TL;DR

Heritage has a positive social impact on wellbeing and health. Wellbeing, a dynamic and individual concept, is influenced by heritage through volunteering, visiting, sharing, healing, place, and environment. Heritage, encompassing tangible and intangible assets, processes, and practices, has been shown to enhance wellbeing through various case studies. Examples include volunteering at historic sites, the wellbeing benefits of visiting historic sites, digital platforms supporting life stories, heritage-led programs improving school attendance, and large-scale regeneration projects. These examples demonstrate the potential of heritage to positively impact mental health and wellbeing, addressing specific issues and inequalities. Heritage, when activated for wellbeing, can serve as a powerful mediator for societal transformation.

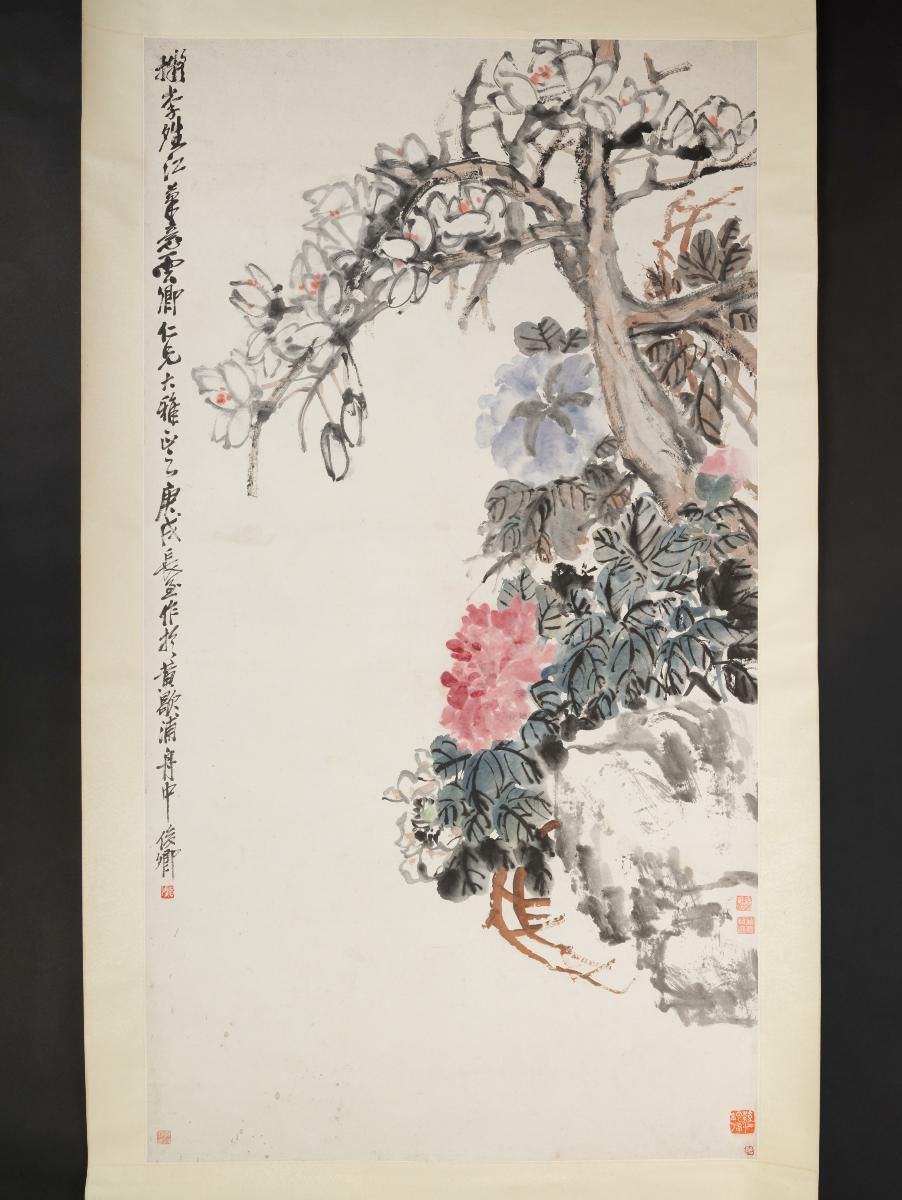

A framework for wellbeing and heritage. (Image courtesy of Historic England)

In 2002, Historic England published a Wellbeing and Heritage Strategy which set out our intention to focus on better understanding what capacity exists within the heritage sector to create positive social impact, especially through the lens of wellbeing and health.

Wellbeing is both an individual and social construct. Individual perceptions and experiences of wellbeing are shaped by wider social perceptions and practices, and are linked to social norms and values. Wellbeing can be understood as “how people feel and how they function, both on a personal and a social level, and how they evaluate their lives as a whole”[1]

Wellbeing itself is dynamic and subjective, making it very hard to understand and capture through general theories, so we decided to consider the ways in which heritage can help deliver wellbeing to individuals through a framework considering the following aspects — volunteering, visiting, sharing, healing, place and environment. This allowed us to organise our thought around the primary gateways through which heritage can deliver wellbeing impacts.

One might think about heritage as being one or more of the following elements:

-

Asset: This refers to tangible heritage, such as objects or places, valued for their aesthetic, architectural, historical, scientific, social, spiritual, linguistic or technological significance.

-

Practice: Often called “intangible” heritage and refers to ritual or traditional practices, cultural traditions such as food or storytelling, festivals or religious practice.

-

Process: Heritage can be understood as an individual or collective process of constant rethinking and redefinition of values.

A series of case studies below will show examples of wellbeing derived from heritage, each culminating in an insight into the transformative potential of heritage to transform lives and communities.

VOLUNTEERING

Research commissioned by Historic England looked at volunteers and community leaders involved in safeguarding and preserving historic sites, particularly those categorized as “heritage at risk”. The study identified key areas that were important to the wellbeing of the participants. Some aspects such as self-expression, identity affirmation, meaningful contributions, physical activity, and self-esteem, were general and applicable to volunteering in other domains. Others related specifically to the heritage context, as well as the sense of protecting something at risk of loss or under threat. The reassurance that change over time is possible in these sites, and satisfaction in helping achieve that change, such as creating a meaningful legacy, was clearly linked to individual wellbeing aspects such as self-esteem and self-actualisation.

A historic swimming pool and bath in Birmingham is an example of a community project which is aimed at using a historic asset to create community benefit. Moseley is a suburb of Birmingham—an area with a mixture of affluence and deprivation with a population of 22,000 , sitting within the Midlands city of Birmingham (population of 1.2 million). Moseley Road Baths is the only bath in the UK built before 1914 to have continuously hosted swimming since its opening in 1907; a friends group was set up in 2006 and, in 2018, the operation of the Baths was moved from the local authority to the community group.

The project which includes Moseley Road Baths and Balsall Heath Library began a major £32.7 million capital redevelopment project to repair, restore and transform these two heritage buildings in the heart of the Balsall Heath community in South Birmingham, bringing the building back into functional use and establishing a long-term sustainable future for the site. Accompanying this project is a creative and life-enhancing programme of community engagement, supported by thorough community consultations and the piloting of various activities. The success of the restoration project depended on volunteers from within the community.

These two projects show how heritage creates wellbeing for all. There is potential to ensure that heritage projects, whether through volunteering at one place or supporting a larger project for a community in a heritage setting, reach many people and support their mental health in many ways.

Moseley Road Baths, Birmingham. (Photo courtesy of Historic England)

VISITING

There is growing research on the wellbeing benefits of visiting historic sites, moving from a generic understanding of overall wellbeing benefits to explaining the impact of visiting historic sites on specific aspects of wellbeing. This can provide valuable insights for those operating the heritage sites or assets to understand how the heritage element under their care contribute to specific wellbeing impacts on visitors. Led by the University of Southampton, a research project examined the ways in which people were using heritage sites to support their wellbeing during COVID-19 from June to October 2020. 780 questionnaires and 328 interviews, participant observation and ethnography formed the basis of the research, which focused on unmediated visits only (interpretation strategies were not within the research scope).

The research findings reveal the importance of visits to heritage sites in promoting positive subjective wellbeing as well as satisfying deeper psychological and socio-cultural needs. There was clear evidence that such visits reduced anxiety and strengthened social and family connections, as well as building trust through autonomy and control. Visits provided people with a sense of ontological security (stability in the sense of self and one’s place in the world) that is fundamental to wellbeing and reduces susceptibility to anxiety.

Visiting historic sites is about more than enjoyment and leisure. Such visits also impact anxiety reduction, mental health, population wellbeing and a sense of engagement and belonging.

Glastonbury Tor, Somerset. (Photo courtesy of Historic England)

SHARING

Worcester is a city in the west of England with a population of 100,000; although the county in which it sits, Worcestershire, performs well on many measures that relate to ageing, it does have an increasing rate of dementia diagnosis. Forecasts indicate a 56% increase in the number of people with dementia from 9,560 in 2019 to 14,905 by 2035. Two digital platforms were created to provide support for this growing group.

Know Your Place Worcester is a free online resource hosted by Worcester City Council. The interactive website is based on different maps of Worcester, which allows people to overlay and compare maps from different times and see how areas have evolved over the years—more maps will be added over time. Users can access various images, memories and records uploaded by others, as well as a whole host of digitised photographs and Historic Environment Records (archives of information and images held by local authorities). Users can also upload their own photographs and memories of Worcester to be shared with other users.

This platform has been linked to a focus on the development of “life stories”. “Life stories” are often understood to be a support for people with dementia, but the process of capturing information about what is important to you can be interesting and relevant for anyone. There is evidence that it can make a difference for people across the lifespan, including not just people with dementia but also those with learning disabilities and children who have been in the care system. Life Stories Herefordshire and Worcestershire is a free online platform that allows anyone living in either Herefordshire or Worcestershire to create their own digital life story book. There are different ways you can use the book, such as for your own pleasure and wellbeing, to encourage connection with others, leave a legacy, or as a group.

These case studies show us how heritage can be a catalyst for connection and sharing. While social isolation and loneliness are recognised as the most reliable predictors of mental health outcomes across the lifespan, heritage has been shown to allow people to feel more connected to their local area.

Worcester Life Stories. (Photo courtesy of Worcester City Council)

HEALING

The UK government in power at the time of writing (the Rishi Sunak premiership from 2022-4) identified that “improving [school] attendance is everyone’s business. The barriers to accessing education are wide and complex, both within and beyond the school gates, and are often specific to individual pupils and families”. School attendance not only impacts on achievement and grades, but also a child’s self-perception, including how they see themselves as a learner and their ability to build trust and supportive social connections. And as the government makes clear—it can be an important protective factor.

Historic England designed a programme, Rejuvenate, which was heritage-led and involved working outdoors with cultural practices, creativity, archaeology and heritage understanding. School children showed a demonstrable, measurable improvement in engagement with learning and attendance as well as increased confidence, social connection and feelings of pride. Surveys recorded an increase in the school children feeling recognised for their achievements and in having their voice heard.

Both the Rejuvenate group and a control group started at the same levels of low attendance but experienced a divergence after the programme’s intervention. Left unsupported, the control group’s attendance worsened whereas the Rejuvenate group showed positive improvements in weekly attendance of on average of 4.3%. 2 children showed an improvement of over 10%—which equates to 15 days of learning per year. This project could double the chances of some children reaching their potential.

As a quote from a form tutor puts it:

“All of my tutees that have participated have seen improvements in various areas such as self confidence and self-esteem, confidence in interacting with others, pushing themselves out of their comfort zones (e.g., putting themselves in somewhat unfamiliar situations) and so much more. I have been really impressed with their growth this year, especially recently, and a big part of that has been this project.”

The positive results of Rejuvenate demonstrate the power of discovery that heritage practice and archaeology provide. The programme links directly to teamwork and self-discovery, which nudges the child towards a greater self-determination, which is essential in empowering vulnerable children to counter their circumstances, have self-confidence in their own abilities and to discovery their own unique value.

Photographing finds at Coombe Bissett, as part of the Rejuvenate project. (Photo courtesy of Wessex Archaeology)

PLACE

Two large scale regeneration projects serve as examples of the benefits of place-based restoration and related community engagement.

In the Midlands city of Coventry, some streets which had suffered from long-term neglect were part of a national £95-million government-funded scheme delivered by Historic England aimed to unlock the potential of high streets across England, fuelling economic, social and cultural recovery for current and future generations. Some achievements reported as part of the scheme so far include:

-

9 apprenticeship schemes

-

160 “other professional training” activities

-

54 construction training activities

-

230 school education events/activities

-

103 training events/activities to volunteers

Kirkham is a town in the North-West of England which used a portion of funds for a cultural programme to accompany the wider scheme of core regeneration works. Kirkham chose to theme the whole cultural programme around health and wellbeing for its local community. The city undertook a feasibility study in 2021 and co-created a programme of works from 2021-2024 with the local council, church, library, museums, charities, public health and primary healthcare as key partners. It ended up creating a new local archive, cookery and food-based links to Kirkham’s past, heritage-based activities, which included “nature and nurture” programmes, exploring the local church, movement programmes exploring a range of dance styles as intangible cultural heritage. Some tangible outputs of the programme included a town trail,a new tapestry based on the history of Kirkham and a collection of oral histories and memories. The programme was particularly impactful in addressing loneliness in Kirkham.

These cases show how heritage can support the two key aspects of wellbeing identified in the Historic England Wellbeing and Heritage Strategy: that of the social determinants of health (such as skills and education) and the life satisfaction that being involved and being part of a community brings to individuals.

Conventry High Street Heritage Action Zone. (Photo courtesy of Historic England)

CONCLUSIONS

How we develop our places and spaces and how we present our cultural heritage is testament to our beliefs and is a conscious act of creating a future we want to see. In this way, we are the producers of our own legacy. We might think about how we need to protect that which has value and significance, and appreciate how its very presence is an asset for a life of good quality; and following on from this is the question of how we enhance our environment; and also, how we activate heritage for social good.

We know from experience that there are some general principles that gives a wellbeing project a greater chance of success — to identify local needs, research what works, to work with partners, have clear wellbeing goals, co-create design and evaluation and undertake reflective learning.

We have begun to see the value of heritage to the wellbeing of our population and also how we can begin to tailor heritage interventions to address particular health and wellbeing inequalities. The examples elaborated in this article aim to indicate the opportunities offered by heritage work to deliver both protective factors for mental health and wellbeing and to address specific issues. By activating heritage for wellbeing, I truly believe that it can reach its potential as the ultimate mediator for wellbeing and positively address inequalities, transforming society for the better.

Notes

-

1. New Economics Foundation Citation 2012, 6.

2. Levula, Wilson, and Harré Citation 2016.