TL;DR

The prewar Japanese community in Singapore is often associated with karayuki-san (sex workers), spies, and the area around Middle Road. But this was, in fact, a complexly divided community whose impact could be felt far beyond any one neighbourhood. By mapping the Japanese presence in colonial Singapore, we can come to a greater understanding of its growth and its decline.

There were never more than a few thousand Japanese residents in prewar Singapore, but this small community played an outsize role in the colonial port city. As allies and eventual enemies of the British, as shopkeepers, photographers, and dentists serving all communities, and as one of the most prominent groups involved in the sex trade, Japanese residents were firmly embedded in urban life.

They played this role in part because much of the community lived and worked around the centrally located Middle Road neighbourhood. By charting the paths of Japanese residents and institutions in and beyond Middle Road, we might come to a better understanding of how communities lived in colonial Singapore.

The Roots of Japanese Singapore

The first recorded Japanese resident of Singapore was Yamamoto Otokichi, a shipwrecked sailor who washed up on the shores of North America at a time when Japanese law still forbade overseas travel. Unable to return to Japan, Otokichi settled in Singapore in the mid-nineteenth century. After the Meiji Restoration of 1868, a steady stream of Japanese expatriates began settling in Singapore. The port’s central role in international passenger shipping before the Second World War made it hub for Japanese travelers and entrepreneurs who were eager to explore a rapidly modernizing world.

The most impactful early group of Japanese settlers in Singapore were prostitutes, who were known as karayuki-san and generally came from the island of Kyūshū. Colonial Singapore was the site of a sprawling sex industry and, while some Japanese women came of their own volition, others were trafficked here by a network of Japanese and non-Japanese pimps.

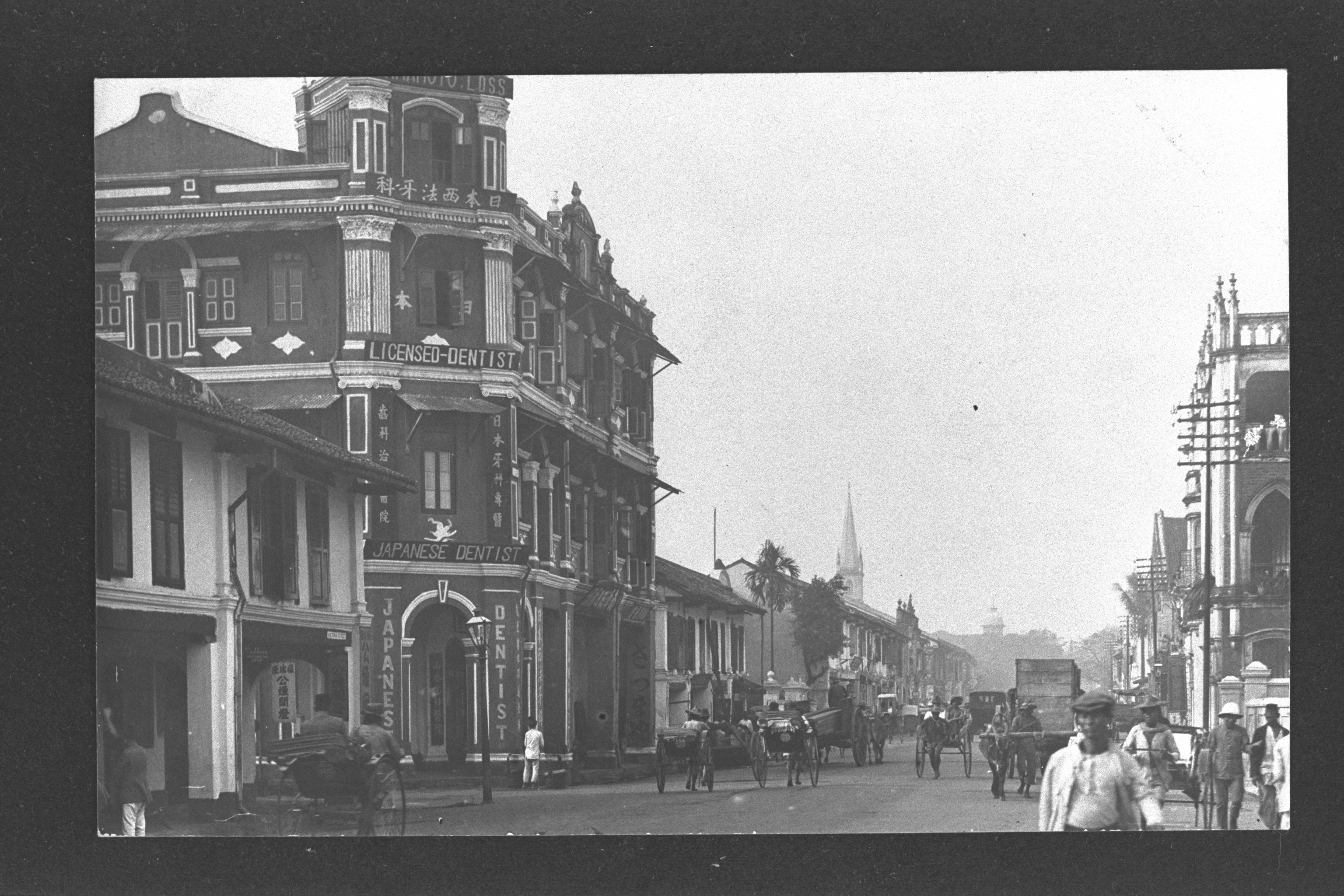

Most lived in brothels concentrated around Malay Street, Hylam Street, and Malabar Street (present-day Bugis Junction), which the Japanese came to refer to collectively as “Suteretsu” (a transliteration of the English word ‘Street’). These karayuki-san became the nucleus of a new community in Singapore: Japanese merchants and professionals set up shop nearby to cater to their needs and by the turn of the twentieth century a full-blown Little Japan had developed along Middle Road and the surrounding streets.

Malay Street in the Suteretsu red-light district. Numerous Japanese signboards are visible. 1910s. Courtesy of National Archives of Singapore.

At the time, Singapore was one of the first stops for the vast majority of Japanese travelers on their way to India, the Middle East, and Europe. These travelers, who included some of Japan’s most prominent political leaders, artists, authors, and athletes, often stayed in the Japanese hotels that operated around the intersection of Beach and Middle Roads. Over the course of the Anglo-Japanese alliance (1902–1923), Japanese sailors were also a regular presence in the area. This stream of visitors injected a sense of excitement and energy into the growing Japanese resident community along Middle Road.

The Miyako Hotel (left) on Beach Road, c. 1920. Courtesy of National Archives of Singapore.

And yet, concentrated around the brothels of Suteretsu as it was, the neighborhood also developed a rough reputation. Members of Japanese high society on their first stop of a world tour brushed shoulders with brash entertainers, fastidious shopkeepers, gregarious restaurateurs, and gangsters. The neighborhood exposed visitors to a cross-section of Japanese society, one that was at times uncomfortably hardscrabble for upper-class Japanese.

A Community Transformed

The First World War brought unprecedented changes to Japan’s relationship with Southeast Asia. As the economies of Europe turned away from their Asian colonies and focused on devastating their own continent, Japanese firms moved swiftly to take advantage of new opportunities in Southeast Asia. Japanese conglomerates firmly established themselves in what we now call the Central Business District (CBD) but what they then referred to as “Gudan” (from gudang/godown).

Branch office of Nippon Yūsen Kaisha (NYK) at 16 Raffles Place (left). 1930. Collection of the National Museum of Singapore.

As a result, the 1910s brought a new wave of Japanese expatriates to Singapore, taking up jobs around Gudan and settling into comfortable bungalows alongside Western businessmen. Highly educated and class-conscious, these new arrivals were not happy with the effect that the rough-and-tumble residents of Middle Road had on their empire’s reputation. The Japanese community used the geographic divisions of Tokyo to describe a growing split among its residents: Middle Road was associated with the lower-class districts of Shitamachi, and the Gudan crowd with the genteel neighbourhoods of Yamanote. The Shitamachi/Yamanote split was one of wealth, education, and manners, and Singapore’s budding Japanese-language newspaper industry spoke ominously of tensions between the two, and particularly between young men.

In the 1910s and 1920s, a handful of leaders in the community worked to ease these tensions. In 1915, the Japanese consulate sponsored the creation of a Japanese Association, whose first leaders were a naval surgeon general, Suzuki Shigemichi, and a prominent businessman, Nakagawa Kikuzō. Nakagawa organized educational speeches and activities for an associated Singapore Youth Association (Shingapōru Seinenkai), which served as a precursor for a full-blown Japanese Club, formed in 1922. The Japanese Club and Japanese Association moved into a shared clubhouse on Selegie Road in 1926.

Clubhouse of the Japanese Association and Japanese Club at 107 Selegie Road, c.1930s. The Japanese Association Singapore Collection, courtesy of National Archives of Singapore.

These organizations were meant to “encourage friendly feelings” among their members, which serves as some evidence that there were unfriendly feelings that needed to be addressed in the first place. But as Japanese historian Yano Tōru has argued, these organizations were generally dominated by the elite expats who began arriving in the 1910s, with the support of the consulate, and served to enforce their own values and priorities on the internally diverse Japanese resident population.

The culmination of this movement was the erasure of the first nucleus of the Japanese community: Suteretsu. In the late 1910s and early 1920s, a group of Japanese diplomats, businessmen, and religious leaders worked to shut down the Japanese brothel district. Roughly half of karayuki-san were repatriated, while the remainder found other work in Singapore. The closure of these brothels did mitigate some of the exploitation these women had faced, but it did not necessarily end it: underground Japanese prostitution would continue for years to come. But for many of the men involved in this movement, it had achieved its goal of removing a public stain on the Japanese Empire’s reputation in Singapore.

Turning Inward

In the 1910s and 1920s, the Japanese community in Singapore consolidated around a few key institutions that allowed a few elite leaders to promote their own ideals of what a Japanese person should be. This mirrors the experience of Europeans and Americans in Southeast Asia during this same period. As American historian Ann Laura Stoler has shown us, social clubs and associations were among the tools that Westerners in these colonies used to police the behavior of their rowdier, lower-class compatriots. And while the Japanese in Singapore seem to have been less obsessed with preventing mixed-race relations than their white counterparts, they seem to have been just as eager to ease the tensions within their communities by promoting nationalism.

A meal at the Japanese restaurant Tamagawa at 39 Hylam Street, c. 1930s. The Japanese Association of Singapore Collection, courtesy of National Archives of Singapore.

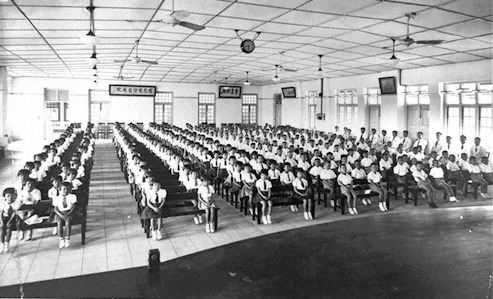

Students in the Japanese Elementary School, 115 Waterloo Street, currently the Stamford Arts Centre. 1927. The Japanese Association of Singapore Collection, courtesy of National Archives of Singapore.

In the late 1930s, there appears to have been an uptick in nationalist activities promoted by institutions like the Japanese Association and Japanese Club. While these organizations had long promoted traditional Japanese arts, this decade saw a greater emphasis on celebrating Japanese national holidays, culminating in series of ceremonies held in the 2600th year of the Japanese imperial calendar (1940). Nationalism may have helped ease the divisions within the Japanese community, but it also served to separate them from their neighbours in Singapore at a time when their empire grew increasingly isolated on the world stage. Tensions grew with the Chinese and eventually the British, and the Japanese Club was itself trashed by a group of Chinese men in 1935. In the face of these changes, many Japanese residents left Singapore in the years before the Second World War.

Sports meet commemorating the 2600th year since the mythical founding of the Japanese imperial dynasty. 1940. The Japanese Association Singapore Collection, courtesy of National Archives of Singapore.

On the Trail of the Japanese Consulate

One way to track the growth, transformation, and eventual isolation of the Japanese community in prewar Singapore is through the history of the Japanese Consulate (which was designated a Consulate-General in 1919). As with the community as a whole, the consulate got off to an uneasy start. In 1879, Hu Shi Ze was designated as Japan’s first Honorary Vice Consul in Singapore, but this early mission ended when he died the next year. In was only in 1889 that Japan established a permanent Consulate on Sophia Road, with Nakagawa Tsunejirō as its first Acting Consul.

The Consulate would remain on Sophia Road for the next twenty-four years. This put it in close proximity to the Japanese resident community along Middle Road, though its location at the foot of Mount Emily was perhaps a bit less hectic than the concentration of shops, brothels, and hotels closer to the sea. And as the Japanese community was transformed by the influx of Japanese firms and expats during the First World War, so too was the consulate.

While the Consulate worked with the Gudan-based expats to set up new communal institutions like the Japanese Association, it also relocated to the Gudan itself. After a brief stint on Cavenagh Road, the consulate moved into Raffles Chambers (which had recently been built by Swan & Maclaren) along Raffles Place in 1917. Here it was close to the headquarters of the Japanese conglomerates and shipping firms that began establishing themselves in the commercial heart of Singapore over the previous decade.

But the move was also emblematic of Japan’s rise in global politics. As a victorious power in the First World War and a close ally of the United Kingdom since the signing of the Anglo-Japanese Alliance of 1902, Japan attended the Paris Peace Conference of 1919 as the fifth great power of the world. This same year, its consulate in Singapore was upgraded to a Consulate-General, and in 1925 it moved into the newly built Union Building on Collyer Quay. As a great power with deep economic ties to Singapore, it might only have seemed natural for the Japanese to have their consulate-general in such a prominent location.

The consulate-general remained in the Gudan area for twenty-two years. But in 1939, it returned to almost exactly where it had begun in 1889. The consulate-general had bought Osborne House at the top of Mount Emily, an airy villa with a commanding view down Middle Road, from a Japanese dentist. It was from here that visitors in the 1930s would describe the sight of Japanese flags flying from the top of Mount Emily all the way down Middle Road to the sea during Japanese holidays.

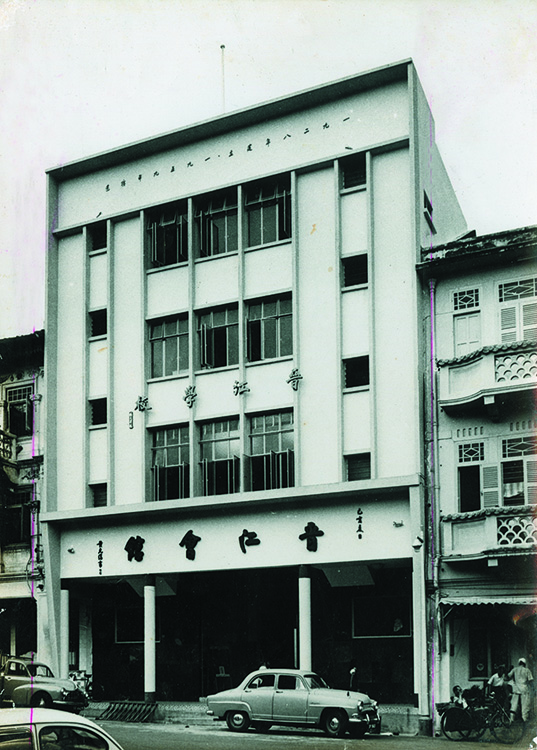

The Consulate-General of Japan, 11 Upper Wilkie Road. This postwar photograph was taken when it was a Girls Home run by the Social Welfare Department of the Ministry of Social Affairs. 1959. Ministry of Information and the Arts Collection, courtesy of National Archives of Singapore.

In many ways it might seem like the consulate-general had simply moved back to the traditional centre of the Japanese community in Singapore. Viewed from the outside, however, the move could have also symbolized the radical changes in Japan’s status as a great power in the 1930s. A Japanese army had taken over northeast China in 1931 and established a puppet state there in 1932. When this move was denounced by the international community, Japan withdrew from the League of Nations in 1933 following a fiery “sayonara” speech by Matsuoka Yōsuke to the league’s assembly. In 1936, Japan had signed an anti-Comintern pact with Germany (they were joined by Italy the next year), and in 1937 the empire began its brutal invasion of China.

When the Consulate-General left the bustle of Collyer Quay for its quieter offices on Mount Emily in 1939, the Japanese Empire was isolated on the world stage and dangerously alienated from its former British allies. Its new offices were likewise isolated from the power centers on either side of the Singapore River and had turned its gaze back to the traditional core of Little Japan. For a time, the Japanese had been one of the most influential expatriate populations in Singapore, but nationalism among the local community and imperial expansion abroad left this community smaller and more insular. The Second World War, and the repatriation of almost all Japanese residents after 1945, brought this chapter of Singapore’s history to a definitive end.

This project was supported by the National Heritage Board’s Heritage Research Grant.

Notes

-

1. Nan’yō Nichinichi Shinbun [South Seas Daily Newspaper], 1914–1941.

2. Nan’yō oyobi Nihonjinsha (Ed.). (1938). Nan’yō no gojūnen: Shingapōru o chūshin ni dōhō katsuyaku. Nan’yō oyobi Nihonjinsha.

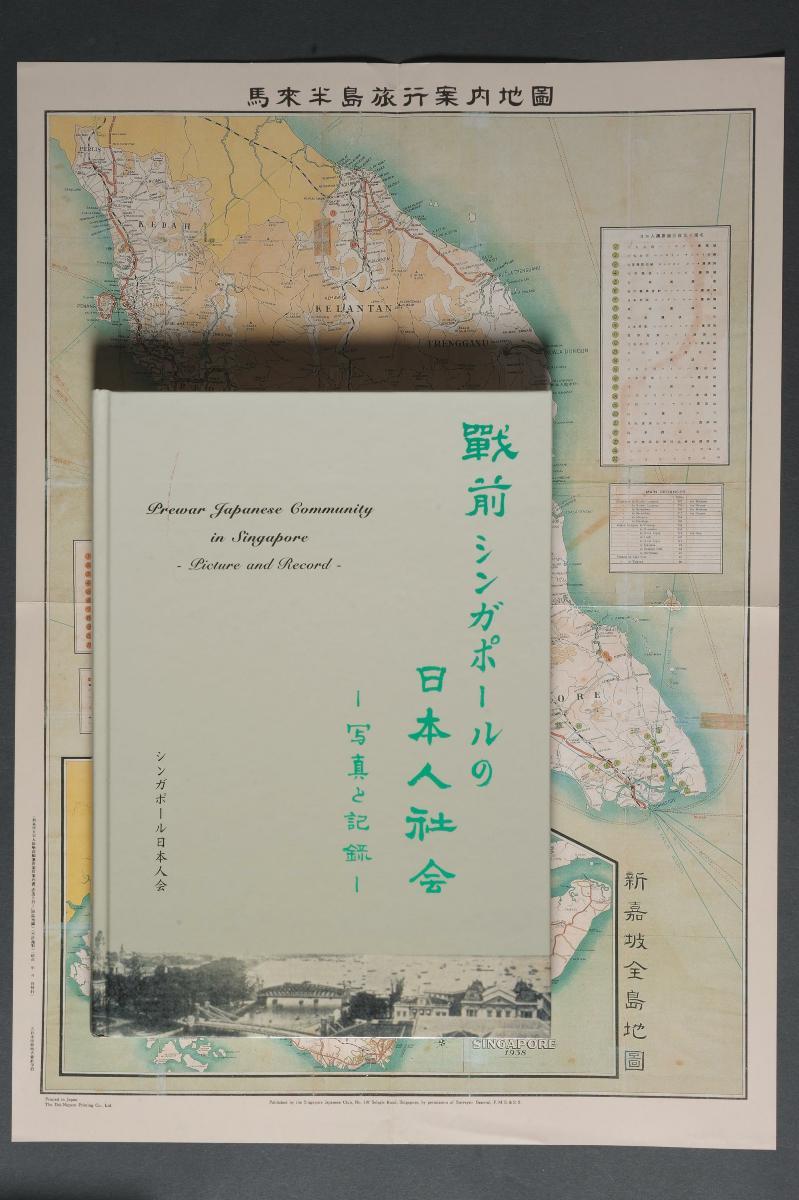

3. Shingapōru Nihonjinkai (Ed.). (1998). Senzen shingapōru no Nihonjin shakai: shashin to kiroku. Shingapōru Nihonjinkai.

4. Shingapōru Nihonjinkai (Ed.). (2016). Shingapōru Nihonjin shakai hyakunenshi: Hoshizukiyo no kagayaki. Shingapōru Nihonjinkai.

5. Shingapōru Nihonjin Kurabu (Ed.). (1939). Sekidō wo iku: Shingapōru annai. Shingapōru Nihonjin Kurabu.

6. Stoler, Ann Laura. (2010). Carnal knowledge and imperial power: Race and the intimate in colonial rule (2nd ed.). University of California Press.

7. Yano Tōru. (1975). “Nanshin” no keifu. Chūō Kōronsha.

.ashx)