TL;DR

The Peranakan Museum presents “Batik Nyonyas: Three Generations of Art and Entrepreneurship” (11 October 2024 – 31 August 2025), showcasing batiks made by three generations of Peranakan women from Indonesia—Nyonya Oeij Soen King, her daughter-in-law Nyonya Oeij Kok Sing, and her granddaughter Jane Hendromartono. The exhibition celebrates three notable gifts to the museum from Ika, Melia, and Inge Hendromartono, the family of Mr and Mrs Lee Kip Lee, and Mr Agam Riadi.The story of three nyonyas

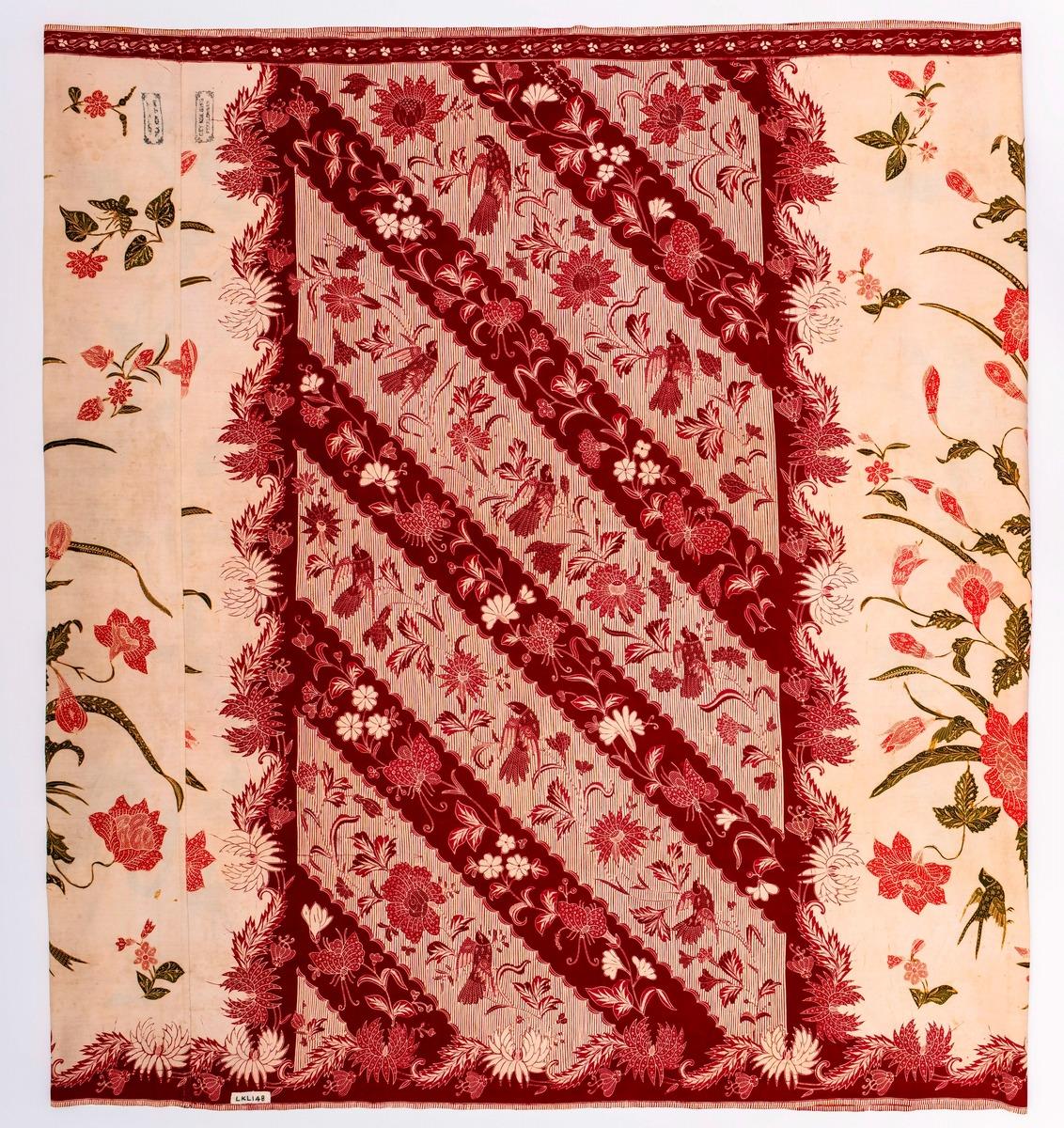

Family, art, and entrepreneurship converge at the Peranakan Museum in the story of three visionary Peranakan women from Indonesia—Nyonya Oeij Soen King, her daughter-in-law Nyonya Oeij Kok Sing, and her granddaughter Jane Hendromartono (fig. 1). From the 1890s to the 1980s, they produced impressive batiks in the renowned batik centre of Pekalongan on Java’s north coast.

Each generation of the Oeij family made batiks in their own distinctive style, unlike many traditional Asian family workshops where products were faithfully replicated from generation to generation. This exhibition explores their lives and works, revealing how each woman became a batik master in her own right, and how they ingeniously responded to the rapid political, cultural, and economic changes of their times to run a business that produced great art.

Batik is proudly celebrated as essential to Indonesia’s cultural heritage. This story allows us to experience its exceptional artistic legacy in an intimate, complex, and tangible way.

Nyonya Oeij Soen King (1871–1950)

Born in Pekalongan just as the town’s batik industry was beginning to develop, Liem Loan Eng (fig. 2) married Oeij Soen King in the late 1880s. Oeij, whose ancestors hailed from China’s Fujian province, lived in a row of three long houses in Pintu Dalam (now Jalan Blimbing) in the Chinese quarter. She was evidently steeped in the visual culture of Java and must have spent some years as a batik apprentice.

Nyonya Oeij began to produce fine batiks with technically challenging and visually complex designs from about 1900 to 1925. She ran her workshop from her home with a modestly sized but virtuosic team, creating just a small quantity of exceptional custom-made batiks for elite clients. These batiks were based on well-established patterns but included so many unconventional elements that they emerge as highly individual expressions. Her genius as an artist only becomes apparent upon close inspection, a luxury originally reserved for her patrons.

Today, only 18 batiks by Nyonya Oeij Soen King are known. They are not signed or marked but were preserved by her family for nearly a century. They are meticulously hand-drawn and use only natural dyes. All have a white background, where flaws would be more evident, which require the highest technical skill to produce. The dyeing process took about a month to complete.

The patterns have a profusion of animals and flowers, derived from Javanese, Indian, Islamic, Chinese, and European sources. These elements are combined with classic Javanese geometric patterns, set within established compositional frameworks (fig. 3). Yet Nyonya Oeij carefully avoided mechanical repetition through an irregular interplay of colour, motif, and filler pattern (isen). This improvisation within a set structure deeply influenced other batik makers, including her daughter-in-law, to whom she passed the business after her husband died in 1925.

Nyonya Oeij Kok Sing (1895–1966)

Nyonya Oeij Kok Sing (born Kho Tjing Nio, fig. 4) came from an old Peranakan family from Surakarta, and was the sixth generation of her clan. She grew up in a grand house in the heart of the Chinese district and was raised in a milieu where Hokkien Chinese traditions and Javanese court culture were deeply understood. In 1913 she married Oeij Kok Sing from Pekalongan, likely because of business links between their families.

Nyonya Oeij Kok Sing probably apprenticed with her mother-in-law, and by 1929 was already running the family workshop, which continued to produce only a limited number of one-off batiks for wealthy clients. Like many Peranakan entrepreneurs of her time, she was involved in several different enterprises, including producing herbal medicine and farming bird’s nest.

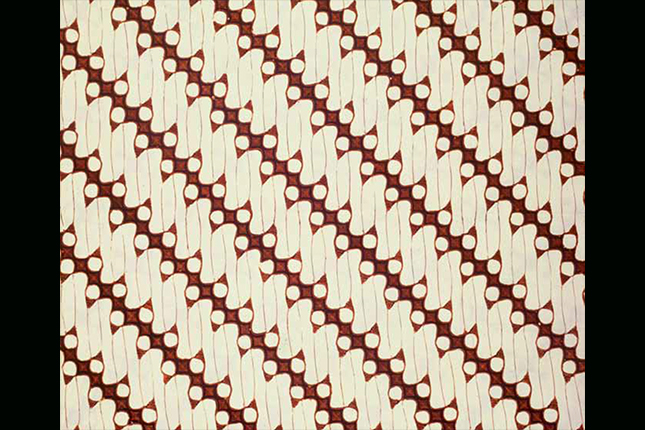

Nyonya Oeij Kok Sing started her career in the 1920s by producing conventional batiks of high quality (fig. 5). However, her batiks reached an exceptional level of brilliance after she took up the full range of new synthetic dyes in the mid-1930s. This design phase was marked by unconventional combinations of new colours, and striking, original patterns. Pastel shades were paired with flashes of acid colours, and leaves were outlined with electric pink and blue. Quirky new motifs crowded her backgrounds, including rice grains, clove buds, peacock feathers, and ornamental balls (fig. 6).

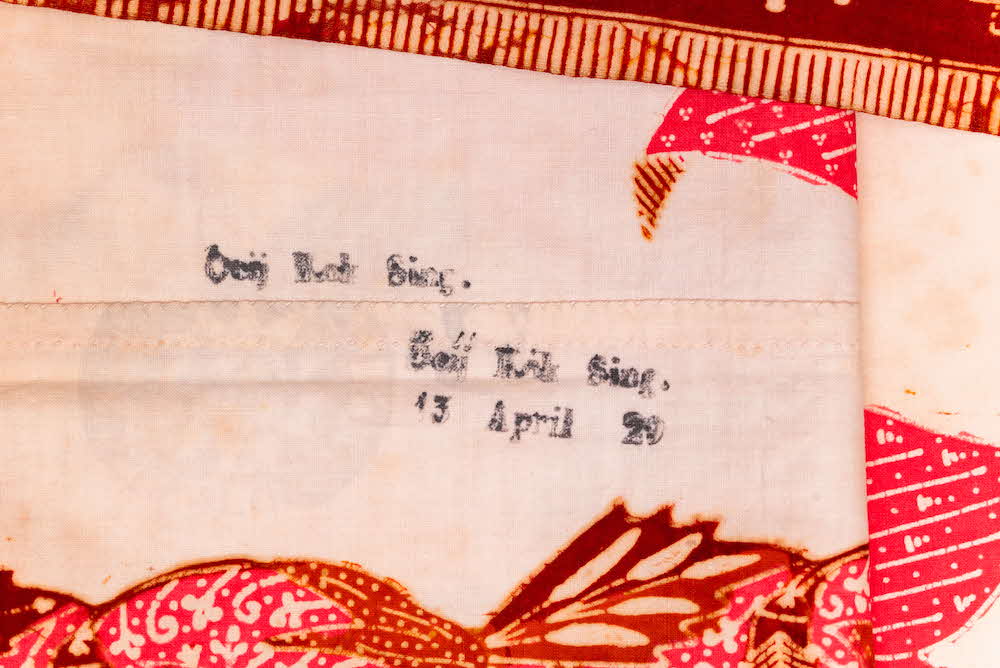

Fig. 5 Sarong, 1929. Nyonya Oeij Kok Sing. Cotton (drawn batik), 106 × 94 cm. Signed: Njonjah / Oeij Kok Sing. Stamped: Oeij Kok Sing. / 13 April 29 (earliest known date of Nyonya Oeij’s work). Peranakan Museum, Gift of the family of Mr and Mrs Lee Kip Lee, 2024-00360.

Nyonya Oeij is the only Indonesian artist who stamped her batiks with dates, including the day and month (fig. 7). Together with her signatures, this suggests that she was conscious of batik as an art form. Like her mother-in-law she seemed intent on producing complex masterpieces that could not be repeated, and by the late 1930s she was recognised as one of the top batik makers from Pekalongan. The reimagination of batik in such a vividly hued and contemporary way by a modestly dressed Peranakan nyonya is a high point not only of batik but of modernism.

Fig. 7 Sarong (detail), 1929. Nyonya Oeij Kok Sing. Cotton (drawn batik), 106 × 94 cm. Signed: Njonjah / Oeij Kok Sing. Stamped: Oeij Kok Sing. / 13 April 29 (earliest known date of Nyonya Oeij’s work). Peranakan Museum, Gift of the family of Mr and Mrs Lee Kip Lee, 2024-00360.

In the late 1930s Nyonya Oeij Kok Sing had already set her succession plan in motion by collaborating with her daughters. However, the disruptions of the 1940s were devastating for her and the batik industry. The death of her husband in 1941 was soon followed by the Japanese Occupation and then the armed struggle for Indonesian independence. Nyonya Oeij was forced to flee with her family to her ancestral house in Surakarta. Revolutionary turmoil there in 1948 led to a return to Pekalongan. Nyonya Oeij failed to reassemble her old team, and struggled to produce batiks of the same quality as in the 1930s.

Her youngest daughter, Jane (Djien Nio), collaborated most closely with Nyonya Oeij. Jane remained in Pekalongan to manage her mother’s workshop and maintain her business connections.

Jane Hendromartono (1924–1988)

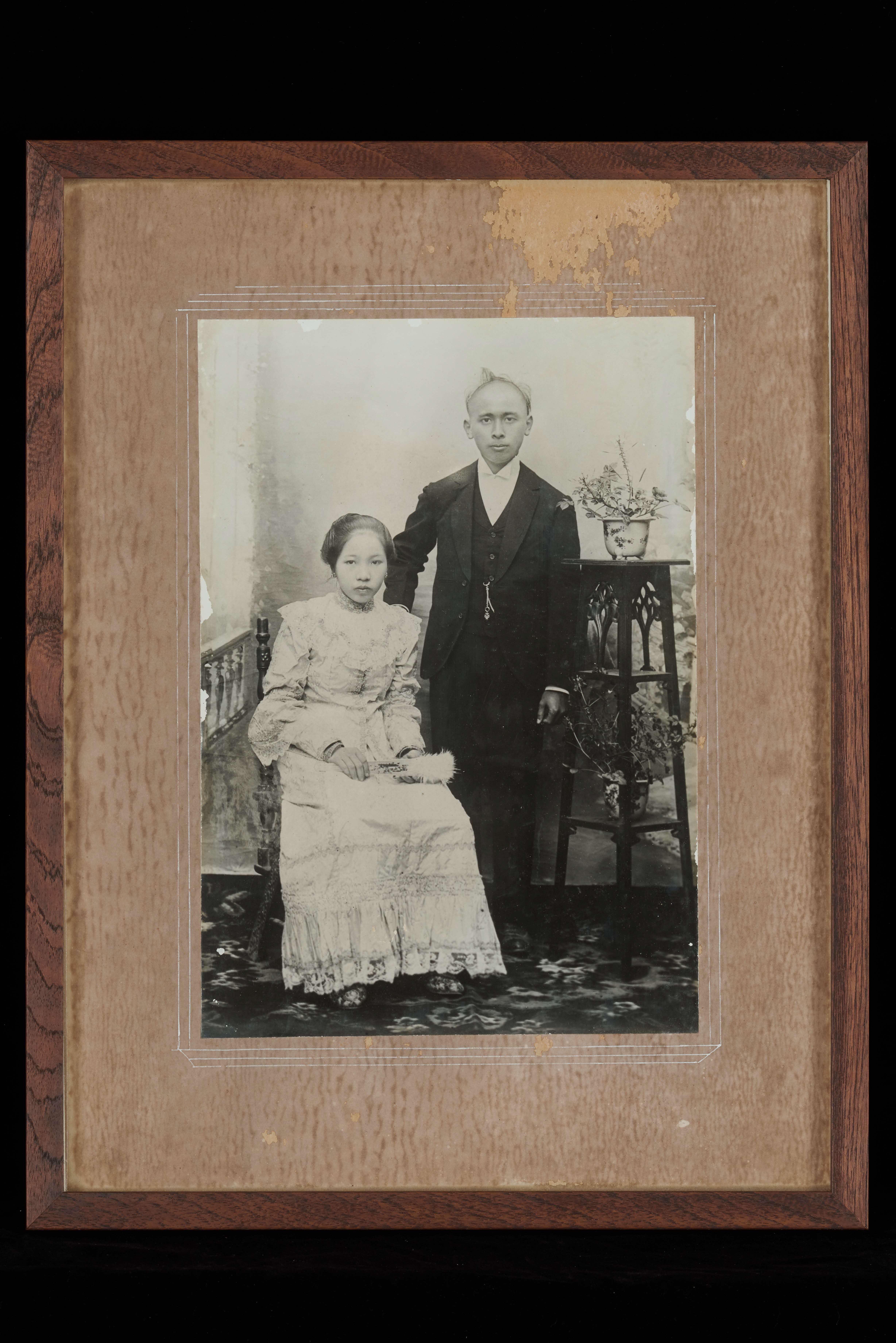

Djien Nio (仁娘, later known as Jane) was the youngest child of Oeij Kok Sing and Nyonya Oeij Kok Sing. She used several different names during her career. As her mother’s apprentice in the early 1940s, she initially worked under her mother’s name. After her marriage to Liem Siok Hien in 1947 (fig. 8), she took over the family workshop and signed batiks with her husband’s name. In 1967, when the Chinese in Indonesia were compelled to take Indonesian names, she adopted the name Jane Hendromartono and established Hendromartono’s Batik Art “Unique” as a new brand. Later works are often signed “Jane Hendromartono” and occasionally with her Chinese name, 仁. She worked tirelessly until ill health forced her to give up her business in the late 1980s.

Starting with high quality sarongs and kains, Jane responded to changes in market demand by producing her own versions of the viral “Kudus” style [1], then works in the new Batik Indonesia style initiated by President Sukarno. In the 1970s and 1980s, she began to revive her mother and grandmother’s designs for American buyers, contributing to Indonesia’s development of batik haute couture. The last stage of her career saw her focusing on mass produced block-printed fabrics for a global network of retailers and manufacturers.

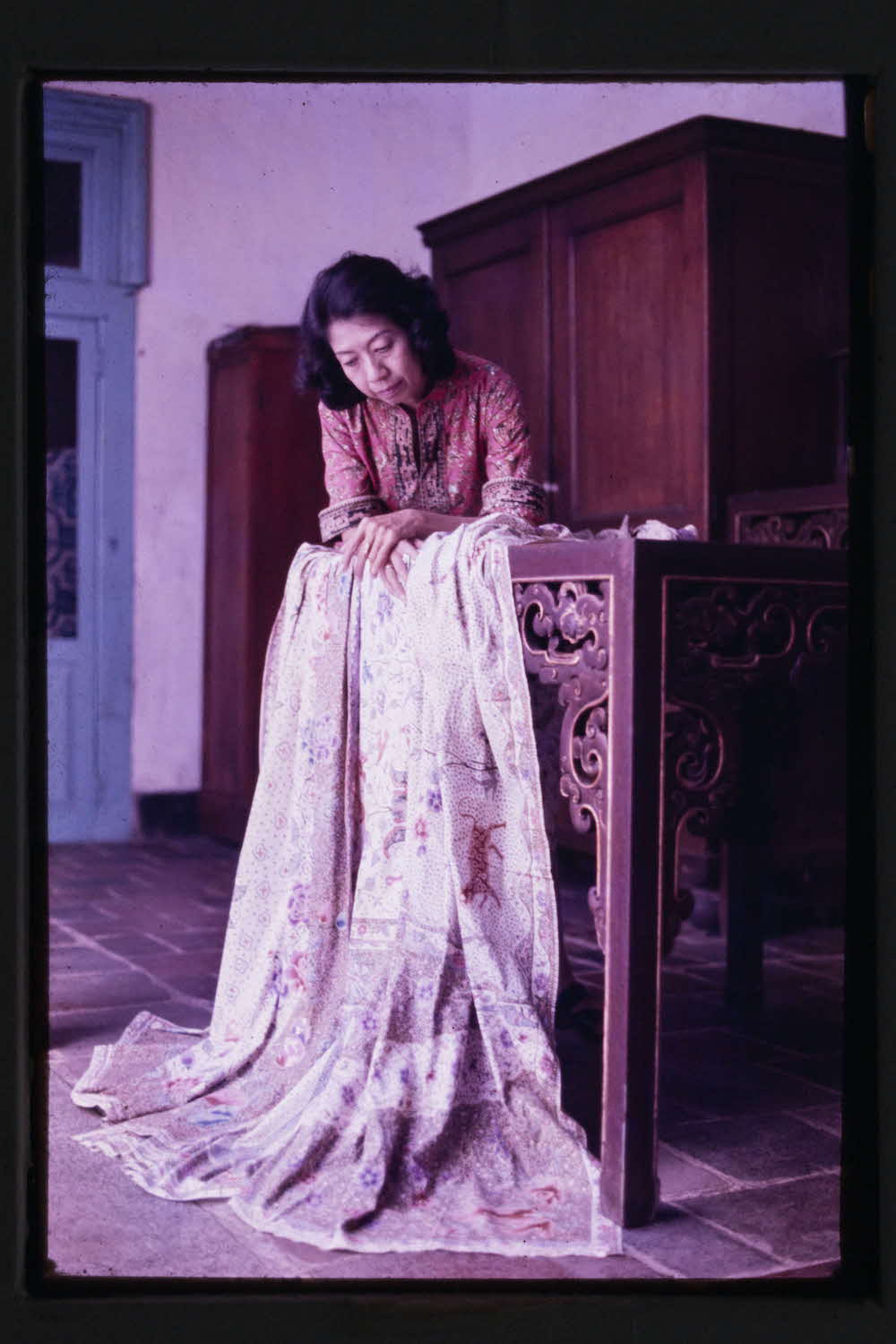

Each stage was marked by the use of different names, but the works that seemed most personal were signed “Jane Hendromartono”—such as her white ground batiks (fig. 9) and revival pieces. An intimate portrait of Jane taken with one of these works reveals the deep connection between her art and identity (fig. 10). Based on her family’s rich artistic legacy and her own devotion to batik as practice, her art embraced contemporary influences from around the world.

Fig. 9 Sarong, 1950s. Jane Hendromartono. Cotton (drawn batik), 105 × 211 cm. Applied signature: © / Jane Hendromartono / ’69 / Pekalongan – Java. Peranakan Museum, Gift of Ika, Melia, and Inge Hendromartono, 2017-00387.

Pushing boundaries: 1980s to present

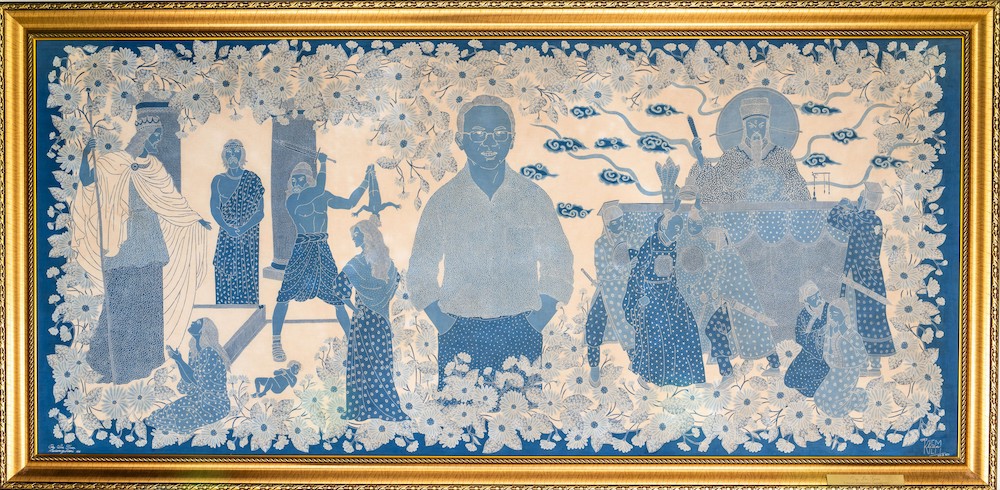

From the 19th century to the present day, women in Indonesia have been at the forefront of batik art and commerce, weaving a rich tapestry of tradition and innovation. Although UNESCO’s inclusion of Indonesian batik to its list of the Intangible Cultural Heritage of Humanity has bolstered the industry, contemporary female makers continue to navigate challenges, such as competition from mass-produced printed textiles and a shift towards sustainable practices. The exhibition’s final section explores how modern batik makers such as Asmoro Damais, Carmanita, Widianti Widjaja (fig. 11) and Insana Habibie honour their heritage while pushing creative boundaries. Their work not only preserves classic patterns but also introduces innovative designs, demonstrating the enduring vitality and adaptability of this art form. As batik evolves, these women stand as testament to its timeless appeal and its capacity for reinvention.

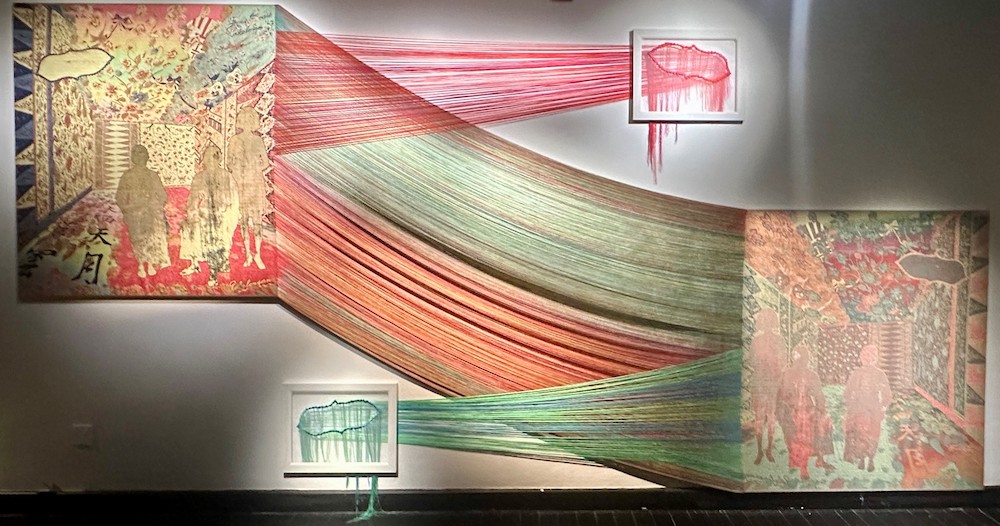

No Signature (A Study of Naming and Identity) by Aiko Tezuka

Commissioned by the Peranakan Museum, this work near the exit of the exhibition explores the complex identities of the three batik artists by considering home, art, and the passage of time (fig. 12). The interplay between machine-made and hand-worked techniques in the digital creation of a design, its machine weaving into a textile, the manual removal of threads, the addition of hand embroidery, and the manipulation of the fabric to reveal the front and back surfaces are all hallmarks of Aiko Tezuka’s work. These elements reflect on the development of the three women as daughters, wives, artists, and ultimately as individuals.

Fig. 12 No Signature (A Study of Naming and Identity), 2024. Aiko Tezuka (b. 1976). Berlin, Kyoto, Tokyo. Jacquard weaving (silk and polyester), embroidery, wood, 453.2 × 230 cm. Fabric development and production by Kaji Textile Inc. (Kyoto Nishijin Textile). Collection of the artist.