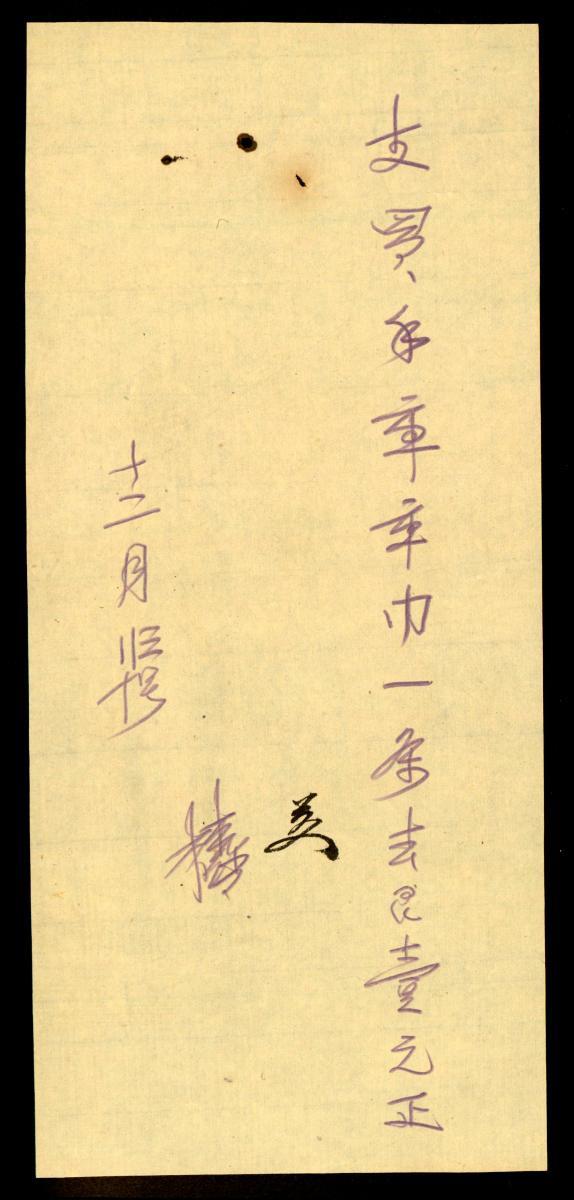

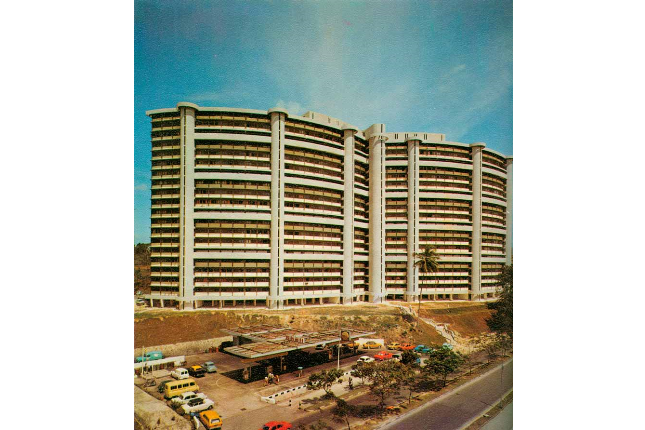

Crossing the Farther Shore is one of Dinh Q Le’s most significant artworks; it is the largest installation that the artist has ever made. It represents the culmination of his long fascination with found photographs of anonymous South Vietnamese families taken before the country’s reunification in 1975. Dinh began collecting these photographs after his return to Vietnam during the 1990s, and first began incorporating them into his artworks in 2000. The installation interweaves intensely personal histories with contentious official national histories, exploring the tensions between these. It also considers the role of photography in memory and history. In the artist’s own words: “I thought maybe somehow I’d be able to find my family photographs that we left behind when we escaped from Vietnam, we couldn’t carry [them] with us. So I started collecting them, and I think eventually, they sort of became a surrogate family photo album. […] You know, many of these families didn’t survive the war. Or maybe their family, like my family, escaped Vietnam and they couldn’t carry these photographs with them. So I think that’s why there were so many photographs. […] These images are also special for me because…they’re a very important record of Southern Vietnam. After the Vietnam War ended in 1975, when the Northern communist government took over the South, they systematically tried to erase the history of the South. […] For me, it’s also about small voices that people sort of disregard. I kind of want to give voices to all these people, in a way.” Crossing the Farther Shore takes its overall form from the artist’s memory of living in mosquito nets in makeshift accommodation in a refugee camp. Alongside this evocation of ephemerality, the work also posits the usefulness of artmaking as a means of preserving at-risk visual records of a contentious past. As the artist explains: “I’m trying to protect this documentation because I don’t want them to fall into disuse and disappear. Once it’s…an artwork, hopefully it will be taken care of in the future.”Like many of Dinh’s works, the installation speaks both to Vietnamese publics and to views of the country from abroad. In this way, it reflects the artist’s diasporic life experience as a refugee and returnee. In Dinh’s words: “The world view of Vietnam is pretty much the whole country as a victim of war. Yes, there were wars, but also we continued with our lives as best as we could, and there were happy moments many happy moments, and I want the world to kind of see a different version of Vietnam.”By showing both the front of the photographs and the handwritten inscriptions on their reverse, the installation makes manifest the circulation of these family snapshots, and their status not only as images but also as talismanic objects. This density of both visual and textual material means that the installation invites repeated, lingering examination: it offers an immersive and endlessly rewarding viewing experience.