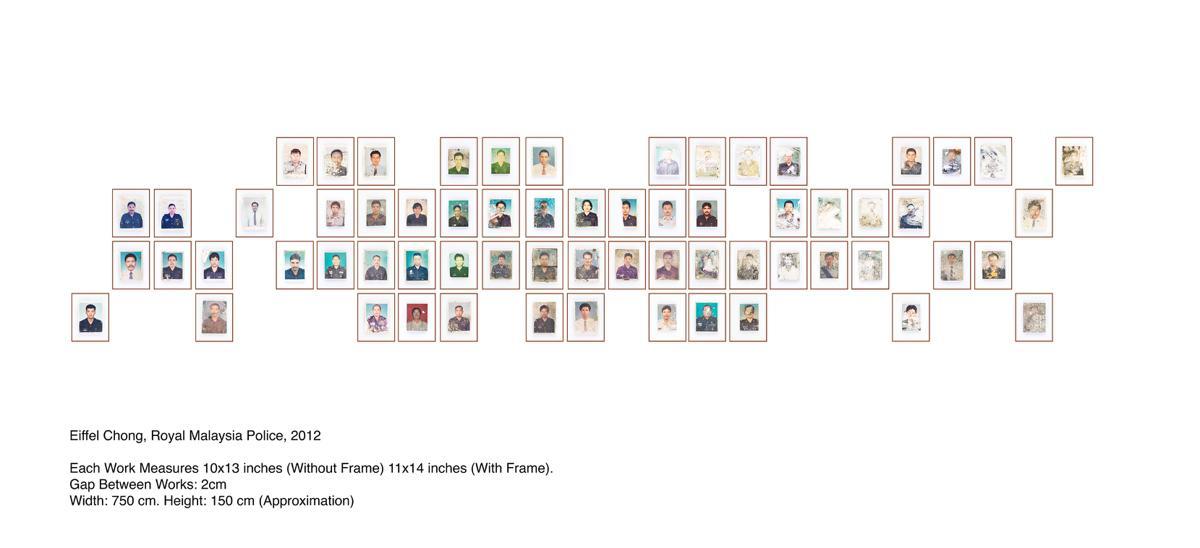

Coming across an abandoned police station in Malaysia, artist Eiffel Chong discovered a number of passport-sized photographs of police officers and booking photographs of criminals. Some had been partially destroyed by dust and the elements, resulting in a mottled appearance blighted by dirt, insects and even mould. After collecting all the images, he re-photographed each one in the studio, treating them as dimensional objects marked by the detritus of time. For the artist, these found photographs came to be a metaphor for the corruptibility of ideals and order as embodied in the law. Preventive laws promulgated into the constitution, which give the police the power to detain suspects without presenting any evidence of wrongdoing before a court of law, is a prerogative that has historically been used to suppress political opposition and civil activism in many countries. Thus, in addition to their law enforcement functions, the police also play a large part in national security, and such power without accountability can, and does lead to the tendency to abuse that very power. In Malaysia, the annual Bersih (the Coalition for Clean and Fair Elections) rallies have been the site of alleged use of excessive force by the police, leading to criticism and probes by independent advisory panels. In Royal Malaysia Police, what is put under investigation is the reliance on the photograph’s power to verify identity – both for the police and the criminal. The artist’s documentary processes testify to the neutrality and material susceptibility of the photograph as witness, evidence and reference.