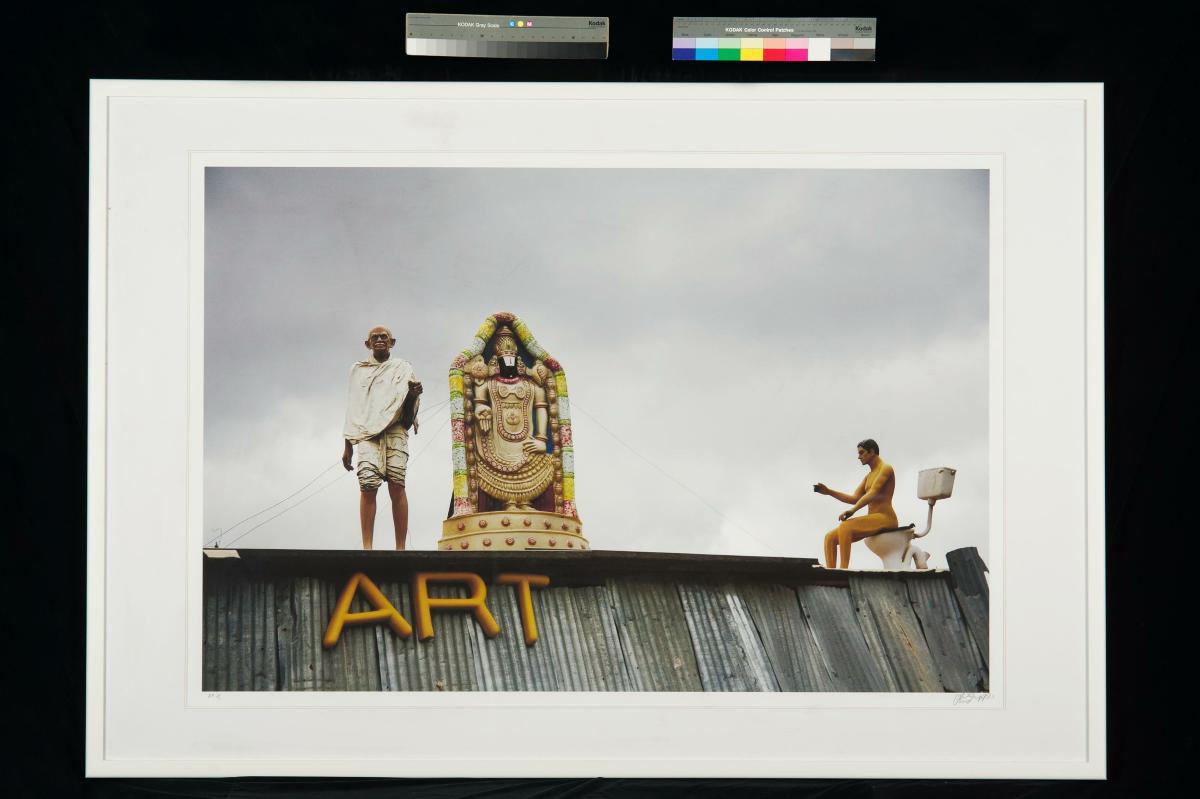

Image size: 95 x 141 cm

Born in Kerala in 1964 and currently based in Bangalore, India. Vilasini was originally trained as a Marine Radio Officer at the All India Marine College in Kochi and only later began studying sculpture from local craftsmen. He has since moved to include new media and photographic techniques in his practice, responding primarily to his local environment while engaging issues that are mostly social and political.(untitled) ART depicts one of those rather odd mix of icons and images that Vilasini found and photographed from the everyday. It contains four major components that are in no manner related to one another but in this curious juxataposition, suggests many possibly spicy and curious stories. In the mix, we find a sculpture of Mahatma Ghandi, an icon of non-violence and founding father of independent India; next to him is a statue of the deity Perumal, popular amongst Tamils from Tamil Nadu state in India and is also known by the name Thirumal, also considered as an incarnation of Lord Vishnu, the ‘preserver’ in the trinity of Brahma – Vishnu – Shiva (creator – preserver – destroyer); on the right is a sculpture of a man, sitting on a toilet in a pose that fondly reminds us of the sculpture of The Thinker (1902) by French master Auguste Rodin. These three sculptures are perched above what seems to be a corrugated metal roof of a shack, emblazoned with a large signpost that spells ART. One could be compelled to infer that these three sculptures are mere advertisements or samples of a sculpture making service by artisans whose studio is the corrugated metal shack below them. Vilasini probably picked up sculpture making as an apprentice in such an artisan’s studio and this ‘found’ image, composed without much conceptual or ‘art’-ful deliberations by its perpetrators, suggests a flashback to Vilasini’s own beginnings as an artist. It also suggests India’s position as a receiver and melting pot of ideologies and influences. The use of such ‘found’ images is common in Visalini’s photographic and art practice and as highlighted in one interview, their appeal began when Vilasini began seeing Kerala, his home state, as a “very peculiar place; people have been coming there from all over the world… and that political ideologies like communism as well as religions like Christianity and Islam have all become intrinsic to the culture of the state.” This clash of icons and potent imageries, which at the same time is indication of the meeting of cultures and ideological influences and also a public and commercial demand for such sculptures is not unique in India but can be found in many parts of the world. In Southeast Asia, it is possible to find similar oddities in artisanal studios in Bali, Bangkok, Hanoi, Jakarta and Manila as artisans hone their craft and receive orders to sustain their ‘art’ business. It proves to show that what we might think as a purely ‘Indian only’ situation might after all be a universal one propelled by the transmigration and acceptance of knowledge, religions and culture, or art.