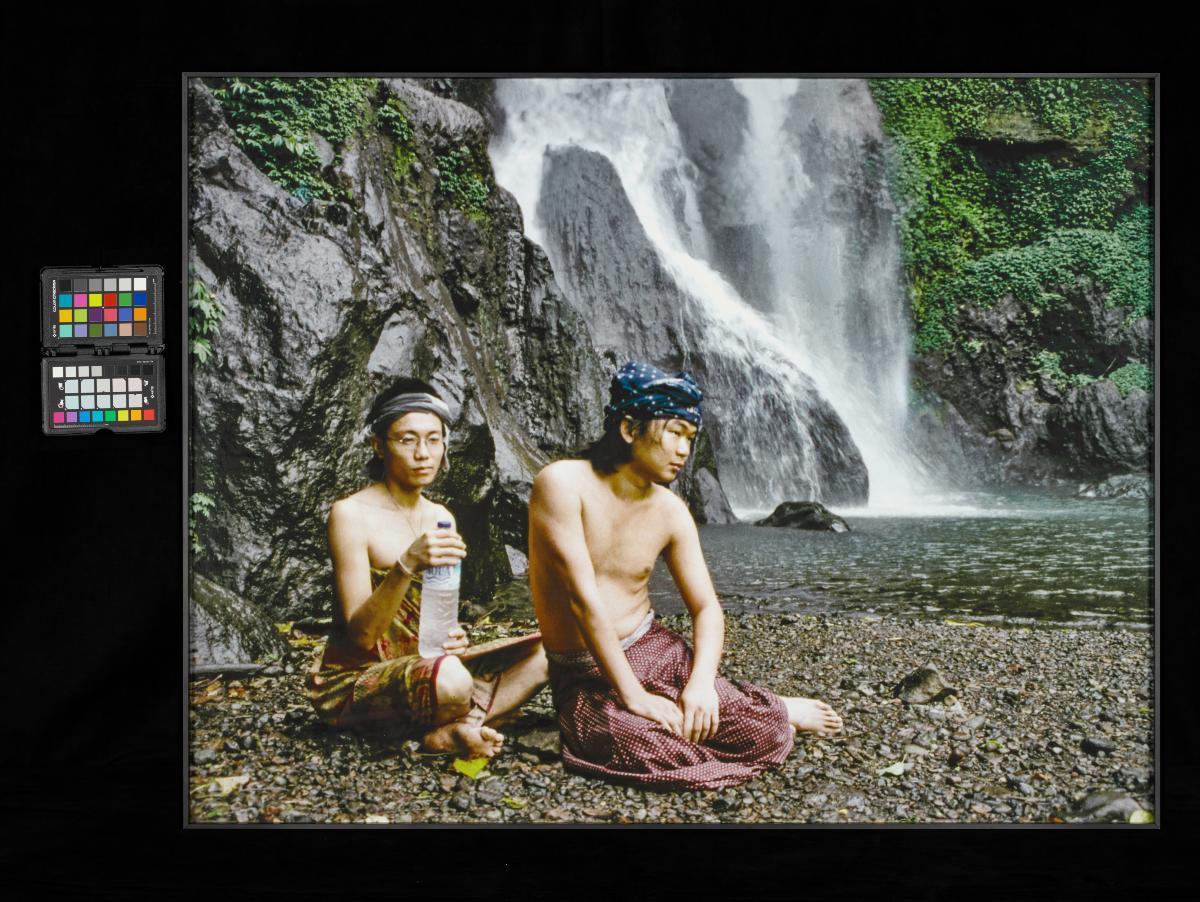

Discussions of modern Singapore’s art history tend to begin with the “Nanyang Style” – a term widely associated with the paintings of a group of Chinese immigrant artists who worked in British Malaya (present-day Singapore and Malaysia) around the 1950s. Four of them in particular occupy a special place in this narrative: they are Chen Chong Swee (1910-1986), Chen Wen Hsi (1906-1991), Cheong Soo Pieng (1917-1983) and Liu Kang (1911-2004), who, inspired by the exuberant paintings of Adrien-Jean Le Mayeur, had embarked on a trip to the tropical island of Bali in 1952 in search of a new visual expression. Enamoured by the rhythms and colours of the exotic tropics, the new cultures they encountered proved catalytic for their artistic development as they began to incorporate elements of Balinese culture into their compositions: the lush landscapes, the communal practices of Balinese inhabitants and elements of the local architecture. The resulting works were displayed a year later in an exhibition titled “Paintings from Bali” at the British Council in Singapore, and garnered critical reception for what was perceived to be an inventive integration of Chinese pictorial traditions and Western aesthetic traditions in the depiction of regional subject matter. The success of the 1952 Bali trip and the ensuing exhibition would prove impactful on the generation that followed, as younger artists were likewise inspired to absorb Southeast Asian material culture into their artistic vocabularies. For subsequent commentators including art historians T.K. Sabapathy and Redza Piyadasa, this excursion southward was viewed to some extent as an originary moment for Singapore modern art. The Nanyang Style’s subsequently swift and unchallenged absorption into the national art historical narrative piqued the interest of a group of young Singaporean Chinese artists from The Artists Village some 49 years later, forming the conceptual backbone of an endeavour they would duly call “The Bali Project”. Almost half a decade after the pioneers’ landmark excursion, the quartet – comprising Jeremy Hiah, Kai Lam, Woon Tien Wei and Agnes Yit (then art students in their twenties) – embarked on a similar journey to Bali in 2001 to uncover the significance of this foreign land in Singapore’s art history, and to discover if they too, with their journey, could attain the same fame and recognition that the pioneers did with theirs.The collective’s shared curiosity and earnestness saw them conducting substantial research prior to their trip, including interviews with T.K. Sabapathy (who had made one of the very first attempts to define Nanyang art in 1979) and Liu Kang himself, who was by then the only surviving member of the pioneer group. Equipped with new knowledge and insights, the group of them headed to Bali with an open mind and allowed spontaneity to guide their artistic approach. They arrived, however, in a Bali that no longer resembled the pastoral and idyllic scenes depicted by the pioneers; the island had since become a popular tourist destination, and the women who once famously went about their days bare-chested were now more conservatively presenting in public. The young artists attempted to retrace as faithfully as they could the sites visited by the pioneers, and in the process interviewed the local inhabitants who expressed interest and amusement at what the young artists had sought out to do.The fruit of this endeavour was a series of photographs of Jeremy Hiah, Kai Lam and Woon Tien Wei approximating the compositions of iconic paintings by the pioneers and their own imaginings of rural life. In “Two by the Waterfall” and “Masks”, Kai Lam and Jeremy Hiah are seen offering their bodies as bare-chested and sarong-clad Balinese women, improvising with found objects to complete the composition. In “The Ferry”, Hiah assumes the position of Chen Wen Hsi’s boatman posing before a “vessel” assembled unpretentiously with cleaning implements. Noteworthy is also “Bathers”, a composite image of the artists and their doppelgangers mirthfully frolicking unclothed in a bathing pool, as an attempt to populate and recreate the public bathing scene portrayed by Liu Kang in 1988. By this juncture of the trip, Agnes Yit had prematurely departed back for Singapore, and as both Wang Ruobing and June Yap would later note in their respective writings, Yit’s absence in the eventual works produced would mirror the absence of a female figure in the pioneer artists’ trip, as Georgette Chen had only arrived in Malaya the following year in 1953. The two Bali trips, undertaken 49 years apart, reflect the attempts of two distinct generations of artists to engage with issues of place, belonging and history. For the pioneer artists, the search for a new visual language rooted in the regional reflected the preoccupation of immigrants to find a sense of identity and belonging in their adopted lands. In contrast, the revisiting of Bali for the younger Singaporean Chinese artists served as a means to make sense of their own cultural roots, to interrogate their inherited histories, and to perform a deconstruction of their own identities. What began as an earnest investigation of Bali as a critical site in Singapore’s art history just as importantly opened up roads to contemplate the formulations of national identity through art, opening up the initial, seemingly monolithic account of Singapore’s cultural history to greater examination and interpretation. While the pioneer artists had embarked on their journey looking for the ‘other’, the young artists have, in this suite of photographs, become the active subjects of their own art history.