TL;DR

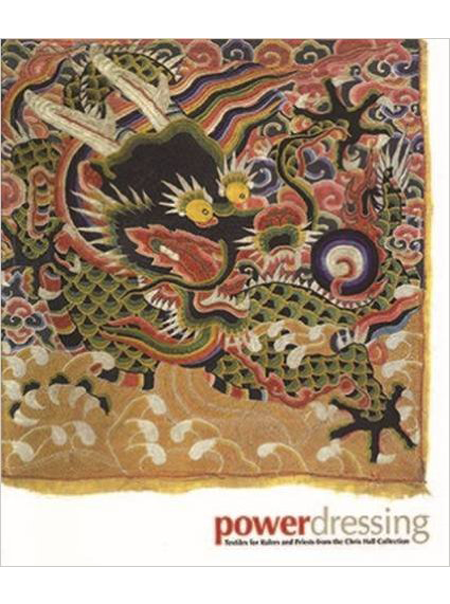

The Peranakan Museum presents "Fukusa: Japanese Gift Covers from the Chris Hall Collection" (19 April – 25 August 2024), showcasing the customs and spectacle of gifting in Japan through fukusa and related textiles. The exhibition explores the changing significance of fukusa from the late 18th to early 20th centuries and highlights the use of textiles in gifting customs across cultures.The act of gifting is deeply ingrained and takes many forms across histories and cultures. Gifts reflect who we are and bind us together. The way something is given is equally significant, as it is often the customs and accoutrements of gifting that transform “things” into gifts. Fukusa: Japanese Gifts Covers from the Chris Hall Collection delves into the customs and spectacle of gifting in Japan through a group of fukusa (gift covers) and related textiles.

Although largely overlooked in the study of Japanese art today, fukusa feature exquisite embroidery, weaving, dyeing, and painting, and are some of the finest examples of Japanese textile artistry. They were ubiquitous for many in the Edo (1603–1868), Meiji (1868–1912), and Taishō (1912–26) periods, facilitating the exchange of gifts and honouring both the giver and the recipient through the design. In the late nineteenth century, fukusa were also highly successful exports that played a role in defining Japan as it emerged as a global power. This exhibition traces the use and changing significance of fukusa from the late eighteenth to early twentieth centuries, as Japan transformed from a relatively isolated island nation to a key player on the world stage. It celebrates a gift of Japanese art from the renowned textile collector Chris Hall to the Asian Civilisations Museum.

The art of giving

The term “fukusa” encompasses both cloths used in Japanese tea ceremonies and textile gift covers, which are sometimes known as kake fukusa. They are generally squarish in shape and made of lined silk. They differ from the more commonly known furoshiki, which are used to wrap objects and are typically made of unlined cotton or hemp.

The practice of formally presenting gifts with fukusa began in the late seventeenth or early eighteenth century. They were initially used by the ruling warrior class (samurai) and nobility (fig. 1). By the early 19th century, well-to-do merchants had embraced the lifestyle and customs of the upper classes, including exchanging fukusa. This practice continued among wealthier members of Japanese society throughout the Meiji period and well into the 20th century. The gift was usually placed on a lacquer box or tray and covered with a fukusa. Each fukusa was carefully chosen to evoke the occasion and convey a message to the recipient through its design. Exhibition displays show how they were presented over gifts, for example draped or folded in thirds or quarters (fig. 2).

Fig. 1

Presenting a gift covered with a fukusa

Ishikawa Toyonobu (1711-1785), Picture Book of Ladies’ Etiquette (Ehon Edo Murasaki)

Woodblock-printed book, 1765

National Diet Library, Tokyo, 寄別5-5-3-9.

Fig. 2

Fukusa with phoenix, autumn leaves, and flowers

Late Edo or Meiji period, 19th century

Gold thread, silk satin appliqué, and embroidery on silk satin

61.5 x 70 cm

Asian Civilisations Museum, Gift of Chris Hall

The recipient would accept the gift and admire the cover, and only then was the sentiment behind the gift fully realised. A fukusa featuring boys at play conveys the wish for many descendants and celebrates children (fig. 3). The family crest on the corner of the lining reveals how it was presented—folded with the crest facing up and the main design on the inside. When a fukusa was folded this way, the recipient would request the honour of seeing the rest of the design. A small return gift was placed on the tray or box, covered by the same fukusa, and sent back to the giver.

Fig. 3

Fukusa with boys at play (front and back)

Meiji period (1868–1912)

Gold thread and paste-resist dyeing (yūzen) on silk crepe

74.5 x 67.4 cm

Asian Civilisations Museum, Gift of Chris Hall

Fukusa and fashion

Like clothing in the stylish world of Edo Japan, fukusa showed off the taste, wealth, and status of their owners. Many fukusa followed the latest fashions and display lavish techniques or designs. These were periodically restricted by sumptuary dress laws. Clothing was closely tied to class, and the rules aimed to prevent people from dressing above their social status. Some fukusa feature "palace landscape" (goshodoki) designs, characterised by literary motifs scattered in stylised landscapes, that were otherwise reserved for warrior-class clothing (fig. 4). Others are patterned with “fawn spot” tie-dye (kanoko shibori), a costly and labour-intensive decorative technique favoured by the warrior and merchant ranks that was often the target of sumptuary regulations (figs 5, 6).

Fig. 4

Fukusa with war fan and headdress

Edo period, late 18th or 19th century

Embroidery, gold thread, “fawn spot” tie-dye (kanoko shibori), and paste-resist dyeing (yūzen) on silk crepe

95 x 98.4 cm

Asian Civilisations Museum, Gift of Chris Hall

Fig. 5

Detail of the above

Fig. 6

Outer kimono with pine and cherry blossoms

Late Edo period, 19th century

Embroidery, gold thread, stitch-resist tie-dye (nuishime shibori), and “fawn spot” tie-dye (kanoko shibori) on figured silk satin

164.5 x 123 cm

Asian Civilisations Museum, Gift of Chris Hall

Journeying through life

Fukusa were used for all types of occasions that required gifts, from annual seasonal festivities to important personal events. Each fukusa conveyed a sentiment or message, from congratulations to condolences, through symbolic motifs or complex pictorial allusions. For instance, fukusa decorated with a feather robe (hagoromo) conveyed kindness and reciprocity, while those with the shell-matching game (kai-awase) symbolised a well-matched couple, highly suitable for weddings (figs 7, 8). A gift was not considered successful unless the recipient understood the meaning behind the decoration, and while deciphering the message behind each design can be difficult for the modern viewer, it would have showcased the erudition and cultural sensitivity of both the giver and recipient. On display are fukusa used to celebrate births and new beginnings, weddings, educational and professional accomplishments, and old age.

Fig. 7

Fukusa with feather robe

Late Edo or Meiji period, 19th century

Gold thread and embroidery on silk satin

80.8 x 65.5 cm

Asian Civilisations Museum, Gift of Chris Hall

Fig. 8

Fukusa with shell-matching game (detail)

Meiji period (1868–1912)

Gold thread, embroidery, and paste-resist dyeing (yūzen) on plain weave silk

72.5 x 67.4 cm

Asian Civilisations Museum, Gift of Chris Hall

Japan on the world stage

After Japan opened to global trade in the 1850s, fukusa were some of the most coveted Japanese objects in Europe and America. They were appreciated for their pictorial and decorative qualities, rather than as objects used in ceremonial exchange. Paintings, photographs, and written records attest to the display of textiles like fukusa in European and American interiors and the widespread admiration of the painterly qualities of Japanese embroidery (fig. 9). They were highly successful exports and inspired new types of decorative silks made for foreign markets, such as fine art textiles (bijutsu senshoku). Representing Japan at world fairs and other foreign venues, the style and motifs from these decorative silks increasingly became a national style both overseas and at home, and shaped Japan’s identity as it emerged as a global power.

Domestically, Meiji initiatives to industrialise and modernise Japan introduced new technologies and ideas, rapidly changing the way textiles like fukusa were produced and used. This section includes fukusa that would have been admired and collected in the West, as well as new types of fukusa that emerged in this period, such as examples made with cutting-edge weaving and dyeing technologies or imported European cottons (fig. 10).

Fig. 9

The Japanese room in the William H. Vanderbilt House, New York, with a framed fukusa on the wall.

Edward Strahan (Earl Shinn), Mr. Vanderbilt's house and collection, Boston, 1883–84.

The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York [106.1 V28 F].

Fig. 10

Two fukusa with 19th-century European cotton

Meiji or Taishō period, late 19th or early 20th century

Printed cotton

Each 73 x 66 cm

Asian Civilisations Museum, Gift of Chris Hall

Coda: Textiles and gifts across cultures

Fukusa are just one example of textiles used in gifting. In many cultures, especially before the introduction of modern technology, weaving and decorating cloth was a laborious task. Fine fabric was extremely precious. Wrapping, covering, or accessorising a gift with valuable cloth was both practical and luxurious. Textiles also play a crucial part in Peranakan gifting customs. Tray covers with auspicious motifs are used to exchange wedding presents (fig. 11). Vibrant cloths decorate the front of altars, where offerings to ancestors and deities are made during religious ceremonies, birthdays, and weddings (fig. 12).

Fig. 11

Dowry tray cover

Malacca, early or mid-20th century

Silk satin, silk floss, metal thread

Peranakan Museum

Fig. 12

Altar cloth

Java, Indonesia, 1920 or 1930s

Cotton (drawn batik)

Peranakan Museum, Gift of Matthew and Alice Yapp

By presenting historical examples of textiles related to gift giving, this exhibition encourages visitors to reflect upon the act of gifting in our own time and place, as well as the rituals and materials we engage with when we give presents to others.

Notes

- McDermott 2010

Hiroko T. McDermott. “Meiji Kyoto textile art and Takashimaya.” Monumenta Nipponica 65, no. 1 (2010), pp. 37–88. - Sapin 2004

Julia Sapin.

“Merchandising art and identity in Meiji Japan: Kyoto nihonga artists’ designs for Takashimaya department store, 1868–1912.” Journal of Design History 17, no. 4 (2004), pp. 317–36. - Stinchecum 1984

Amanda Mayer Stinchecum. “Kosode: Design and techniques.” In Kosode: 16th–19th century textiles from the Nomura Collection. Exh. Japan House Gallery, New York, 1984, pp. 22–57. - Takemura 1991

Akihiko Takemura. Fukusa: Japanese Gift Covers. Tokyo, 1991.