TL;DR

A science graduate’s year-long volunteer stint at HCC reveals the hidden world of art preservation. Her involvement in a project on Chinese ink analysis in Nanyang style paintings showcases advanced tech in conservation, including AI, for non-invasive conservation techniques. This interdisciplinary approach in heritage science, and her experience and public engagement, has inspired her to further studies in archaeological science, aiming for future real-world applications.Entering the World of Heritage Conservation

When I first knocked on the door of the HCC, Kathleen Lau, the senior manager, greeted me with a warm smile. “I’m a recent science graduate from NUS, passionate about conservation science and seeking volunteer opportunities,” I said excitedly. She kindly introduced me to the team, and soon I was involved in a fascinating project led by conservation scientist, Lynn Chua and Senior Conservator (Paper), Lee Siew Wah. The project focused on the scientific analysis of Chinese ink in Nanyang style paintings. At that moment, I realised I had entered an extraordinary world where my scientific skills could be applied to preserving and understanding tangible heritage.

The year-long ink identification project gave me valuable insight into the behind-the-scenes work of conservators and conservation scientists, as well as innovative ways to integrate machine learning into heritage science. Furthermore, it offered valuable outreach experience, allowing me to share our techniques and findings with the public. Overall, this experience fostered a holistic connection from the lab to digital platforms and ultimately to the museums.

The Role of Science and Technology in Conservation: Case Study on Cheong Soo Pieng's Drying Salted Fish

The Drying Salted Fish painting by Cheong Soo Pieng is a prominent painting in our art historical narrative and has been reproduced on the back of Singapore’s fifty-dollar note. This ink-on-silk artwork is believed to utilise a variety of ink types, reflecting Cheong's renowned experimentalist approach with different media and inks. While much research in heritage science focuses on colour pigments, the uniqueness of our study lay in identifying the types of black ink used in the painting. Gaining more information about the ink offered valuable insights into Cheong’s artistic practices and helped us design conservation methods for each specific ink type.

Drying Salted Fish (1978) by Cheong Soo Pieng. Photo credit: National Gallery Singapore.

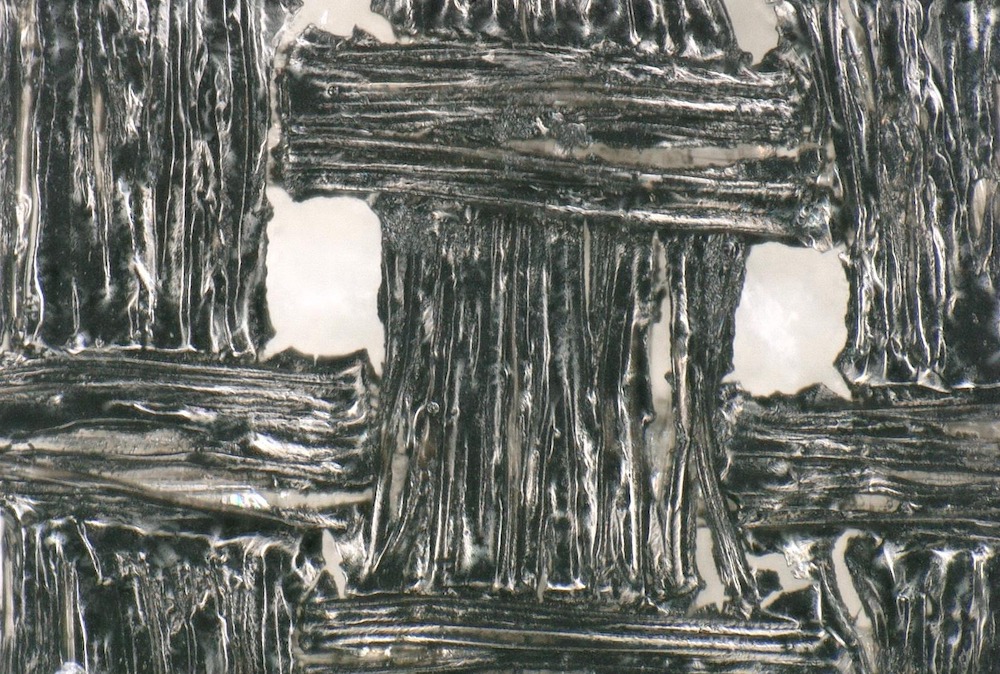

Our approach involved creating mock-ups of various inks that would have been available to the artist at that time—watercolour, gouache, Chinese ink stick, Chinese liquid ink, and Indian ink. These inks were carefully painted on silk support and then reinforced with a lining of Chinese paper using starch. Peering into the microscope, I was surprised as the silk fibres appeared to be in large bundles of thread, and the ink particles revealed interesting details. The watercolour had a sandy, matte appearance, contrasting sharply with the glossy, shiny quality of the Chinese liquid ink. Witnessing these differences first-hand was a profound moment for me, igniting my passion for using familiar scientific skills to resolve conservation problems.

Preparing the mock-ups. Photo credit: Lynn Chua.

Microscopic image comparison between watercolour (left) and Chinese liquid ink (right). Photo credit: Jiao Zijin.

The most exciting yet time-consuming part of the project was training a machine learning model to recognise the microscopic characteristics of the different ink types. To mitigate the subjectivity inherent in human analysis, we experimented with multiple models. This involved gathering over 2,000 cropped and edited microscopic images, for training the model. Throughout this experience, I faced various challenges, particularly with machine learning. As someone not initially well-versed in this area, understanding the model parameters was daunting. However, after consulting with GovTech professionals, our team gained valuable insights, which helped clarify our doubts and deepened our understanding of the technology.

While managing the large volume of microscopic images, I found ways to streamline the editing process by researching and using software that minimised manual work. This significantly improved our efficiency in photo editing. Integrating technology into the workflow highlighted its growing role in conservation science. A key aspect of the project was the collaboration between conservation scientists and machine learning experts, which underscored how technological advancements can enhance non-invasive methods in heritage preservation. This partnership also offered opportunities for us to consult with professionals on machine learning biases and algorithms, refining our approach to analysing heritage objects.

Interestingly, my background in biological research, where I used specialised software to analyse cells, proved useful in this project. I applied similar analytical techniques to examine ink particles, creating a fascinating link between the two fields. This interdisciplinary application reinforced my belief in the value of cross-disciplinary methods in conservation science.

Throughout the project, I deepened my understanding of the significance of non-invasive techniques (the practice of not causing any harm to our artefacts) in preserving artefacts. It requires a delicate balance to protect heritage objects while ensuring accurate scientific analysis. Working with a diverse team of experts and stakeholders, I realise that scientific approaches are capable of revealing insights that cannot be captured through oral histories or artist interviews. These objective findings provide reliable evidence, offering a form of deducible "hard truth" that remains constant and unalterable, unlike subjective interpretations or memories.

The Unseen World of Conservation: Behind the Scenes

Unlike the bustling museums filled with artefacts and curious visitors, one of the most fascinating aspects of my experience was witnessing the 'backstage' work of conservators and conservation scientists. Much of the public remains unaware of the meticulous efforts that go into preserving artworks. From understanding the artist’s techniques to applying the right conservation methods, there is an entire world of scientific investigation that operates behind the scenes. This unseen work reassures us that our artefacts are well cared for by conservation professionals, even when they are not on display. It was a privilege to be a part of this process, where each step brought us closer to unravelling the rich history and cultural values embedded in these objects.

From Lab to Gallery: Sparking Public Interest and Inspiring Young Minds

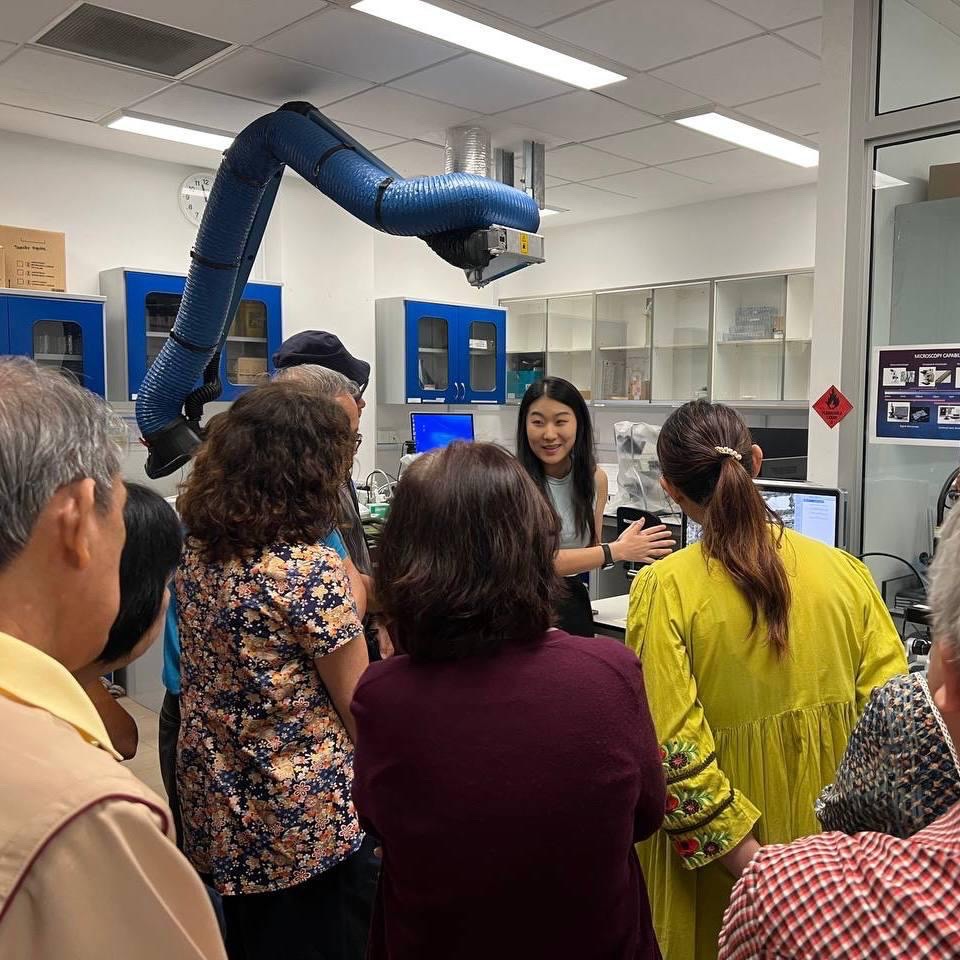

The final stage of our research involved capturing real microscopic images of Cheong’s artwork at the National Gallery Singapore, which we used to compare with our mock-up images. After collecting the images, I had the opportunity to engage with the public at the Cheong Soo Pieng: Layer by Layer exhibition, held at the Gallery from April 5 to September 29, 2024. Using zoomed-in images from our microscope analysis, I helped visitors visualise the tiny fibres in the artwork and the mosaic patterns of the inks. This outreach helped me explain complex scientific concepts in an accessible way, igniting interest in HCC’s behind-the-scenes work and highlighting the essential role conservation plays in preserving our cultural heritage.

HCC Conservation Science Team (Ivan Djordjevic, Lynn Chua) and Paper Section (Lee Siew Wah) at the National Gallery Singapore, explaining ink analysis using microscope images. Photo credit: Jiao Zijin.

Another highlight was introducing these concepts to young audiences. I participated in an outreach event with SingaScope (a consortium of microscope platforms in Singapore), NUS and Science Centre Singapore to demonstrate microscopy’s role in the preservation of historical artworks. We showcased cross-sections of paintings, the details of warp and weft of fabrics, and even pests like silverfish and dust mites that can damage artefacts. These interactive demonstrations fascinated visitors, especially children, who were amazed to see the hidden world within objects. Seeing their excitement was deeply fulfilling. This was also a valuable opportunity to introduce conservation to younger audiences, and it was clear that many students were eager to learn more about pursuing careers in conservation and conservation science.

Explaining Conservation Science to younger audiences. Curious children looking into a microscope to see painting cross-sections. Photo credit: Lee Shu Ying and Jiao Zijin.

Looking Toward the Future of Conservation

My outreach experiences at both the Gallery and Science Centre have provided numerous opportunities to engage the public and cultivate interest in conservation. Whether I was explaining the details of conservation to interested students or responding to questions from visitors at HCC, I found it incredibly fulfilling to share insights into this often-overlooked discipline. These interactions underscored the necessity of fostering awareness about the essential role that science and conservation play in preserving our cultural heritage.

Answering questions from visitors at HCC. Photo credit: Kathleen Lau.

Reflecting on these experiences, I am fortunate to have had the rare opportunity to combine hands-on research with public outreach and personal growth. This volunteer work not only deepened my understanding of the conservation process but also enabled me to share this knowledge with others, encouraging a greater appreciation for the synergy between science and the arts. Witnessing the enthusiasm of young audiences, I am inspired to build upon my passion for preserving our heritage in future.

I am particularly grateful to my mentors at HCC: our dedicated and inspiring conservation scientist and research supervisor, Lynn Chua; our very experienced and knowledgeable senior conservation scientist, Ivan Djordjevic; and senior conservator (paper), Lee Siew Wah. Their invaluable guidance, unwavering support, and expertise have profoundly shaped my journey. Additionally, I wish to extend my appreciation to all the directors for their insights and encouragement throughout my experience.

With a solid foundation gained at HCC, I am now pursuing a master’s degree in Archaeological Science at the University of Oxford, specialising in the material analysis of inorganic excavated artefacts and dye analysis in textiles to enhance preservation efforts. My year-long volunteer experience provided a valuable base, allowing me to adapt swiftly to the academic environment, where many familiar concepts have resurfaced in real-world applications. I look forward to future opportunities to apply my skills in safeguarding both the tangible and intangible aspects of our cultural heritage for generations to come.