Maghain Aboth Synagogue, whose name means “Shield of our Fathers” in Hebrew, was officially consecrated on 4 April 1878. It is the oldest surviving synagogue in Southeast Asia and was gazetted as a National Monument in 1998.

The term “synagogue” comes from the Greek word synagein (“to bring together”). The synagogue can take any architectural building form and can be located at any location as long as there are ten Jewish men above the age of 13, constituting the minyam (“quorum” in Hebrew), gathered for prayer. Hence, it is this quorum of ten men rather than the building itself that constitutes the synagogue in its most fundamental sense.

Maghain Aboth Synagogue is not the first synagogue set up by the Jews in Singapore. Baghdadi Jews, who arrived in Singapore from Calcutta in 1819 in search for new business opportunities, established the first synagogue in a shophouse at the Boat Quay area where they had chosen to settle down. The street where the first synagogue was located is still called Synagogue Street today.

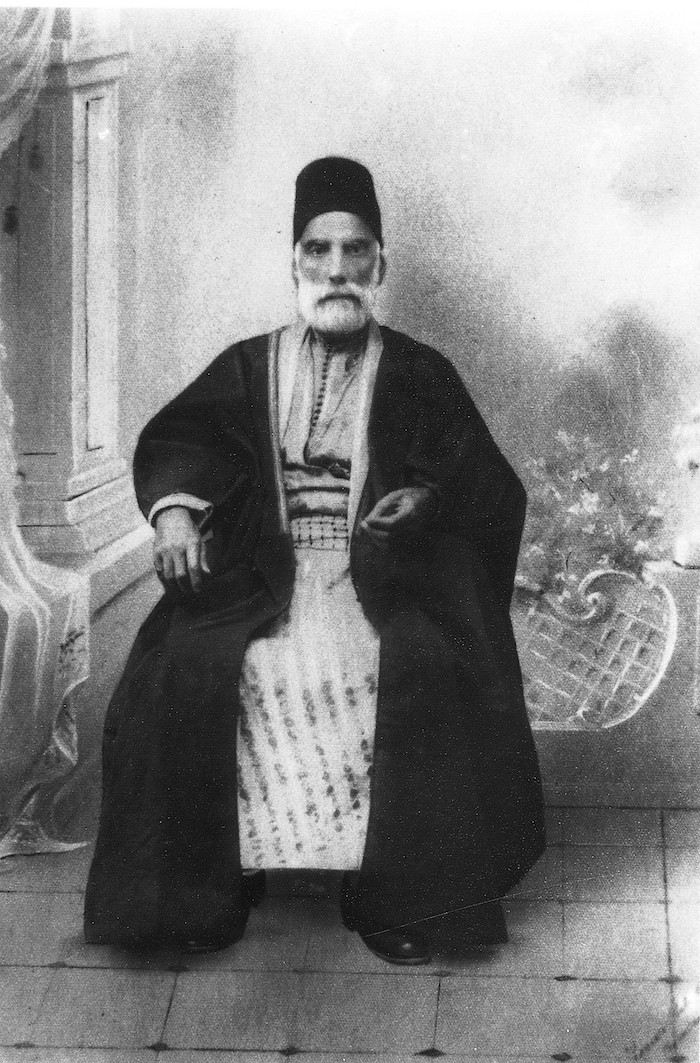

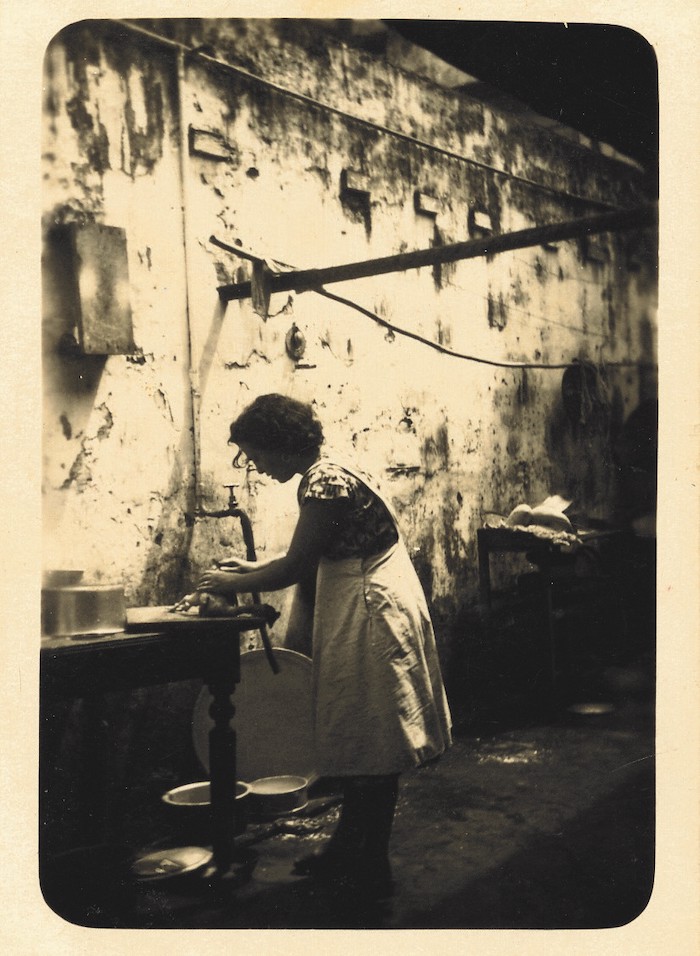

Portraits of Singapore’s first Chief Minister David Marshall’s grandparents from Iraq (date unknown). The early Jewish community would wear Middle Eastern robes and rhappah (dresses) such as these in the above photographs. Photo credit: Estate of Joan Marshall.

By the 1870s, the wealthier Jews moved away from Boat Quay and the poorer new immigrants congregated in the Middle Road area instead. As a result, the old “shophouse” synagogue at Boat Quay was under-used and increasingly dilapidated. The community eventually decided to sell the old synagogue at Boat Quay and built a new synagogue on Waterloo Street, where Maghain Aboth Synagogue still stands today.

This plot of land was likely chosen because it was within walking distance of the mahallah (Arabic for “neighbourhood”), where the deeply religious, poorer Jews lived. The mahallah in Singapore had no formal boundaries, but was concentrated around Middle Road, Selegie Road, Sophia Road, the Government House estate (around the Istana), Bras Brasah Road, Rochor Road, and Victoria Street. The synagogue had to be close to their homes because Orthodox Jews do not ride on the Sabbath and holidays.

Jewish woman preparing chicken for the Shabbat dinner in the mahallah (1930s). Photo credit: Elias Meyer Elias.

Ellison Building at the junction of Selegie Road and Bukit Timah Road (1980s-1990s). The building was built by Issac Ellison, a prominent member of the local Jewish community, in 1924. G P Reichelt Collection, courtesy of National Archives of Singapore.

David Elias Building at the junction of Middle Road and Selegie Road (1986). Built in 1928 by Jewish businessman David Elias, the building features a few Stars of David on its façade. Courtesy of National Archives of Singapore.

Maghain Aboth Synagogue was originally a one-story building with a tall, covered carriage entrance. The exterior of the main building was constructed of brick and mortar with cream-coloured stucco, in the Neoclassical style of the colonial period. Like all synagogues in the East, the entrance face west toward Jerusalem.

Entrance of Maghain Aboth Synagogue. The wide covered porch was built for horse carriages to pass through (2013). Courtesy of Preservation of Sites and Monuments (PSM).

Six-pointed Star of David (or Maghain David – “shield of David”) distinguishes it as a Jewish building. There are three of them on the façade of Maghain Aboth Synagogue (2013). Courtesy of Preservation of Sites and Monuments (PSM).

The upper gallery is reserved for women. Before air-conditioning was installed, the high ceiling and large windows allowed the interior to be well ventilated. (2013). Courtesy of Preservation of Sites and Monuments (PSM).

October 7th commemoration (2024). Courtesy of Jewish Welfare Board

In 1893, a women’s section and a simple wooden gallery were constructed on the second level. A more solid and permanent gallery replaced the wooden gallery in 1925, and is still in use today. Men and women are segregated during the prayer service. The separation of the sexes is believed to enable focused meditation and eliminates distraction.

Cabinets in front of the seats are used during the part of the prayers that requires standing (2013). Courtesy of Preservation of Sites and Monuments (PSM).

Inside Maghain Aboth Synagogue, the walls are devoid of decorations, images or pictures of any kind. The seats are framed in wood with cane backings to allow air circulation in the hot tropical weather.

Prayer Session in Maghain Aboth during Sukott (also known as the Feast of the Tabernacles). The bimah stands on a raised platform in the middle of the sanctuary (2024). Courtesy of Jewish Welfare Board

The bimah (or pulpit) stands in the middle of the sanctuary and faces the ahel (or ark). It is on a raised platform with timber railings and steps. It is from the bimah that the officiant reads the Torah scrolls. The Torah is read in rotation at the bimah every Sabbath. In Orthodox congregations, only male members of the community can read the Torah and are never touched with the fingers while reading but a special pointer is used instead.

The ahel (or ark) of Maghain Aboth Synagogue (2013). Courtesy of Preservation of Sites and Monuments (PSM).

The sacred Torah scrolls are kept inside the ahel, stored in traditional Iraqi conical scroll cases made of silver and velvet (2013). Courtesy of Preservation of Sites and Monuments (PSM).

In Maghain Aboth Synagogue, the ahel is a dome-shape niche that is recessed into the farthest wall facing the main entrance. When one is facing the ahel, one is symbolically facing the holy city of Jerusalem where the Holy Temple once stood. As such, it is the most sacred place in a synagogue and the focal point of prayer. All congregants stand when the ahel is opened.

The ahel (ark) covered with three embroidered curtains (2013). Courtesy of Preservation of Sites and Monuments (PSM).

Singapore’s First Chief Minister David Marshall making a speech in front of the ahel (ark) at the 100th anniversary of Maghain Aboth (1978). Ronni Pinsler Collection, courtesy of National Archives of Singapore.

The ahel is usually covered by the parochet (or fringed curtain), symbolic of the original curtain that protected the Ark in ancient Israel’s Holy Temple. The three curtains at Maghain Aboth Synagogue are embroidered with Hebrew verses, and symbols central to the Jewish beliefs. During High Holy Days such as Rosh Hashanah (Jewish New Year) and Yom Kippur (Day of Atonement), the dark curtains in front of the Ark are replaced with white ones symbolising purity, forgiveness and a clean slate.

Behind the curtains, the eternal lamp that is always lit is hung in the Ark. It is a symbol of the Western Lamp, the light burning perpetually in Jerusalem’s Holy Temple and represents God’s eternal presence and protection.

During the Second World War, around half the Jewish population fled Singapore before the Japanese invasion in 1942. A small number of Jews were also interned with the Europeans as they were part of the Volunteer Corps. During these difficult times, Maghain Aboth Synagogue served as a sanctuary for the Jewish community—where they can meet and comfort one another, as well as raise money to support the poor in the community. The Japanese also allowed regular services at the synagogue to continue.

Jews baking matzoth (flatbread) at Maghain Aboth Synagogue for all the internees at Changi Camp to be eaten for the Passover meal (c.1942-1944). Photo credit: Jewish Welfare Board.

Maghain Aboth Synagogue, which was used to store ammunition and pig iron during the war, was fortunately left relatively unscathed during the war. Most of its cane benches had gone missing but the Japanese did not touch their precious Torah scrolls. After the war, poor Jews with no place to live also took up residence on the synagogue grounds.

Singapore’s first Chief Minister David Marshall unveiling the large menorah (Jewish candelabra) and plaque to commemorate the 100th anniversary of Maghain Aboth Synagogue (1978). Photo credit: Jewish Welfare Board.

In 1945, the Jewish population in Singapore has dropped from nearly 2,000 before the war to an estimated 700. Many middle-class families who had fled during the war to places like Australia, Palestine, England and the United States never returned. Other evacuees trickled back into Singapore only to leave again after a few years. The local Jewish population steadily declined for the next few decades. Today there are around 2,500 Jewish residents in Singapore, majority of whom are expatriates from Israel, America, Australia and Europe.

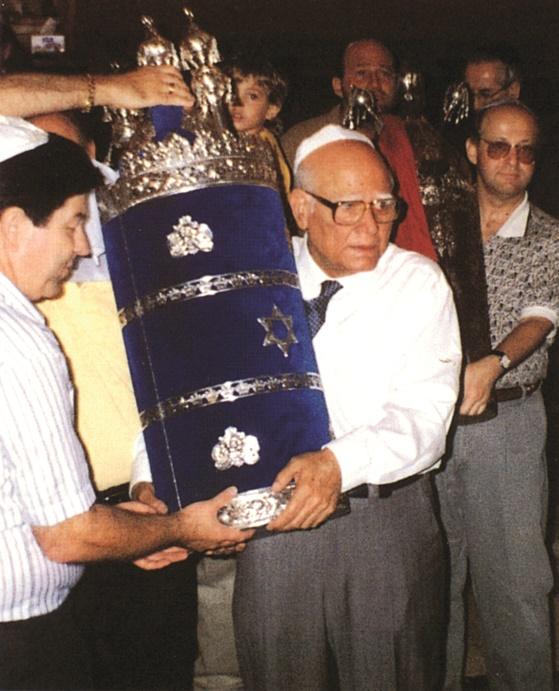

Jacob Ballas (middle) donated a Torah in memory of his mother (1997). Photo credit: Jewish Welfare Board.

Jacob Ballas Centre on the grounds of Maghain Aboth Synagogue (2023). Photo by author.

In 2007, Jacob Ballas Centre – named after the well-known Jewish stockbroker and philanthropist – was opened next to Maghain Aboth Synagogue. This provided additional facilities for the Jewish community, including a slaughtering room for chickens, a kosher shop, and a social hall.

Prayer session outside Maghain Aboth Synagogue during Sukkot (Feast of the Tabernacles) (2024). Courtesy of Jewish Welfare Board.

Marching and dancing with the Toral scrolls around the bilmah on Simchat Torah (“Joy of the Torah”), celebrating the completion of the annual reading of the Torah (2024). Courtesy of Jewish Welfare Board.

Presently managed by the Jewish Welfare Board, Maghain Aboth Synagogue remains the main place of worship for the Jewish community. In addition to daily prayer and Sabbath services, festive celebrations and commemorative events are still regularly held in the synagogue.

3D Model of Maghain Aboth