The Chinese pagoda's lineage can be traced back to the ancient Indian stupa, a dome-shaped monument built in homage to Buddha Shakyamuni. While stupas served as symbolic tombs and relic receptacles, Chinese pagodas evolved into multi-storied structures that could be entered and ascended. This architectural transformation was influenced by advancements in Chinese building technologies, resulting in a diverse array of pagoda styles.

The intricate designs and towering presence of Chinese pagodas captured the imagination of people far beyond China’s borders. Their evolution from simple stupas to complex multi-storied structures reflects a dynamic interplay between religious devotion, architectural ingenuity, and cultural expression. Western fascination with Chinese pagodas began in the 17th century when European explorers and traders brought back stories and sketches of these exotic structures. They were seen as symbols of the mysterious and ancient culture of China, sparking curiosity and admiration. This fascination was further fueled by the trend of Chinoiserie in the 18th century, a European interpretation of Chinese and East Asian artistic traditions. Pagodas became popular motifs in European gardens, architecture, and decorative arts.

In 1915, at the Panama-Pacific International Exposition in San Francisco, visitors were captivated by a stunning display in the Chinese Section of the Education Palace. Here, 84 intricately carved wooden models of pagodas stood as 1:50 scale replicas of some of China’s most iconic structures. These models, ranging from 30 cm to 2 meters, represented different regions and historical styles, showcasing the grandeur of Chinese architectural heritage in a comprehensive manner.

This showcasing of 84 pagoda models marked a crucial moment of East-West exchange. For the first time, the Western world was given a comprehensive glimpse into the grandeur of Chinese architecture, drawing from diverse styles, regions, and eras. However, the story behind these models remained largely untold—until now. The Asian Civilisations Museum’s latest exhibition, Pagoda Odyssey 1915: from Shanghai to San Francisco, invites visitors to rediscover these exquisite models and the fascinating history behind them.

2023-00336

Inner Mongolia, Chifeng

Liao dynasty, 1098

2023-00393

Jiangsu province, Suzhou

Southern Song dynasty, 1153

The Tushanwan Orphanage: A Beacon of Artistry

The remarkable models showcased at the 1915 exposition were crafted by over 300 orphaned artisans at the Tushanwan Orphanage in Shanghai. Founded in 1864 by Jesuits in the Xujiahui district, Tushanwan was more than just a refuge for children orphaned by natural calamities and social upheaval. It was a hub of creativity and innovation, where vocational training in arts and crafts equipped orphans with valuable skills.

Realizing that food, shelter, and standard education were not enough, the Jesuits set up multiple workshops to teach the orphans various crafts, supervised by professionally trained Jesuit priests. These workshops included painting, woodcarving, photography, metalwork, shoemaking, and more. Among these, the woodcarving workshop became the most important, gaining international renown for its exceptional craftsmanship.

The carpentry and sculpture workshop was originally established in Caijiawan Orphanage, another Jesuit orphanage in Shanghai, and integrated into Tushanwan in 1864. Initially producing objects for religious use, such as altarpieces and devotional sculptures, by the mid-1910s, the workshop began creating secular items, particularly Western-style furniture with Chinese motifs. Under the supervision of Father Aloysius Beck (1854–1931), the workshop achieved success at various international expositions. German-born and educated in Paris, Beck had a deep appreciation for Chinese culture. He oversaw several important international commissions, including components for King Leopold II’s Chinese Pavilion in Brussels. One of Beck’s particular fascinations was the Chinese pagoda, and under his leadership, the workshop began producing pagodas as souvenirs. These pagodas, modeled after actual structures, must have been quite popular, reflecting both Beck’s interest in Chinese culture and catering to the Western fascination with these structures. The pagoda models demonstrated meticulous craftsmanship in woodcarving, with some vividly painted to accentuate their designs and authenticity, while others remained unpainted, showcasing the natural beauty of wood texture.

The Making of Pagoda Models

Eventually, this success attracted a commission to create a collection of iconic pagodas from across China. Around 1910, the Carpentry and Sculpture Workshop at Tushanwan received a unique commission to craft models of pagodas from different regions of China. While the details of this commission remain largely unknown, it was likely intended as a study collection for a museum or university.

This project presented significant challenges. Beck had already spent considerable time researching pagodas, but conducting direct surveys across China proved impractical for him and the workshop’s artists. They relied heavily on written descriptions and photographs, as well as information gathered by the Jesuits, who had been active in China for centuries. Despite the challenges, the Tushanwan artists were ambitious and aimed to present the geographical diversity and stylistic differences among Chinese pagodas. They selected forms that were unique to specific regions and those built with unusual materials or distinctive types, as well as representatives that cover every significant historical period from the Tang dynasty onwards.

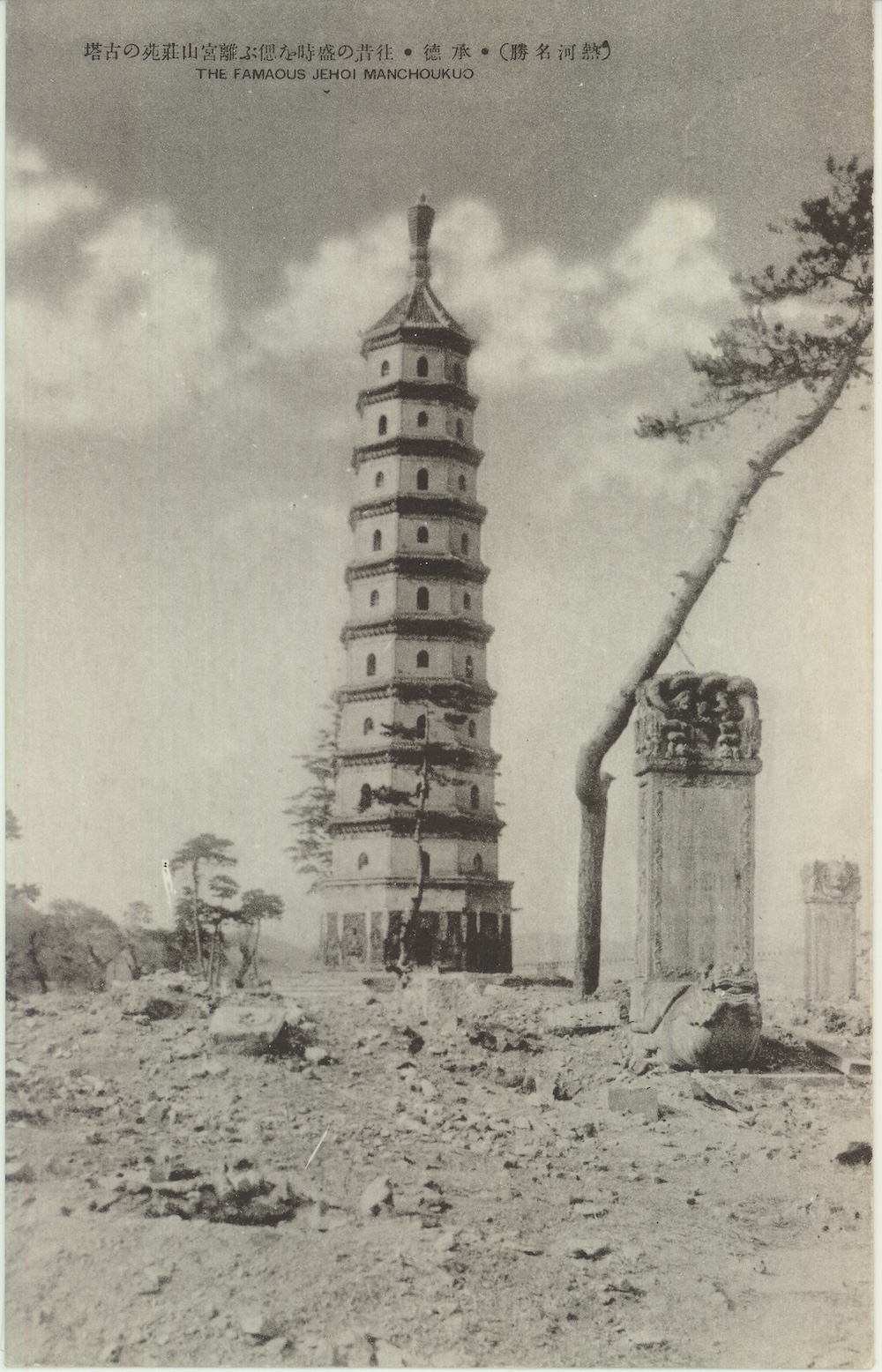

2023-00335

Hebei province, Chengde

Qing dynasty, 1754-64

International Center for Chinese Studies, Aichi University.

2023-00358

Shaanxi province, Xianyang

Ming Dynasty, 1605-1610

Unfortunately, as the 84 pagodas were nearing completion, the workshop received the disappointing news that the commission was canceled. Undeterred, Beck decided to complete the project as originally planned. He secured a spot for the pagodas at the 1915 Panama Pacific International Exposition by contacting the American Consulate in Shanghai, hoping to find a buyer—possibly a museum or university in the US. Beck enlisted Father Dennis John Kavanagh, a fellow Jesuit in San Francisco, to assist with the exhibition and sale. To prepare the pagodas for the long journey across the Pacific, the pagodas, a large wooden archway, and other objects weighing over 150tonneswere disassembled and packed by the workshop, probably using newspapers. Three orphans from the workshop accompanied the shipment to assist with installation and perform necessary repairs on arrival.

The Presentation of the Pagodas in the Panama Pacific International Exposition

The Panama-Pacific International Exposition was a monumental world's fair that celebrated both the completion of the Panama Canal in August 1914 and San Francisco’s recovery from the 1906 earthquake. Thirty-one countries participated, with twenty-three constructing pavilions to showcase their cultural and technological advancements. The exposition introduced many pioneering technologies on the world stage. It featured demonstrations of the first transcontinental phone call and a fully operational automobile assembly plant. It also pioneered the use of indirect outdoor lighting and was the first exposition to extensively use movies for promotional purposes. As the Tushanwan workshop was a vocational school, they were assigned to the China section of the Palace of Education within the exposition. Thanks to the work of Father Kavanagh and ten football players from St. Ignatius’ College (where Father Kavanagh taught), the pagodas and other exhibits, such as the gateway, were assembled and ready in the Education Palace. However, Brother Kavanagh was not interested nor familiar with Chinese architecture, and from old photos we know the pagodas in the exposition were randomly and chaotically put together.

San Francisco History Center, San Francisco Public Library.

The Pagodas at ACM

To preserve the original research intent behind these models, the current exhibition has taken a deliberate approach to arrange the pagodas both chronologically and thematically. This thoughtful organization aims to enhance visitors' comprehension of the Chinese pagoda's evolution, providing a structured journey through time that highlights the architectural, cultural, and regional developments of these iconic structures. The exhibition is organized to trace the evolution of pagodas, highlighting key regional and stylistic differences. Tang dynasty pagodas, with their square floorplans and simplicity, contrast with the octagonal, pavilion-style pagodas of the Song dynasty, designed for sightseeing. The dense-eaved pagodas of the North differ from the slender, airy pagodas of southern China. The Ming and Qing dynasties perfected previous styles and introduced "literary peak towers" built according to feng shui principles. A key highlight is the "Lost Pagoda" which showcases the Tushanwan Workshop's efforts to preserve the memory of pagodas lost to natural disasters, war, and social upheaval, capturing their essence and historical significance.

2023-00357

Shaanxi province, Xi’an

Tang Dynasty, 652-54

2023-00337

Hebei province, Dingzhou

Northern Song dynasty, 1001-55

Coda: The Legacy of the Tushanwan Pagodas

After the exposition ended, the full set of pagodas and a large wooden archway were acquired by the Field Museum of Natural History in Chicago. The Tushanwan project was the first attempt at systematically researching, documenting, and reproducing Chinese pagodas. This effort preceded academic interest by several decades, and it was only in the 1930s that architectural historians such as Liang Sicheng and Lin Huiyin began to seriously study these structures. Notably, the models played an important role in "Pagoden" (1931), the first systematic study of Chinese pagodas by the German sinologist Ernst Boerschmann. Boerschmann relied on the models for pagodas he had not personally examined, and even used them as illustrations in the book. The pagodas were mostly kept in storage over the course of the 20th century, passing from the Field Museum into private hands, and eventually to the Asian Civilisations Museum. Had they been unsold and returned to Shanghai, they might have been separated and lost after the orphanage closed in 1960. Their careful preservation allows us to appreciate the important role they played in the study of Chinese architecture, as well as the creativity and craftsmanship that went into making them.

"Pagoda Odyssey": at the Asian Civilisations Museum brings these remarkable models and their stories back to public attention, offering a unique glimpse into the artistry and cultural exchange that shaped them. Visitors are invited to explore the journey of these pagodas from their conception in Shanghai to their historical showcase in San Francisco, celebrating a century-old tale of craftsmanship and cultural dialogue. The exhibition not only highlights the meticulous craftsmanship of the Tushanwan artisans but also reflects the broader historical context of Sino-Western interactions and the enduring allure of Chinese architectural aesthetics.

Pagoda of Repaying Kindness大报恩寺琉璃塔

On loan from the Field Museum of Natural History, Chicago, 130439

Jiangsu province, Nanjing

Ming dynasty, 1412-28