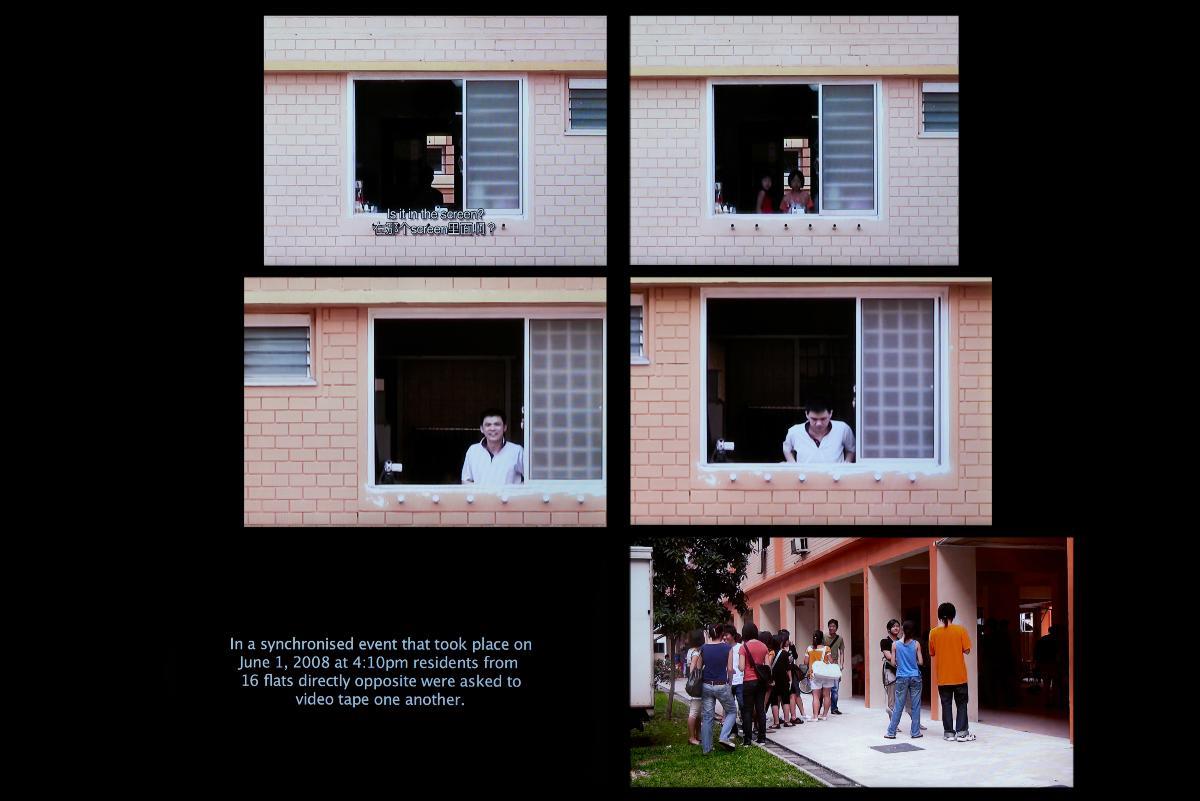

On a Sunday afternoon at 4:10 p.m., 2008, artist Shannon Castleman set up sixteen video cameras in apartment blocks facing one another, on Jurong West Street 81. She asked residents in these buildings to film their neighbours in the apartment directly facing theirs, going about their daily domestic lives (with the agreement of the participants). After filming was completed, residents were invited to share a meal together in the void deck. Castleman describes the project in utopian terms: “It breaks down an invisible barrier between residents, the empty space between them. It allowed Housing Development Board (HDB) residents to view and be viewed … it is an artwork about neighbours discovering neighbours, looking at each other from across a void.” While Jurong West Street 81 looked to rejuvenate a sense of neighbourliness, or the kampong spirit, among city dwellers, what it simultaneously reflects is a dystopian reality – the congested, compressed urban fabric of contemporary Singapore. The work, shown on sixteen different channels, evokes the inescapable voyeurism of HDB living, where the high-density character of public housing estates ensures that simply looking out the window means gazing into someone else’s home. It also alludes to the widespread phenomenon of public surveillance in Singapore today: sites ranging from shopping malls to traffic junctions, from MRT stations to void decks and lift lobbies, are now watched by the electronic eyes of closed-circuit television (CCTV) units in a bid to deter crime and terrorism – a state of affairs so common as to pass unremarked.