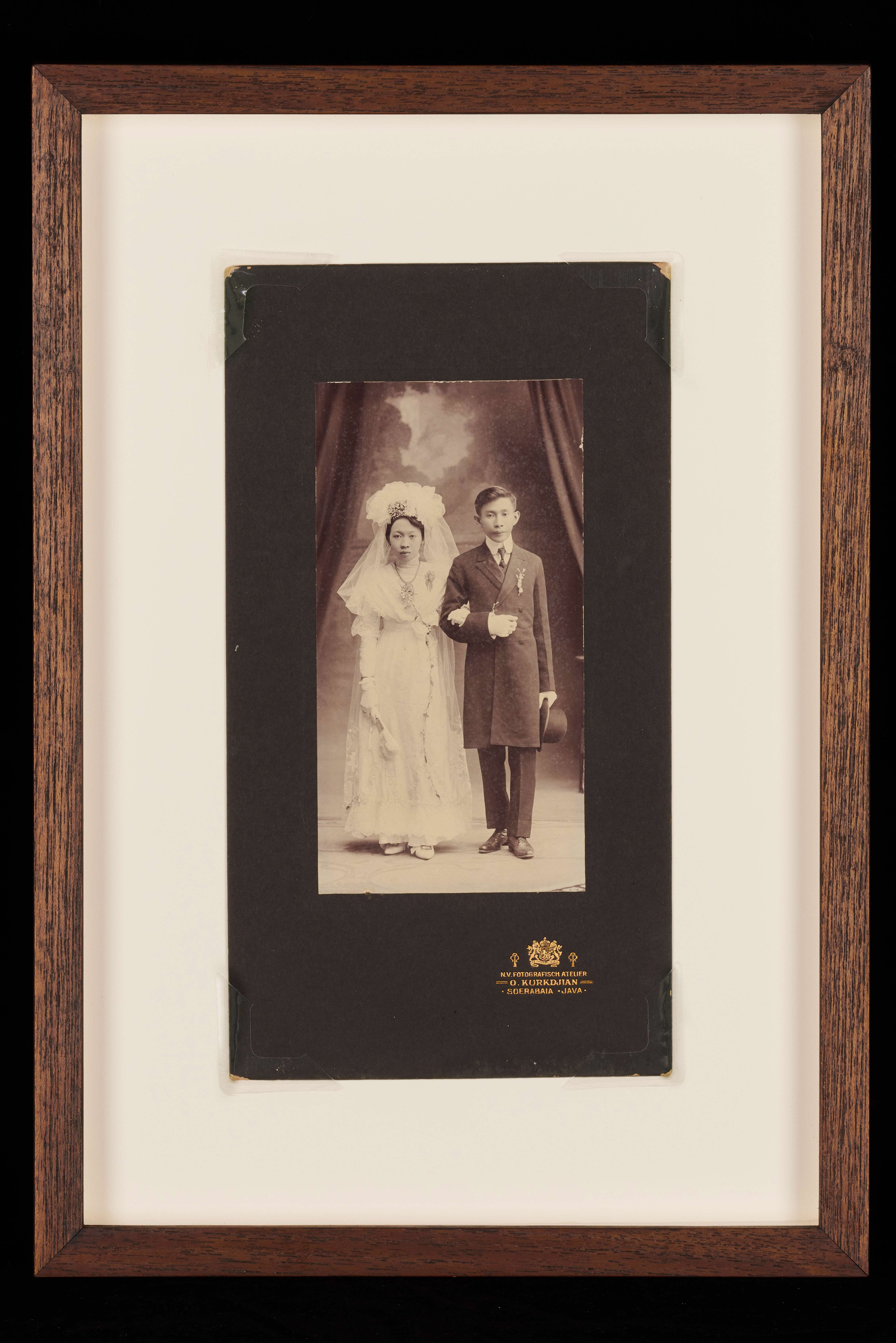

White became the colour of wedding dresses in the Western world in the 1830s, and Queen Victoria was the first bride who wore a veil during her wedding ceremony.17 White wedding gowns became also popular in Southeast Asia by the end of the 19th century. Many Peranakan women continued to wear their traditional two-pieced richly-embellished wedding costumes whereas many others preferred Western-style laces and veils. In this connection, Figure 4 displays a very striking example. The photograph of the Peranakan couple was taken at the famous Armenian photographer Ohannes Kurkdjian’s (1851-1903) studio in Surabaya which opened in 1890. The bride wore a high-necked transparent lace gown, white gloves and a veil. Her diamond pendant—which resembles a kerosang serong (paisley-shaped brooch also known as kerosang thoe)—and her brooch with a floral motif are worth mentioning. As a Javanese bride, her crown is decorated with melati flowers (Indian jasmine) and a string of melati buds flows from the centre of her gigantic pendant. She wears Western-style wedding shoes, and on her right hand holds a closed white ostrich feather fan onto which a delicate white tassel is attached.

Untitled, Surabaya, Indonesia, around 1920s.

Collection of the Peranakan Museum, Gift of Mr and Mrs Lee Kip Lee

In addition to dresses, lingerie blouses were also trendy global fashion items in the late 19th and early 20th centuries, and their influence on Peranakan women is traceable in black and white images. Another photograph taken in Kurkdjian’s studio in Surabaya (Figure 5) shows two young men in Western clothes—one in a military attire, the latter in suit and tie—on both sides of a woman who wears a two-piece lingerie costume. A wide satin belt combines the skirt and the blouse which has a semi-transparent high neck collar. The woman is sporting an Edwardian-style loose bun and fashionable white Oxford pumps. The most distinctive yet subtle Asian detail in the nyonya’s costume is the dark-coloured amulet on her blouse. It resembles the tiger claw talisman (kuku arimo tangkal) of the Peranakans which is believed “to protect the wearer from harm, especially against malevolent spirits, and to instil courage in the wearer”.18 Generally Peranakan children wore amulets in the early 20th Century when disease and mortality rates were soaring. Seeing an adult, especially a woman, openly wearing a tangkal was quite uncommon, and “meant that the wearer was a firm believer in the supernatural”.19

Untitled, Surabaya, Indonesia, ca. 1910s.

Collection of the Peranakan Museum, Gift of Mr and Mrs Lee Kip Lee round 1920s. Collection of the Peranakan Museum, Gift of Mr and Mrs Lee Kip Lee

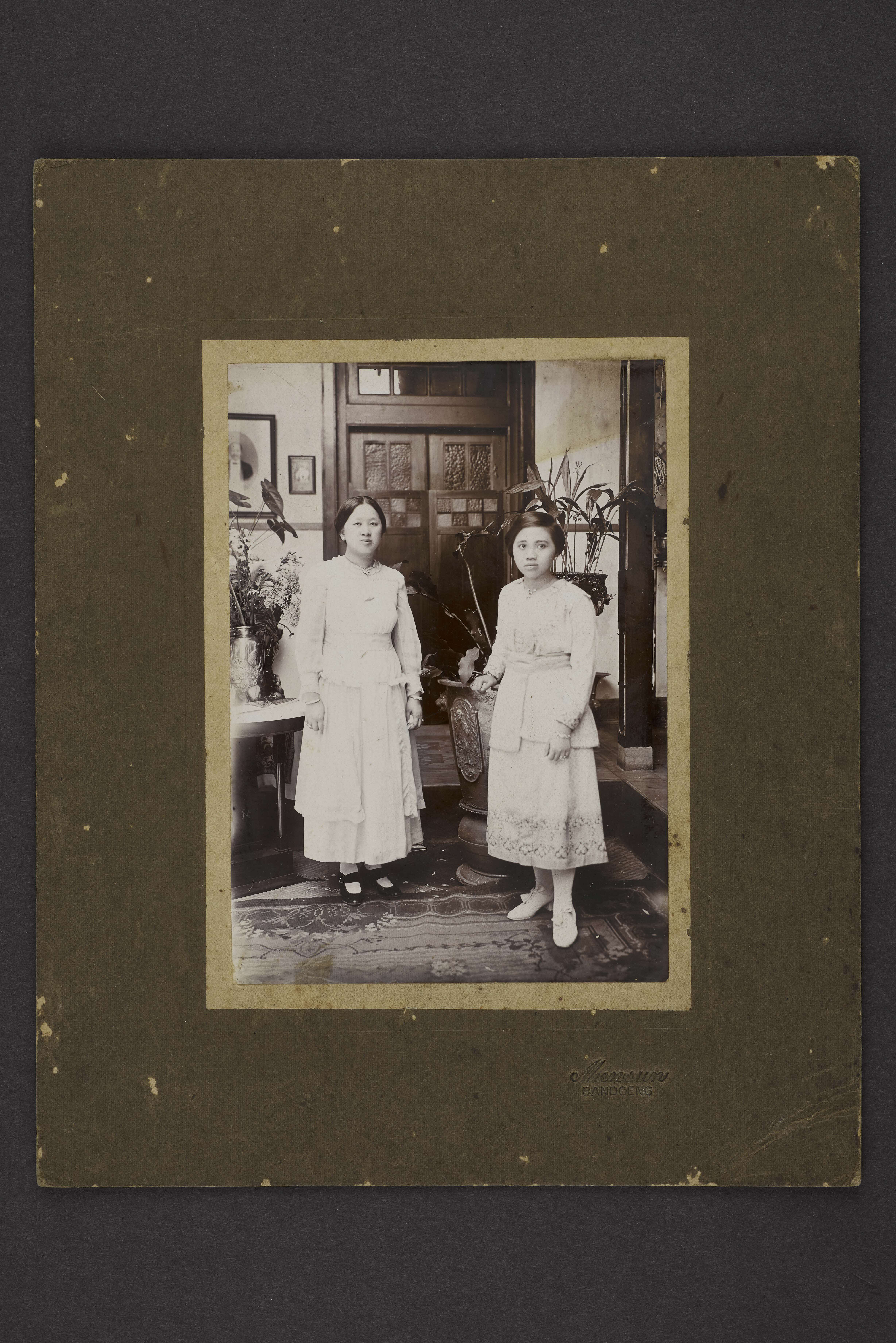

The photographs taken in the ensuing years demonstrate that the evolving white lingerie dress continued to be prevalent among nyonyas. Figure 6 shows two Peranakan women—presumably mother and daughter(-in-law)—posing in a domestic interior. Taken by the photographers of Mensun Bandoeng—a studio established both in the Dutch Indies and Straits Settlements around the 1860s—the image portrays the nyonyas standing in front of a dark wooden door, creating a striking contrast to their white Western gowns. Both women wear traditional Peranakan jewellery: diamond earrings, rings, necklaces, and twin bracelets. Two barely visible kerosangs are attached to the upper part of the elder lady’s rather plain dress. Since hemlines started to shorten during the first decade of the 20th century, hosiery that would be in harmony with dresses gained significance with “[t]he great vogue of short-skirted frocks”.20 In line with this trend, the two women in the photograph pose in white stockings that match their dresses and Western shoes, and hold white handkerchiefs in their hands. On the top left corner, there is a portrait photograph of a solemn ancestor wearing a black Western coat. The double cranes on the silver vase symbolise longevity.

Untitled, Bandung, Java, Indonesia, ca. 1920 to 1940.

Collection of the Peranakan Museum, Gift of Mr and Mrs Lee Kip Lee

Conclusion: Lingerie dress and self-expression

The lingerie dress, one of the most enduring popular fashion items in the modern Western world, prevailed in late 19th century and especially early 20th century Southeast Asia. Peranakan women, who adopted Europeanized sarong kebaya, concurrently created a Peranakan way of wearing the trendiest lingerie dresses. They did not merely mimic their Western counterparts but found the most impressive way of expressing themselves by combining a globally cherished attire with some of their traditional fashion pieces.

As Peter Lee emphasises, “[h]ybrid cultures like that of the Peranakans cannot be simplistically and neatly dissected into Chinese, Malay, and colonial segments; they are intrinsically unstable, varied, and multi-layered."21 The Peranakan community played a distinct role and displayed diverse cultural responses to different circumstances in Southeast Asian history. In this context, “[t]he story of Peranakan fashion is interesting because it does not fit any neat category”,22 and making generalizations about Peranakan fashion choices and trends would limit others’ understanding of this community, its interactions with other cultures, and the shaping and evolution of the Peranakan identity. In this context, the Peranakan way of wearing lingerie dresses in the early 20th century was not just a manifestation of colonial influence, but rather one of the authentic modes of clothing through which Peranakan women expressed their unique identities.

This research was supported by the National Heritage Board’s Heritage Research Grant.

Notes

- “Chinese Peranakans are the majority, but there are also Peranakan communities of other ethnicities in Southeast Asia, including Arab, Indian, and Eurasian.” Jackie Yoong, “Introduction” in Randall Ee, et. al., Peranakan Museum Guide. Revised edition. Singapore: Asian Civilisations Museum for the Peranakan Museum, 2013, p. 12.

- “Lauren Nitschke, “Marie Antoinette: History’s Controversial Fashion Queen”, The Collector, 14 December 2021, https://www.nst.com.my/news/nation/2019/12/546479/showcasing-peranakan-dress-style-world, accessed on 25 January 2024.

- “Alan Teh Leam Seng, “Showcasing Peranakan Dress Style to the World”, New Straits Times, 10 December 2019, https://www.thecollector.com/marie-antoinette-controversial-fashion-queen/, accessed on 21 March 2024.

- Sarah, Edwards, “‘Clad in Robes of Virgin White’: The Sexual Politics of the ‘Lingerie’ Dress in Novel and Film Versions of The Go-Between.” Adaptation, vol. 5, no. 1 (2011), p. 25.

- Ibid.

- “All Dressed in White: Antique Lingerie Dresses”, http://www.vintageconnection.net/LingerieDresses.htm, accessed on 21 March 2024.

- “Peter Lee. “Peranakan Fashion and its International Sources: Sarong Kebaya”, BeMuse, vol. 4, issue 2, April to June 2012, https://www.roots.gov.sg/stories-landing/stories/peranakan-fashion-and-its-international-sources/story, accessed on 28 March 2024.

- G. William Skinner, “Creolized Chinese Societies in Southeast Asia” in Anthony Reid,ed., Sojourners and Settlerzs: Histories of Southeast Asia and the Chinese, Honolulu: University of Hawaiʻi Press, 2001, p. 69.

- Amry Vandenbosch, “A Problem in Java: The Chinese in Dutch East Indies”, Pacific Affairs, vol. 3, no. 11 (1930), 1012.

- Thienny Lee, “Dress and Visual Identities of the Nyonyas in the British Straits Settlements; Mid-Nineteenth to Early-Twentieth Century”, PhD Thesis, University of Sydney, 2016, pp. 188-235.

- Courtney Fu, “Collecting and Curating Peranakan Fashion: An Interview with Peter Lee, Fashion Theory, vol. 24, no. 6 (2020), p. 965.

- Daniel Milford-Cottam, Edwardian Fashion. London: Shire Publications, 2014, p. 5 and 6.

- ““Artistic Gowns in Charming Fabrics. Latest Designs in Muslin”, The Straits Times, 28 August 1908, p. 10, https://eresources.nlb.gov.sg/newspapers/Digitised/Article/straitstimes19080828-1.2.103, accessed on 1 April 2024.

- Margaret Bocquet-Sieck, “The Peranakan Chinese Woman at a Crossroad” in Lenore Manderson, ed., Women’s Work and Women’s Roles: Economics and Everyday Life in Indonesia; Malaysia, and Singapore. Canberra and New York: The Australian National University, 1983, p. 50.

- Ariel Beaujot, Victorian Fashion Accessories, London & New York: Berg, 2012, p. 80.

- For detail, please see Lillian Tong, Straits Chinese Gold Jewellery: The Private Collection of Peter Soon, Penang: Pinang Peranakan Mansion Sdn Bhd, 2014.

- Michel Pastoureau, White. The History of a Colour, trans. by Jody Gladding, Princeton & Oxford: Princeton UP, 2023, p. 196, 200.

- Jennifer Ng, “The ‘Lost’ Peranakan Reimagined: Creating New Interpretation of Lost Peranakan Objects through Contemporary Artistic Imagination”, PhD thesis, Birmingham Institute of Creative Arts, 2023, p. 86.

- “Amulet (Tangkal)” in Randall Ee, et. al., Peranakan Museum Guide. Revised edition. Singapore: Asian Civilisations Museum for the Peranakan Museum, 2013, p. 206.

- Daniel Delis Hill, Necessaries: Two Hundred Years of Fashion Accessories, San Antonio, TX: Gemini Dragon, 2015, pp. 102-103.

- Peter Lee, “Peranakan Fashion and Identity: 1600-1950” in Randall Ee, et. al.., Peranakan Museum Guide. Revised edition. Singapore: Asian Civilisations Museum for the Peranakan Museum, 2013, p. 23.

- Fu, p. 966.